Valuation Policies Are A Mess

Every venture firm reports the “value” of each of its underlying investments. Typically, this is updated quarterly and sent to each of the fund’s investors. The idea is that investors will then have a definitive view of the value of the firm’s investments. Simple, right? But what is the “value” of a private company? Turns out the answer to that question is not so easy to determine, and, as a result, valuation reporting in venture is a mess.

Prior to 2007, most firms held company valuations at the price of the most recent round. This was relatively straightforward and generally pretty consistent across funds. The rationale for this approach was that the best indicator of value was the last “market” price someone was willing to pay for the asset (this approach has some limitations, which I describe below). Under this methodology, GPs did have some discretion to write companies up or down (meaning to say that their value was more or less than the last round

had indicated) due to performance or changing market conditions – especially if the last round was a while ago and the valuation mark was “stale.” Typically the threshold to do this was quite high, meaning that something with the business, the market, or the company’s prospects had to have clearly and materially altered to warrant a change in valuation. While definitely not perfect, this methodology made for relatively uniform reporting (it was uncommon for companies held in different portfolios to be reported at different values – that typically only happened in edge cases with businesses that hadn’t raised in a while, although quite a few funds had policies that held all companies at a maximum of the last round price). There was certainly some incentive for perverse behavior – raising money to establish a new valuation benchmark, or unjustified discretionary mark-ups (say around the time a fund was going out to maket with a new fund), but these were actually relatively uncommon, and most funds only had discretion to write down assets, not write them up.

But there was a concern that this methodology wasn’t rigorous enough and – especially in the wake of the Enron scandal, where the company manipulated its balance sheet by misrepresenting the underlying asset value of various entities it had interests in (among many other things) – there was a desire to make sure that assets of all kinds were valued “accurately.” And some LPs didn’t like that high-performing companies that didn’t have a need to raise capital were “artificially” being held a lower valuation based on their last round price.

Enter FAS 157 (Fair Value Measurements), adopted in the fall of 2006 and enforced for reporting periods after November 15, 2007. The idea behind FAS 157 made a lot of sense: GAAP provided varying methodologies for establishing the fair value of assets and investors and regulators wanted greater consistency and transparency in reporting. FAS 157 (and subsequent modifications) established an “exit value” concept for valuations – basically asking reporting entities and their auditors to establish the price at which an independent 3rd party would purchase an asset. In 2009, FAS 157 was integrated into ASC 820 (Accounting Standards Codification) which classifies assets based on their liquidity (level 1 assets have publicly quoted market prices; level 2 assets aren’t directly quoted but can be relatively easily valued based on market prices; and level 3 assets are those whose value cannot be compared to market prices and which rely on a firm’s internal methodologies for establishing a valuation benchmark). To be clear, FAS 157 and ASC 820 (from here, I’ll start referring to this as ASC 820 as that’s the standard currently in effect) cover many different types of assets – the reporting by venture and other private funds is just one type of asset that is subject to this standard.

However, inside the venture industry, the adoption of ASC 820 caused significant changes in how portfolios were valued. Funds could no longer rely on their existing valuation policies and instead had to establish the “fair value” of each underlying position using varying methodologies approved under the new standard. This was expensive, but more importantly, it caused surprising divergences between how the same asset was reported from one fund to another, depending on the methodology used, the inputs to the valuation model, and the requirements of the audit firm that had to sign off on the fund’s valuations. This only highlighted that company valuations are more art than science. But the accounting standards treated them as the latter and fund LPs required more and more “rigorous” back-up and reporting. All of this, in my view, has made fund reporting less accurate and more subjective, despite its intention to do the opposite. And while valuation reporting used to be more uniform across the venture industry, it has now become much less so.

I recently helped a fund with their valuation policy, and we asked several of their LPs for a “best-in-class” valuation policy. No one could come up with one. The reason is that, under the ASC 820 standard, there doesn’t seem to be one. I understand why LPs want to understand the current value of a portfolio and that they may not have either the technical expertise or access to the right data to go through each of their underlying portfolios and value them in the way they would like. However, in an attempt to create clarity and truth, all we’ve done is obfuscate value even further by introducing more variables, more subjectivity, and more inconsistency into the process. I sincerely believe that most venture firms do their best to come up with a fair value for each asset they own (we certainly do at Foundry) but given the number of variables and the different accepted methodologies for valuing private assets, it’s not surprising that FAS 820 has introduced even more variability and subjectivity into the process.

I know this won’t happen but I wish we would just go back to the simplicity of valuation policies that only allowed mark-ups on price rounds and allowed modest discretion for GPs to write down under-performing assets. This would massively simplify valuation procedures and make them much more uniform. It wouldn’t, in my opinion, materially obscure fund performance. The chaos caused by 157/820 has not been worth it. We’re not closer to reporting the exact “value” of our portfolios…we’re further from it than ever.

The Future of Venture

Just before the end of the year, Erin Griffith of The New York Times published an article titled “What Is Venture Capital Now Anyway?” It’s a provocative look at the state of venture capital and, as these sorts of things are want to do, very quickly started making the round in venture circles as VCs tried to map how they fit into the landscape that Erin describes – a split in how VC firms are operating: some firms are keeping to a smaller, boutique style while a handful are becoming behemoths, almost unrecognizable as venture firms. There’s very little in between.

