How to Build a Better Network

A few notes before I jump into this. First, I realized in running through several drafts of this post that it can be hard to talk about networking without coming across as a bit cold or transactional in how one approaches relationships. I hope the note below doesn’t come off that way – my aim was to talk about something that I really care deeply about and offer some ideas for how to strengthen and deepen the working relationships in your life. Secondly, I’d like to thank Patrick (who I reference below) for his review and feedback of several drafts of this post – it was very much appreciated (and needed).

A few notes before I jump into this. First, I realized in running through several drafts of this post that it can be hard to talk about networking without coming across as a bit cold or transactional in how one approaches relationships. I hope the note below doesn’t come off that way – my aim was to talk about something that I really care deeply about and offer some ideas for how to strengthen and deepen the working relationships in your life. Secondly, I’d like to thank Patrick (who I reference below) for his review and feedback of several drafts of this post – it was very much appreciated (and needed).

While we live in a hyper-connected world, how deep do those connections really run? And how do we better cultivate those relationships? It’s easy to pay lip service to our networks, but for me and for many of the readers of this blog our networks – the relationships we maintain with our peers and our contacts – are central to our lives (and here I’m purposely blurring the lines between business and personal, as many of the relationships we maintain do the same). I’m deliberate about how I maintain these relationships and wanted to share some thoughts/ideas on how to better maintain one’s network. I’d like to give credit here to Patrick from MindMaven, who helped me hone these skills and who has been a voice in my ear for the past year keeping me honest about making sure I care and tend to my network.

Make relationship building a priority. I’m often thinking about ways to be more connected to people in ways that are both authentic and meaningful. Relationship building is important to me and rather than let it happen by accident I regularly look for ways to deepen the relationships I have with friends and colleagues. The point I’m making is that being authentic and meaningful doesn’t always have to equate to a lot of work and effort. I actually believe that many people fear the effort they avoid it completely (I’d actually say that most people do). However there are ways in which you can deliver authentic and meaningful experiences to your network that do not cost you too much time and effort.

By making relationship building a priority you will develop habits around it. For example, one important habit I’ve developed is not letting things pass me by that are clear and obvious touch-points with someone I care about. I’ve found that a simple “saw this article about your company and it made me think of you” or “saw your quote here and I found it really insightful” or “saw this on Twitter and thought I’d share it with you” is extremely powerful. Plus it’s authentic. When I see someone I know has raised money, or been featured somewhere, it makes me happy. But instead of letting that thought pass, I take a minute to write a quick email to tell them that. The key here is to not let the moment pass or try to remember to do it later – when you are in the moment, the likelihood of actually doing it is much higher. At the time you see something that reminds you of someone, take 30 seconds and tell them that. It doesn’t take much time to send that message but it shows that you genuinely care about the relationship. The reason why this is so powerful is that it creates interactions that are relevant but where you are not asking for anything. It separates you from the transactional nature of asking for a favor from someone you haven’t talked to in a while. Investing in relationships on an ongoing basis create stronger bonds and if there does come a time when you’re asking something of someone in your network it feels more natural and less transactional.

Tools to help. At the end of the day, tools help but don’t take the place of actual work. In the tech industry we often try to rely on tools as the solution to our challenges when we identify a problem. That is rarely the right answer. Better is to figure out the habits we need to establish and use tools to reinforce or take friction out of those habits. With that as an important preamble to this section, I have found many tools that help me do that…Organizing this activity is important – there’s so much information flowing at each of us, it’s easy to miss stuff. Developing a tool-set to support your networking and engagement work doesn’t have to be particularly complicated – for me it’s Tweetdeck to manage various groups on twitter; Feedly to manage the blogs I read; Accompany to help track news mentions of people in my network; and Contactually, which I describe in more detail below, to organize my network and keep track of who I’m connecting with. They all help me stay on top of what’s going on and allow me to gather data on my network to I don’t have to search out news and updates – those updates come to me.

A personal touch matters. I have terrible handwriting so this doesn’t come easy to me, but I have nice card stock that has my name on it with envelopes with a printed return address and I regularly use this to send notes out to people I’ve met with or who have helped me out in some way. A trick I’ve found is to use a sharpie – it slows me down and forces me to write more clearly (not my strong suit, as I said). The note doesn’t have to be a long one – the point is that I’m taking the time to write something personal, address and stamp it. Emails are great, but I don’t like to miss the chance to send someone a personal note of thanks.