Just before the end of the year, Erin Griffith of The New York Times published an article titled “What Is Venture Capital Now Anyway?” It’s a provocative look at the state of venture capital and, as these sorts of things are want to do, very quickly started making the round in venture circles as VCs tried to map how they fit into the landscape that Erin describes – a split in how VC firms are operating: some firms are keeping to a smaller, boutique style while a handful are becoming behemoths, almost unrecognizable as venture firms. There’s very little in between.

I think Erin’s description of how our industry is evolving is spot on. But this evolution in the venture market isn’t a surprise. In fact, it’s something I wrote about years ago – back in 2010. In that post, I described the bifurcation of the venture industry and predicted that large, muti-stage, multi-sector firms would continue to raise ever larger funds and that firms with smaller, more focused funds would proliferate at the other side of the market. I described the evolving landscape as increasingly barbelled – predicting that there would be relatively few firms in the middle. At one end of the barbell would be essentially asset managers (asset aggregators) and at the other, smaller firms that were more in the mold of what we historically thought of as venture. The former would be seeking beta and predictable, if lower, returns. The latter would be seeking alpha and greater risk. The middle of the barbell would be sparsely populated and firms inhabiting that space would run the risk of being too large to execute the alpha strategy but too small to be considered true asset aggregators.

I wrote a follow-up piece in 2013, parsing some then-current statistics from the NCVA that backed up what I had predicted in 2010. This trend – as Erin points out – is even more true today. In the 2013 post, I highlighted a few firms that were clearly on their way to the asset management side of the venture barbell. All have subsequently gone on to raise enormous funds: NEA (most recent fund: $6.2B), Norwest ($3B), A16Z ($7.2B), and Khosla ($3B), in particular. But also firms like Greylock ($1B) and CRV ($1B).

I didn’t fully understand the ramifications of the trends when I was first writing about them, but the implications of this continued bifurcation are becoming clearer to me. We often say at Foundry (where we have a fund investment practice and make direct investments) that fund size is fund strategy. That’s always been the case but is even more so now. Fund size has implications for both the kinds of deals your firm pursues, how concentrated your portfolio can be, as well as your approach to valuation and structure (not to mention fundraising – many LPs prefer to be able to write large checks to a small number of firms, something that is putting pressure on fundraising for the smaller end of the market as large firms hoover up a meaningful percentage of LP dollars each year).

I’m not at all saying that large funds are a bad strategy. It’s just a strategy different from what smaller firms at the other end of the barbell are pursuing. And the resources that these firms bring to their portfolio companies make them potentially quite attractive to entrepreneurs (and as co-investors in the right circumstances). But it also means that they have a different risk profile than smaller, earlier-stage investors, which can create misalignment across a cap table (earlier investors wanting to take more risk, asset aggregators looking for more modest risks, and assured returns). All of these firms describe themselves as “venture” but investing from a smaller fund, where returns are driven by a very small number of deals, is very different than investing from a larger fund where (whether you admit it or not), you are trying to put larger dollars to work in any given investment and where the dollar return can be more important than the multiple you generate. Larger firms are also generating a more significant percentage of their pay-outs to GPs from management fees than from carry.

The firms mentioned above who have all raised funds > $1B (in some cases many times that amount) are operating a different business than funds at the smaller end of the spectrum. They aggregate massive amounts of capital across a large and diverse set of funds and often build huge organizations to support their work. One of the key signs that a firm is in the asset aggregation business is not just the size and scope of the organization but specifically the size of its marketing and PR groups. These firms are often quite adept at pushing out materials and content (much of it high quality) to stay front and center in the market – not just among entrepreneurs but, importantly, among LPs. They require meaningful fundraising capacity to keep feeding the asset machine. Their funds are typically consistent performers but are unlikely to generate outsized returns. Importantly, they can accommodate very large LP checks, which many LPs like, and they are a brand name that LPs also feel comfortable with (as I often say, LPs are not in the risk business; they’re in the capital allocation business – which is very different). These firms are chasing something more akin to beta than alpha for the most part, although occasionally they’ll be early into a new market (AI or crypto are examples – especially in the case of AI where early investments required massive checks, which smaller firms were not set up to provide).

On the other side of the spectrum are firms that are true venture firms in the traditional sense. Their funds are smaller, and they tend to raise funds that are similar in size from one fund to the next. They take real swings. They make more of their money on carry than fees. Benchmark is a great example, a firm that Erin Griffith mentions in her article, but many other funds also have this model. Founder Collective may be the quintessential fund of this type (having stayed remarkably true to their mission and fund strategy across many fund cycles), but funds like Union Square Venture also come to mind. Because they’re going after alpha there’s more of a risk of a badly performing fund (and bad vintage) but they’re also more likely as a group to have funds that exceed 3x which is nearly impossible for the asset management funds to do.

More in a future post about the operations of funds at each end of the barbell, as well as some commentary about what happens when you get stuck in the middle. I can understand why Erin’s article made the rounds so quickly. The evolution of the venture market – especially in a cycle of decreasing liquidity and tightening fundraising – is important to track.