Know your network. Being proactive about your network doesn’t happen by accident but it also doesn’t happen if you’re not deliberate about who is in your network in the first place. Most of us manage this in our heads, which is a mistake. I’ve played around with a few different tools for this and the one I rely the most on is Contactually. This platform integrates with my email and allows me to track how often I’m interacting with my network (over email and twitter at least) and, most importantly, set reminders and goals for how often I want to connect with people in different parts of my network. I’m not a slave to Contactually – I don’t reach out to people for no reason just because Contactually tells me it’s been too long, for example – but I do use it to make sure that I know how frequently I’m interacting with people in my network and to set reminders for myself to stay on top of my contacts.

Ultimately all of this comes down to care and feeding. Your network is in some ways a living, breathing organism. Yet most of us treat it like it’s static and exists when and as we need it. But networks need work and you’ll find you get out of them what you put into them.

Friday Fun #6 – You Had One Job

As internet memes go, You Had One Job is a fun one. There are a few versions running around but the one I pay attention to is the Twitter handle @_youhadonejob1. Full of amusing pictures of things gone a little awry… Happy Friday!

What’s The Optimal Portfolio Strategy for a Venture Fund?

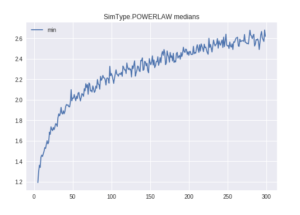

Last year I wrote a few posts (here and here) that talked about how skewed venture returns were. The key take-away graphic from that post is below – outsized returns on venture investments are rare. Much rarer than most people realize.

A key question my post didn’t consider was what the ideal venture portfolio might look like in the face of these data.

Steve Crossan took a stab at modeling the answer to that question using the data from my Outcomes post. It’s an interesting read – you can see his full analysis here. Interestingly, we pondered this exact question at the very start of Foundry Group. Nassim Taleb’s book, The Black Swan had just come out and we decided to read the book and discuss its implications for the venture firm we were about to start in late 2006. I imagine many of you have read the book (if not, I’d highly recommend it) – the basic premise is that humans do a poor job of understanding the likelihood of unusual or improbable events.Black swans are rare but just because you’ve personally never seen one doesn’t mean they don’t exist. Compounding this error, humans are also poor at understanding the causes of these unlikely events after they take place (we misattribute their causes and as a result continue to make poor judgements about their likelihood of reoccurrence).

The robust dinner conversation we had back in 2006 essentially asked the question: “If venture outcomes are Black Swans, what does the optimal venture portfolio construction look like?” Steve asked a similar question in his analysis, which tries to use a simulation model (actually thousands of them) to construct hypothetical portfolios to see what the resulting returns look like. We obviously didn’t have the benefit of the data that my original Outcomes post relied on, but having already been in the venture industry for a while we knew that venture outcomes were relatively rare. In the end, we came to some similar conclusions as Steve did on one end of the portfolio construction scale but our views diverge as the portfolio size gets larger – more on that below.

It’s clear from the data (and from common sense) that every venture firm needs to place enough bets to expose themselves to outsized successful companies. With a small number of investments your chance of a winner is too small and your bets are too concentrated. That’s true no matter the size fund you’re investing (I’m referring to early stage funds here but a version of this is true even for larger, later stage funds; although a higher level of concentration in later stage funds is actually helpful). This is similar to the advice I give to angel investors as well. Diversification is clearly important in venture investing – you can see that from in the graph below from the steep slope on the left side of the graph (which shows on average very poor return multiples for funds that have a small number of portfolio companies).

But is too much diversification a bad thing? Here’s where I think math fails practical reality. Given the rarity of outsized returns (the data from my original post surprised many) a purely theoretical model such as the one Steve ran suggests that the optimal strategy to exposure yourself to outsized outcomes almost has no cap on the number of companies one should invest in (again see the 2nd graph – the slope flattens, but still rising, as the number of companies increases). I think we intuitively understood this back in 2006 and the cruz of our debate centered around just how diversified should a portfolio like ours be. On the one hand there is clearly some benefit to being exposed to a large number of companies. On the other hand it’s not practical to manage that many relationships and we believed there was benefit to knowing which businesses to continue to support and which ones not to. Additionally there is benefit to concentrating ownership in your best performing portfolio companies – something a firm can’t do if it’s spread too thin. It’s a discussion we continued to have throughout the history of Foundry, in our case settling on ~ 30 companies per fund (each of our early stage funds is $232M in size). We felt like that struck the right balance of capacity, ability to concentrate ownership, ability to continue to back “winners” and, frankly, the kind of relationships we wanted to have with our portfolio.