Endings and Beginnings

We just made public over on the Foundry blog that our 2022 fund will be our last Foundry fund. I wanted to add a few personal thoughts here.

We just made public over on the Foundry blog that our 2022 fund will be our last Foundry fund. I wanted to add a few personal thoughts here.

When we started Foundry, we were very open about our intention to eventually wind our operations down rather than try to build a generational firm. Over the course of Foundry, we deliberately structured our work in a way that reflected this goal, keeping our organization small and each of the Foundry partners closer to the portfolio (both the companies each of us was responsible for, but also across the portfolio more broadly). We’ve avoided unnecessary silos and kept our focus externally – on companies and our investors – rather than spending time on firm building. For a minute, we flirted with the idea of Foundry continuing (adding more new partners and creating a platform that would outlast us), but as we discussed it more, we ultimately returned to first principles – we focused on investing and supporting our portfolio and not on creating a platform that would outlive us. This is exactly what we envisioned when we started Foundry in 2006, and today marks the public acknowledgment that, with the 2022 fund, we’re ready to stop adding new funds to the mix.

This is something that I’ve personally been thinking about for a while. About a year ago, I started talking publicly about my plan for the 2022 Foundry fund to be my last as a partner at Foundry. I didn’t make a big announcement about it – just started mentioning it in situations where it seemed natural to do so. It felt good to acknowledge it and while I didn’t have a great answer to the obvious next question, I was excited to be able to talk openly about such an important transition in my life. At the time, I wasn’t sure if we would make the same decision for Foundry as a whole, but since I knew my intentions, I thought it would be appropriate to be open about it.

After more discussions internally and careful consideration, we decided that the 2022 fund would be Foundry’s final fund as well. Choosing not to be a legacy firm is one way we’ve challenged norms in the venture industry and just one of many things we take pride in as we reflect back upon our time building Foundry. We’ve loved experimenting with the venture model, whether that was building the first VC AngelList syndicate, investing in markets across the country where venture capital was less prevalent, being among the first GPs to institutionalize a fund investment practice, and attempting to bring transparency, openness (and hopefully some humor) to the venture industry.

We announced our latest fund last May, and we still have plenty of capital to deploy into new companies as well as into the existing portfolio. For now, it doesn’t really change anything in terms of our day-to-day work.

Making a statement like this – that we’re done raising new Foundry funds – is anticlimactic. Venture is a funny business: there’s no day when you pack up your desk, get your gold watch, and leave. So tomorrow will be much like today – we will continue to look at new investment opportunities and work with companies across the Foundry portfolio. I have the same board seats today that I had yesterday. I woke up today focused on my Foundry work, just as I did yesterday and just as I did last week. We raised our last Foundry fund at a fortuitous time, just as the markets cooled off (it’s a great time to be investing), and we have another two years or so of new investments to look forward to. Not to mention a decade or longer of work with the portfolio after that.

I love Foundry and am incredibly proud of the work we’ve done and continue to do. I had no idea in 2006, when we started Foundry Group, what this journey would be like. I was incredibly lucky to be at the right place, at the right time, and with the right partners (who are among my closest friends). We have always prided ourselves on a collaborative work environment and have genuinely supported each other over the past 18 years. At the time we started Foundry, I don’t even think I knew enough to have considered the path that we eventually took (8 funds and over $3Bn in assets, starting a fund of funds, nearly 200 investments, and an honest and transparent approach to venture). It was, and continues to be, an amazing journey. I have a true love for this work, my partners, our portfolio CEOs, LPs, co-investors, and the many others with whom I have the pleasure of working.

The obvious question, I suppose, is “what’s next.” And while that’s a fair question, the truthful answer is: “I’m not entirely sure.” I have a bunch of ideas for how I’ll stay close to startups – my real passion continues to be around engaging with founders. But with a decade or more in front of me working with the companies we support at Foundry and a few years remaining in the investment period for our 2022 fund, I’m more focused on my current work than on what’s next. That said, I have some ideas I’ve been working on in the background that I’m excited to share more about when the time is right. More than what I do, I’ve been thinking a lot about how I do it: how and where I spend my time, along with the elusive dream of having more control over my schedule and the ability to be more fluid and less structured in my work and life.

I’m excited for what comes next…

American Enterprise is In Danger from Recent Court Ruling

This article is cross-posted from The New Builders Dispatch, a publication founded and run by my New Builders co-author, Elizabeth MacBride.

A few weeks ago, the American Alliance for Equal Rights won a legal victory in Atlanta when the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals temporarily blocked a small venture capital fund, Fearless Fund, from running a grant contest that awards $20,000 grants to small businesses led by women of color. The victory may or may not be temporary (this was a temporary stay, not a full adjudication), but the point has been made – there are those like the Alliance who live in fear of a changing world and far too many who support them.

We’ve seen the American Alliance for Equal Rights before: the man behind the Alliance, Edward Blum, brought the successful lawsuits against Harvard University, The University of North Carolina, and The University of Wisconsin that ultimately eliminated race-conscious college admissions programs in the landmark Supreme Court decision, Students for Fair Admissions v. University of NC, et al. But because of the lack of knowledge about how the financing system for small businesses and startups works (or doesn’t) in America, many people may miss the significance of the decision by the three-judge 11th circuit panel. The Alliance is striking a blow at the heart of private enterprise in America.

It’s not the Fearless Fund or the dozens of other interesting experiments in early-stage finance going on across the country that are imposing simplistic race-based thinking on America, it’s the Alliance.

A Profit-Driven Business Model

Fearless Fund, as well as other venture capital funds and accelerator programs, are private enterprises doing what private enterprises (including nonprofits) do: they are serving a fast-growing market for the purpose of making money. In this case, since they are investment companies, they are seeking first and foremost to make returns for their investors. Women and people of color are the fastest-growing groups of entrepreneurs in America. And since the pandemic, people are starting companies at near-record rates. While Fearless Fund is a 501(c)3, it exists to make money for its investors if its management and investment decisions are smart.

It’s not the government’s business, or the legal system’s, to dictate how entrepreneurs or venture capitalists invest their time or money. When the government dictates how capital should be apportioned and to whom, that is the definition of another economic system: Marxist communism.

Not A Zero-Sum Game

In the lawsuit, the Alliances alleges that some of its members – small business owners – were harmed because they could not apply for the Fearless Fund’s grant program. But this betrays a fundamental lack of understanding about how small businesses and financing work. (In reality, we’re sure the Alliance understands perfectly well how all this works).

Unlike college admissions or jobs, funding for startups is not a zero-sum game. A White entrepreneur didn’t get funding because a Black woman did. Indeed, the statistics suggest the system of small business and innovation financing is still working reasonably well for the people it was set up in the 1950s to serve: White men. (Though it could probably work even better). America still remains by far the largest venture capital market in the world.

This system isn’t about perfect fairness: It’s about measured risk-taking based on the unique insights of investors and entrepreneurs working together.

By Their Actions, You Can Judge Them

Venture funds that aim to fund companies led by people of color, or women, or veterans (or any number of other criteria) expand the number of total startups. It only benefits the country if an investor and an entrepreneur make a match that creates jobs, economic energy, and innovation – all of which we need.

The Alliance’s challenge frames the work of venture funds as giving underrepresented groups a boost in their “careers,” probably because the Alliance’s ultimate target is large companies’ workplace policies. But venture funds don’t employ entrepreneurs.

Unfortunately, many journalists covering the case have picked up the Alliance’s framing.

The Alliance purports to support a race-blind society and belongs to a conservative coalition that includes nominal adherents to the idea of free markets. If they were true to this philosophy, they would be working on the two fundamental problems with the financing system for small businesses. First, is that the majority of today’s entrepreneurs are women and people of color.

Fearless Fund and others aren’t set-aside programs. They’re addressing a need in the market that the historically white-dominated system hasn’t moved fast enough to meet. It’s as simple as that – and every dollar an investor feels motivated to risk in the system boosts everyone.

The second, and probably even more important reason, falls squarely in the wheelhouse of people who purport to care about free markets: Changes in the banking sector, including government regulation that helped produce consolidation, have made it unprofitable for banks to lend to small businesses. Government isn’t the enemy, it’s a regulator that can in some cases do more harm than good, as arguably it has in this one.

Twitter-Era Doesn’t Belong in the Real World

The Alliance’s challenge is black-and-white, oversimplified thinking that is more a product of the social media-driven political system than the complicated and nuanced real world. Applying this kind of thinking to the world of messy early-stage finance is potentially deadly. Early-stage finance works precisely because it is messy. Experiments like Fearless Fund have to be given a chance to work – and if they don’t, there’s a great mechanism that will shut them down: It’s called profitability.

The profit-driven business model that the Alliance is attacking is more likely than any other motivation to solve issues surrounding systemic racism in America. Could that be why the Alliance is attacking private enterprise?

SVB and The Tyranny of the Commons

Like many of you, I’ve been reflecting on the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank quite a bit this past week, now that the initial panic has faded into a dulled sense of disbelief. Certainly, there were warnings that SVB was in trouble (most notably from Seeking Alpha – in December – asking if SVB was a blow-up risk and, as if time traveling, describing almost exactly what would come to pass just a few months later). Many others have commented on how and why SVB (and soon after Signature, and nearly First Republic Bank and Credit Suisse) imploded. If you’re interested, I think Matt Levine from Bloomberg has the best overviews of what led to the crisis of last Thursday and Friday (see here, here, and here on SVB; here for an overview of what happend with CSFB, and for those paying close attention, here for what, at the time, we thought was an isolated “crypto thing” in the failure of crypto bank Silvergate, but perhaps was a harbinger for the weeks ahead).

Like many of you, I’ve been reflecting on the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank quite a bit this past week, now that the initial panic has faded into a dulled sense of disbelief. Certainly, there were warnings that SVB was in trouble (most notably from Seeking Alpha – in December – asking if SVB was a blow-up risk and, as if time traveling, describing almost exactly what would come to pass just a few months later). Many others have commented on how and why SVB (and soon after Signature, and nearly First Republic Bank and Credit Suisse) imploded. If you’re interested, I think Matt Levine from Bloomberg has the best overviews of what led to the crisis of last Thursday and Friday (see here, here, and here on SVB; here for an overview of what happend with CSFB, and for those paying close attention, here for what, at the time, we thought was an isolated “crypto thing” in the failure of crypto bank Silvergate, but perhaps was a harbinger for the weeks ahead).