But is too much diversification a bad thing? Here’s where I think math fails practical reality. Given the rarity of outsized returns (the data from my original post surprised many) a purely theoretical model such as the one Steve ran suggests that the optimal strategy to exposure yourself to outsized outcomes almost has no cap on the number of companies one should invest in (again see the 2nd graph – the slope flattens, but still rising, as the number of companies increases). I think we intuitively understood this back in 2006 and the cruz of our debate centered around just how diversified should a portfolio like ours be. On the one hand there is clearly some benefit to being exposed to a large number of companies. On the other hand it’s not practical to manage that many relationships and we believed there was benefit to knowing which businesses to continue to support and which ones not to. Additionally there is benefit to concentrating ownership in your best performing portfolio companies – something a firm can’t do if it’s spread too thin. It’s a discussion we continued to have throughout the history of Foundry, in our case settling on ~ 30 companies per fund (each of our early stage funds is $232M in size). We felt like that struck the right balance of capacity, ability to concentrate ownership, ability to continue to back “winners” and, frankly, the kind of relationships we wanted to have with our portfolio.

That said, I imagine there’s an argument to be made that 30 is still too concentrated for a fund of our size – we debated this vigorously back in 2006 and still talk about optimal portfolio construction regularly. Certainly there are examples of funds like ours that invest in more (or in some cases far more) companies than we do (FirstRound Capital comes to mind as does True Ventures). And, of course, there are many examples of similarly sized funds that have the same or even greater concentration than our model. I’d also note that the earlier stage a fund invests the less concentrated I think it should be – the earlier the investment the larger the distribution of outcomes. And similarly, the smaller a fund is the less concentrated it should be as well – lacking the ability to continue to invest across rounds (and therefore to meaningfully concentrate ownership in clear winners) the more diversified the initial investment set should be.

As a student of venture math, I love these sorts of questions. I’m sure we’ll be debating them for years and years to come.

You May Have Too Many VCs On Your Board

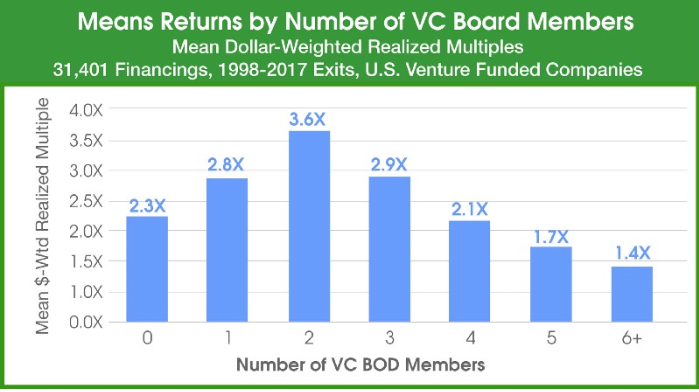

Those that have followed my blog for any period of time know that I love the data that my friends at Correlation Ventures gather and write about (for example the data behind my post Venture Outcomes are Even More Skewed Than You Think or IPO or M&A). Today they released some data on the correlation between the number of venture board members around the boardroom table and the success of venture funded businesses which I thought was pretty illuminating and which confirmed a long held suspicion of mine.

I haven’t counted exactly but I’ve been on dozens and dozens of venture funded boards in the almost 20 years I’ve been a venture investor. Some have been fantastic. Some have been dysfunctional. Most have been somewhere in between. I’ve had the experience of being the sole venture board member. I’ve also been on boards as large as 15 or more when you include not just the board members but also the board observers, associates and others that regularly attend board meetings. I’ve often wondered what the optimal number of venture board members is and have regularly cautioned CEOs and founders against adding too many; and especially adding too many too early in the life of a company.

Today, Correlation answered this question empirically in a fantastic analysis that plots the correlation between the number of VC board members and the ultimate success of a business. They’ve controlled for factors beyond this variable and from their analysis we can draw pretty clear conclusions about how many board members is too many.

There’s plenty to talk about here, but the shape of the graph pretty much tells the story. There’s value to having VCs on your board. In fact, there’s value (or at least a correlation with success) to having multiple VCs on your board. But this value diminishes – and does so rapidly – as you add too many. This certainly matches to my experience. It’s almost always helpful to have a few experienced investment voices around the table. But having too many becomes hard to manage and leads not just to conflicting advice, but I’d suspect to CEOs and management teams spending too much of their time on board management and not enough on the business itself. It’s important to note here that the skew on the right tail of this graph was not due to investment stage (which was my first thought when I saw the graph) – Correlation controlled for that, as well as sector, time period, etc. and found that the correlation holds – companies with more than 3 investor board members performed worse than those with 3 or fewer.

I think it’s important to point out here that, at least in my experience, that having too many VCs around the table is bad for companies even if those VCs are good, helpful, competent people. I say this not just for the benefit of my peers who are reading this and with whom I sit on a board with more than 3 venture investors. I say it because I’m trying to emphasize that different board members bring different skill sets to a company and a board. And while VCs certainly come from many different backgrounds, I think the real issue here is that their skill set and points of view are over quite overlapping. They also tend to have a very loud voice in a board room because, despite being fiduciaries of all shareholders, they also represent typically the largest owners (and funders) of a business. Better boards are more diversified. Actually I said that backwards – more diversified boards are better boards. The research clearly shows this. This is true across all types of diversity (background, experience, gender, race, etc.) and ultimately having too much of a concentration of VCs on your board is a type of lack of diversity that creates poor boardroom dynamics and negatively effects businesses.

Now you have the data. It may be time to have some hard conversations with your investors…

Friday Fun #5 – I have your friend’s phone

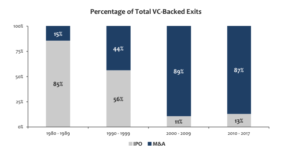

The Changing Venture Market In 3 Images

Want to visualize how the venture funding market is changing? Look no further than these 3 slides (from a presentation put together by our friends at Greenspring). I don’t think much commentary is needed here.

- Average round size at Series A is increasing dramatically.

- Venture is being increasingly driven by large rounds (especially at the later stages – this is significantly skewing the overall funding numbers that are being reported).

- IPOs are the new Unicorns (they’re becoming more scarce than their $1BN valued cousins)

Friday Fun #4: Ordinals, Texas Style

Two of my partners are from Texas (Brad, which surprises many; and Lindel, which surprises no one). This article on the various ways of describing direction in Texas was hallarious. Who knew, “down”, “out”, “over” and “up” were directions…

Two of my partners are from Texas (Brad, which surprises many; and Lindel, which surprises no one). This article on the various ways of describing direction in Texas was hallarious. Who knew, “down”, “out”, “over” and “up” were directions…

What does it mean to be an “executive”

We have active and lively Foundry CEO and Portfolio Executives email lists. They are among the things that I love the most about the community we’re creating at Foundry. I love watching execs across the portfolio (who refer to each other as “Foundry cousins”) help each other out and share ideas. It’s an important reminder that great companies are created not by solo, heroic efforts, but by the collective force of entire communities.

Recently a CEO sent around the following question: what defines an executive (who reports to a CEO)? — especially as different from “a regular manager”. I thought a number of the responses were great and wanted to share them here so they can benefit companies beyond the Foundry portfolio.

What Defines an executive? Especially as different from a manager

The biggest difference is the mental frame you start with when approaching a problem.

A manager starts with their team and their contribution to the problem/solution. “How can marketing do better at X? What’s the impact to marketing? How can I make a business proposal to get marketing more resources to do x”) The manager spends 90% of her time thinking about her team/department/role, and 10% of the time thinking how the whole company needs to move together to reach the next level.

An executive thinks like the CEO first. Their first team is the whole company. They have a deep sense of the market, how the business operates together as a machine. Their particular department (even their role) is the secondary consideration. An executive spends 80% of her time thinking about what we need to accomplish as a company, and how all the teams need to work together to achieve those things, and only 20% of her time thinking about her department/role.

_______________

An Executive:

Finds a way to success. The (functional) buck stops here. Most managers are used to someone above them being accountable and, therefore, not really thinking all that thoroughly through their decisions (or lack of decisions) and their impact. Executives can’t afford that laissez faire approach.

Is a model of delegation. Are very clear on what specific objectives and decisions are being delegated, drives alignment with their colleagues about the principles that underlie those delegated tasks and decisions, gets out of the way and then neutrally assesses outcomes.

Is a model of company culture.

Coaches the coaches. Rather than thinking as much about individual contributors’ tasks and performance, spends much more time coaching their managers on how to be great managers.

Puts company (not function) first. Knows what it will take for the company to win and is constantly in pursuit of that whether in their functional area or as an assist to another. This includes budgets – always aware of when there is a higher-priority expenditure outside their purview.

Challenges the CEO. It’s vital for every CEO to see the icebergs coming. Each exec is a sentry and its their obligation to challenge the CEO to see potential icebergs — 10 or 20 eyes have much more clarity than two.