I don’t really feel like rehashing the last week and will let others do that work. But a few things that aren’t being broadly talked about broadly are on my mind. The first, and perhaps most important, is just how important smaller banks are to our economy. Our banking system has become increasingly consolidated over the past few decades – from over 10,000 banks in the mid-90s to barely 4,000 today. Most of this consolidation has come at the expense of smaller community banks and largely, the consolidators have been the country’s biggest banks. So much so that the 4 largest banks controlled over 80% of US deposits before the SVB collapse (and the understandable run to safety that had many depositors opening new accounts at the likes of JP Morgan and BofA has surely increased this number in the past weeks). These larger banks are no doubt important infrastructure in our financial system. But so are smaller banks. As Dina Sherif of MIT and Pia Sawhney of Armory Square Ventures point out in their excellent OpEd in CNBC last week, and as Elizabeth McBride and I discussed in much longer form writing in The New Builders, smaller banks provide critical infrastructure for our entrepreneurial communities – especially women and people of color. SVB itself banked companies across the US and was one of the few banks that would take on smaller venture capital funds (the average venture capital fund size is $56M, according to the NVCA). I personally watched smaller funds struggle to find other options as they scrambled to figure out how to keep their funds operational in the days after the initial SVB scare (most of the funds in Foundry’s partner fund portfolio have less than $100M in assets – a threshold below which larger banks are willing to take them on, especially for the full array of banking products that a fund needs). More broadly, our research for The New Builders showed us just how important smaller banks are to the broader entrepreneurial ecosystem. Simply put, smaller banks do a better job lending money to a wider set of small businesses than the more programmatically run larger banks. Our economy and our finance system needs these smaller banks (also worth keeping in mind that fewer than 1% of companies take in venture capital money; it’s an important part of our economy and drives our innovation economy, but most businesses and most entrepreneurs aren’t seeking venture investment). Our regulatory system must do a better job of understanding this. And the two-tiered system that was put in place by Dodd-Frank, where some banks were deemed too big to fail and were “globally systematically important (G-SIB),” while most were not, isn’t working. Relieving smaller banks from the same reporting and other burdens of larger institutions makes sense (and, as we pointed out in our discussion on this topic in TNB, regulatory overhead is one of the factors driving bank consolidation), but doing so in a way that creates certainty around a small number of huge financial institutions and uncertainty around thousands of others, creates instability across the system. We witnessed that firsthand in the past week as smaller banks faced meaningful runs on deposits as people fled to the safety (and government guarantee) of the country’s largest banks. In an odd nod to the importance of smaller banks, we even witnessed larger banks stepping in to prop up First Republic Bank, which continues to be at risk of failing (I’m sure this was driven by a directive from the FDIC or similar government action, but still notable). There are some clear policy implications here, but that’s a topic for another post, I think…

Also on my mind as I contemplated the past 10 days of craziness was what William Forster Lloyd described as the “Tragedy of the Commons” (the tendency for groups of individuals to act in their own best interest at the expense of the greater good). A bank run certainly fits the bill, as we all witnessed. While it is clear that SVB needed a capital infusion (and that they handled their attempt at raising capital – and specifically the timing and content of announcing that capital raise – extremely poorly), it was the behavior of their depositors that caused the collapse of SVB (and Signature Bank for that matter). If you’re SVB, this is perhaps better described as the Tyranny rather than the Tragedy of the Commons. If the group of depositors had acted in the interest of the whole, the demise of SVB would likely have been averted. It’s hard to say exactly what caused the bank run at SVB – plenty of chatter points fingers at certain venture funds issuing directives to their portfolio companies on Wednesday night and Thursday morning to remove funds from the bank. How much of that is true and how much that was the catalyst for, or just a symptom of, a larger run on the bank is hard to say. But it brought something to mind that I suppose I always knew was the case, but perhaps was wishfully thinking was not so.

It turns out that the Tragedy of the Commons often doesn’t hold for many communities that have shared values and connections. Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to win the Nobel Prize for Economics, is best known for her ideas in this area. Living through the Great Depression, she witnessed the way her community banded together to survive. This informed her ideas, but also her approach to her subject – preferring to be in the field and in the trenches rather than observing from afar. This makes her theories all the more meaningful; she observed them firsthand, almost in the style of an anthropologist vs a traditional economist. Her real-world observation that The Tragedy of the Commons is naturally overcome through the shared efforts of communities. We wrote about Ostrom and her work in TNB and I had this in mind as I listened to pundits describe the SVB (and Signature, and FRB, and CSFB) bank runs as a Tragedy of the Commons. I think of the venture community as a relatively small and interwoven group with, if not shared values, at least overlapping ones. And while some VCs were calling for calm, the community as a whole acted in a panic, in what could have been a calamity for the entire industry (imagine a world for a moment where the Fed didn’t step in to secure depositors; even companies that got their money out of SVB would have been impacted by the collapse in the venture market that would have certainly followed that many companies and funds losing significant funds). This isn’t an indictment of the venture industry or any individual company or CEO who took money out of SVB in the lead-up to the meltdown. It’s hard to judge individual actions in that way. But it is important to look at our industry as a whole and ask why, in a world so interconnected, so tied together, and with communication so fast, that so many acted in their own (perceived) self-interest vs what was an equally clear path to collective action (or inaction, in this case). If you had asked me two weeks ago, I would have said I thought we would have done better. But perhaps my optimism was just naivety.