_______________

Six things:

1. Can they get the right people into the right roles, in every role in their area?

2. Can they put together a plan that supports the objectives of the business, then decompose it and push accountability for achievement of its component parts deep into the organization?

3. Can they establish clear and simple metrics of progress for every single employee?

4. Can they ensure that their business rhythms are set up correctly and that the right conversations are happening?

5. Can they create a culture that supports the priorities and objectives of the business?

6. Can then get everyone in the organization involved in developing the organizational narrative / the company’s understanding of itself?

__________________

And this one which was a bit broader in its answer but I thought really framed what it means to function at various levels inside an organization well.

Jr. Director (C)

They can drive results with little or no supervision and can build the tactical plan. They get stuff done via their team vs. as an individual contributor. They aren’t often focused on the higher-level strategy (the why) or surveying / understanding the market at large. They are focused on the quarter instead of the 3 – 5 year timeframe and their silo. Still requires basic coaching on management, team performance/measurement, team structure, etc. (if managing) May or may not have made their first fire in their history.

Director

D’s fulfill the above + they have opinions on building & measuring the program + creating job descriptions.They take on difficult conversations with the team, and may require some coaching. Still requires support on the plan, but less so — they may need some assistance on getting buy-in / communicating that message. They are thinking somewhat strategically, though need direction on strategic initiatives.

Sr. Director / VP

E’s need less support on building the plan, but still need a clear charter to execute on. They motivate and challenge their team and other teams in powerful ways (if a new candidate, they’ve managed teams of 5+ at any given time). Active contributors to strategic conversations. They make hard decisions and can message them (with little to no support). They require little approval / permission before making a decision.

VP

F’s set the charter, get the buy-in, and champion it across the company — not just entrepreneurial, but they are also visionary. They are a leader and actively take on mentorship of others in and outside of their team. They think at the 30K foot view. They go and figure out the vision for their program, and aren’t afraid to take ownership for it. They aren’t afraid to lose their job — they go to bat for their convictions because of the greater good of the team, and they do it with passion and with a focus on the human. They are thinking strategically about their team among others, not just their own silo — they understand most of the business, can critically evaluate areas outside their expertise, and they understand the external environment (competitors, market, etc.).

VP

All of the above. They are one of the top of their field, an expert and trusted source, as acknowledged by the community of their peers both inside and outside the company. They have a vast range of experiences that make them likely the highest quality person we could have in this role. They likely have an unfair advantage (heavy experience in the industry, personal contacts that can lead to BD deals, etc.) that makes them uniquely suited. They are a unicorn of a hire, and they are a change agent for the business at the 30K foot level.

Friday Fun #4 – Behind the Scenes On Our Latest Video – Bored Meeting

I hope you saw that Foundry released our latest video last week – Bored Meeting. At the time I’m writing this more than 100,000 of you have, which is pretty exciting. Bored Meeting follows on the heels of two prior efforts – I’m a VC and Worst of Times. I’m fortunate to have a really talented partner in Jason Mendelson who writes, performs all the instrumentation for, mixes, edits and produces these songs and videos. It’s a labor of love for all of us – an attempt to bring a little personality and humor to a business that often lacks both.

The process is a blast – from recording the song in Jason’s basement studio to working on costumes to the actual day (or in one case days) of filming. As I hope you can tell from the videos we have a fun time shooting them – often needing to rerecord scenes because we’re laughing too much. Dressing in drag for Worst of Times was particularly amusing, only capped off by Brad leaving Jason’s house in a dress and proceeding to walk about 1 1/2 miles back to our office in Boulder (although perhaps this being Boulder it didn’t turn too many heads…).

With that in mind I thought it would be fun to share a few behind the scenes pictures from these shoots. No one can say we don’t have fun at Foundry!

Focusing on Actions, not Results

I just had a conversation with an entrepreneur I’ve worked with for decades that resulted in an insight that I thought was worth sharing more broadly. We were talking about managing teams and in this case the challenge of getting some of his exec team focused on broader goals and the end result we’re driving for in the upcoming year (a big growth year for this business). The solution we outlined was to focus on actions (concrete, clear, definable) vs. the more vague set of results that we had been trying to align everyone around. We’re still driving to the same outcomes but the leap was too large in a couple of cases for people to get their hands around. By focusing on actions we moved a strategic conversation to a tactical one that each exec could internalize and the end of year results became the outcome not the driver, as they ultimately should be. Every journey starts with a step…