Techstars Foundation and EforAll

EforAll is a community organization that helps under-represented individuals successfully start and grow their businesses through business training, mentorship, and an extensive support network. If you’ve read my book, The New Builders, you likely know quite a bit about them (and my fondness for what they’re doing). Our systems to support diverse entrepreneurs are lagging, which is why EforAll plays such a critical role in helping foster the next generation of entrepreneurs in our community – taking both a broad view of entrepreneurship and long view for creating impact. They’ve worked with hundreds of companies across the US and continue to expand their reach and the markets in which they are working. I’m both grateful for the work they do and heartened by the stories of their program participants. It’s truly inspiring.

EforAll is a community organization that helps under-represented individuals successfully start and grow their businesses through business training, mentorship, and an extensive support network. If you’ve read my book, The New Builders, you likely know quite a bit about them (and my fondness for what they’re doing). Our systems to support diverse entrepreneurs are lagging, which is why EforAll plays such a critical role in helping foster the next generation of entrepreneurs in our community – taking both a broad view of entrepreneurship and long view for creating impact. They’ve worked with hundreds of companies across the US and continue to expand their reach and the markets in which they are working. I’m both grateful for the work they do and heartened by the stories of their program participants. It’s truly inspiring.

A few weeks ago, the Techstars Foundation announced that EforAll Longmont is joining its Accelerate Equity program, which will give it access to important resources and capital from Techstars. Entry into the Accelerate Equity program is a highly competitive process and it speaks to the quality of the EforAll team and the work that they’re doing on the ground to impact entrepreneurs. I’m thrilled to see this validation of EforAll’s work and am excited about the successful businesses that will result from such a natural partnership. Importantly, this means that the Techstars Foundation will match 20% of donations made to EforAll Longmont through September 30th, up to $20,000. Additionally, my wife and I have decided to match the Techstars Foundation grant, which together will unlock $40,000 for EforAll. If you’re interested in donating to this important endeavor, check out the announcement and donation page. This is a wonderful opportunity to support a worthy local organization and to do so in a way that will multiply the effect of your donation. I hope you will check it out and consider this opportunity for impact. I hope you’ll consider supporting them.

Startup Boards Second Edition

While the first edition was great, this second edition is a well-needed and excellent update (it’s been 7 years since the original came out). I had the chance to read an advance copy a few months ago and loved the practical information and important updates to the new version. Startup Boards is a comprehensive guide on creating, growing, and leveraging a board of directors written for CEOs, board members, and people seeking board roles.

The first time many founders see the inside of a board room is when they step in to lead their board. As I wrote in my blog series, Designing the Ideal Board Meeting, boards are often not managed well and as a result, are often under-utilized. Startup Boards looks at the structure, management, and best practices for leveraging a board to get the best from it. The authors have collectively served on hundreds of boards over the past 30 years, attended thousands of board meetings, and encountered more crazy boardroom drama than most. They’ve poured this wealth of knowledge and experience into Startup Boards. Importantly, this new edition emphasizes the importance of independent board members, diversity at the board level, and openness to first-time board members.

In this latest edition of the book you’ll learn about:

- Board fundamentals such as a board’s purpose, legal characteristics, and roles and functions of board members;

- Creating a board including size, composition, roles of investors and independent directors, what to look for in a director, and how to recruit directors;

- Compensating, onboarding, removing directors, and suggestions on building a diverse board;

- Preparing for and running board meetings;

- The board’s role in transactions including selling a company, buying a company, going public, and going out of business;

- Advice for independent and aspiring directors.

Startup Boards draws on stories from board members, startup founders, executives, and investors. Every CEO, board member, investor, or executive interested in creating an active, involved, and engaged board should read this book—and keep it handy for reference. I hope you’ll grab a copy.

Investors Think They’re More Impactful Than They Actually Are

Companies looking to raise money turn to venture capital for a variety of reasons. Top among them is generally access to capital, but often on the list is the hope that raising capital from experienced (and well-networked) investors will have other positive impacts on their business. Certainly from the venture perspective, VCs (Foundry included) pitch themselves to companies, co-investors, and LPs as more than just capital. Indeed, many firms even institutionalize the practice of providing help to portfolio companies through extensive platforms that may include PR, talent, marketing, technical, and other help (sometimes offered for free, sometimes offered ads a pay-for-service, but often at below-market rates for those services). There are venture firms that have dozens of people employed in the service of their portfolios.

But how impactful is all of this according to the people who actually matter – venture-backed CEOs? The answer may surprise you.

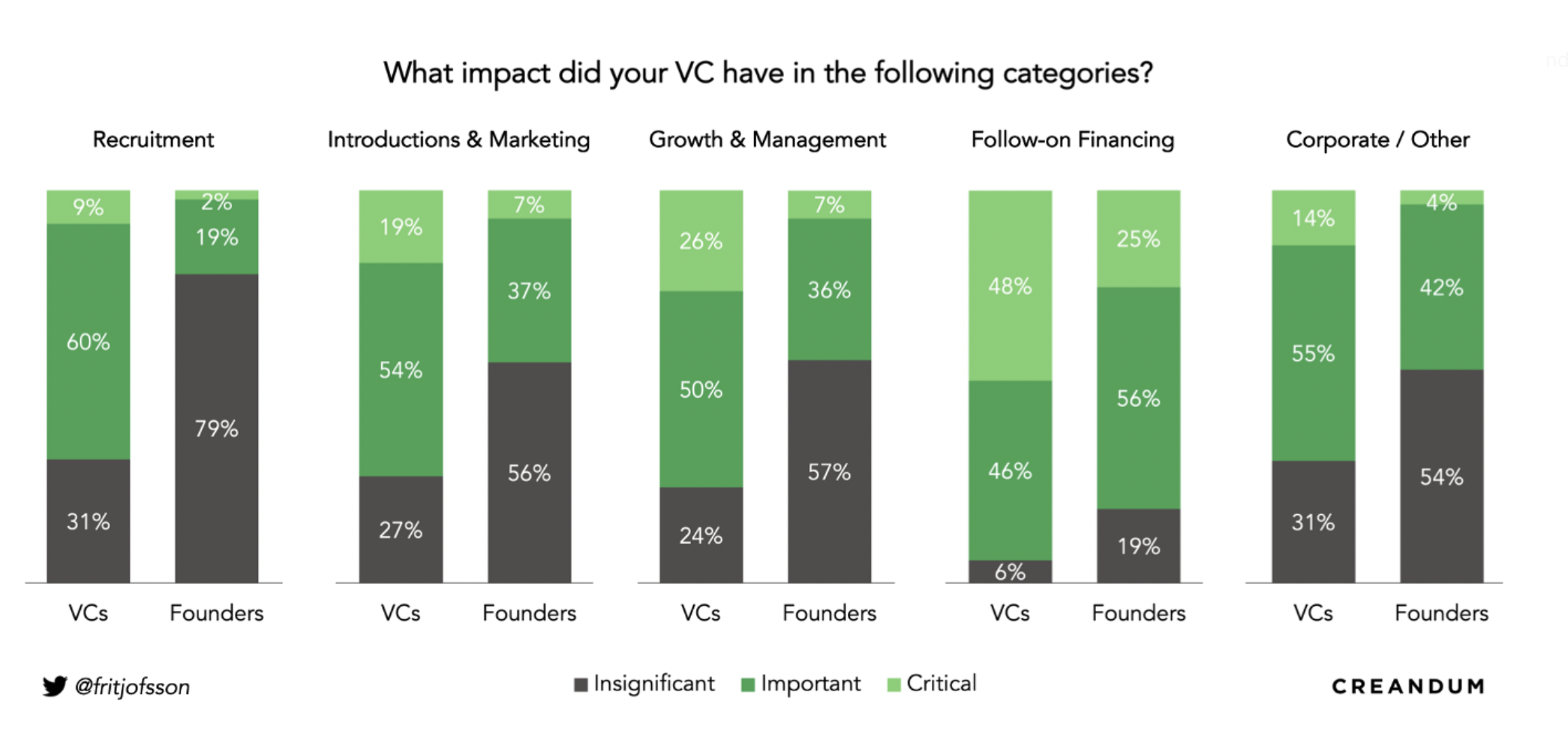

Creandum’s recent article, Do VCs add value? tries to answer this question and, in the process, raises a few other interesting ones. “Most founders don’t feel they are getting value from their investors, even in areas like follow on rounds where they would hope to see specialized experience. They feel they can do better.

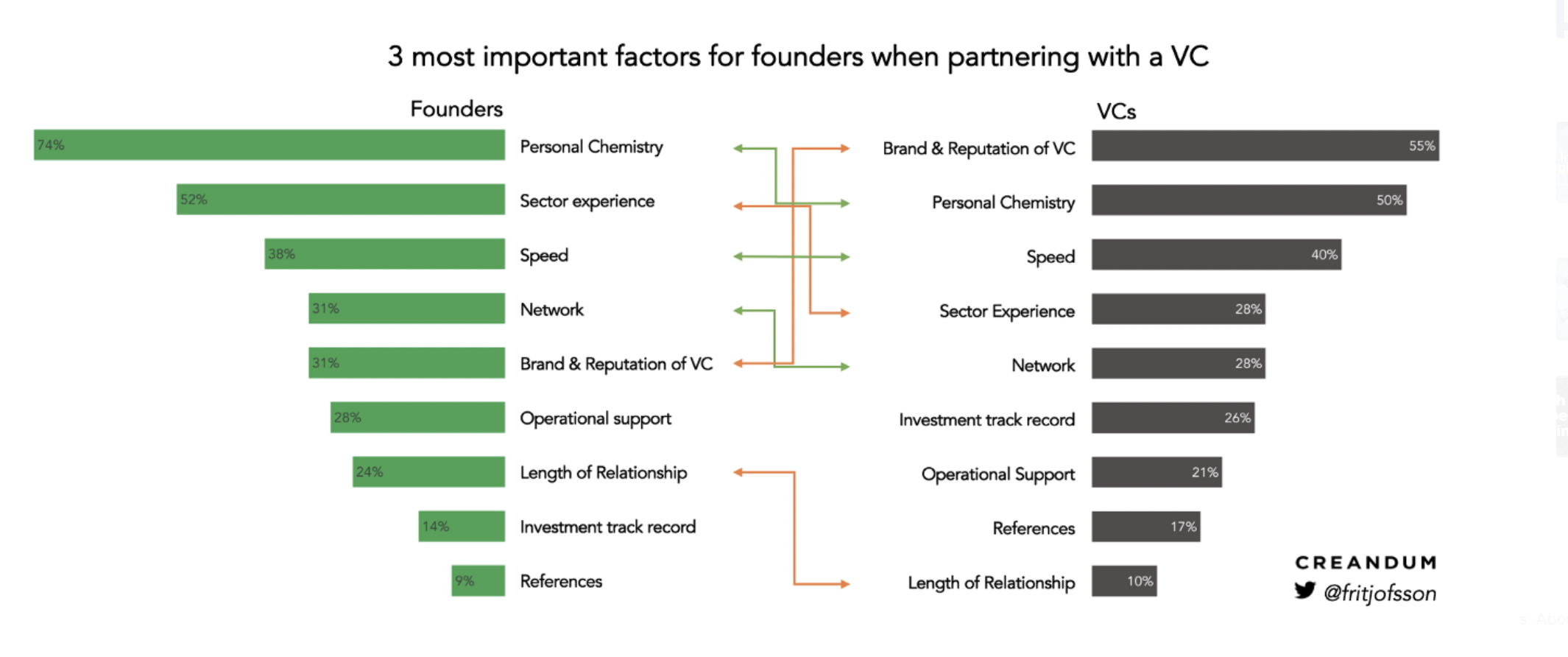

Interestingly, and I suppose not all that surprisingly, VCs have a very different perspective on the value they’re bringing. The two graphs below highlight this across a number of different areas of impact.

I suspect some of this relates to expectation setting and how VC investors “pitch” themselves to prospective portfolio companies. But it certainly highlights the need for a deeper level of conversation between venture investors and their portfolio CEOs about where and how they can truly be helpful. Will they help you find other investors for future investment rounds? How do they make decisions about follow on investments? Do they want to be involved in operations of the business, recruitment of executives, etc? What level of support and expertise will you get from them and their network, particularly when things are rocky?

I suspect some of this relates to expectation setting and how VC investors “pitch” themselves to prospective portfolio companies. But it certainly highlights the need for a deeper level of conversation between venture investors and their portfolio CEOs about where and how they can truly be helpful. Will they help you find other investors for future investment rounds? How do they make decisions about follow on investments? Do they want to be involved in operations of the business, recruitment of executives, etc? What level of support and expertise will you get from them and their network, particularly when things are rocky?

And fascinating to me that VCs believe “brand” is the most important thing that they offer vs where it shows up on the CEO list (#5, behind things like ‘personal chemistry,’ and ‘network’). I wish the survey had broken out “brand” from “reputation” because I suspect the gap around brand alone is actually quite a bit larger (although I don’t think that will stop many firms from focusing on their branding and marketing efforts…). Also standing out from the graphs above is the gap between how much VCs think they’re helping with recruitment vs CEOs ratings of the same (69% of VCs think they’re making a significant contribution to recruiting while 79% of CEOs say that they’re not).

As in most things, focus can help. I suspect investors trying to do too many things for any given company is both unrealistic and in my experience generally not very effective. Pick a few things that you really need help with (they don’t – and shouldn’t – be the same for every investor or board member), clearly outline what help you need and what your expectations are, and focus. Regularly revisit these to track your progress and update your list.

All of this highlights (again) why performing due diligence on potential investors is so important. We’ve just come through a market that was moving extremely quickly (too quickly, in my view). On the venture side, there was plenty to be concerned about in the need to make investment decisions so quickly. Overlooked was the challenge that placed on companies, who were making an equally important decision and entering into long-term relationships without the chance to meaningfully look into the firms that were courting them. Exacerbating this speed were valuations that in many cases were out of touch with reality, putting more pressure early in a company’s relationship with its new financing partners around company performance and trajectory. None of these dynamics allowed companies or their investors to form the basis for a longer-term working relationship. Hopefully, the new market dynamic will allow for more of this.

IRR is a vanity metric

I’m observing that IRR is a metric that is becoming an increasing focus in venture, replacing fund return multiple as the key metric of success. I understand the draw of IRR, and – as a fund draws to a close – there’s no question it’s an important metric. LPs have plenty of options for where to put their money and IRR is an easy way for them to compare how their money grows across various investment options and a convenient way to determine whether they believe they’ve been adequately compensated for the relative risk and varying degrees of liquidity available to them across different asset classes.

I’m observing that IRR is a metric that is becoming an increasing focus in venture, replacing fund return multiple as the key metric of success. I understand the draw of IRR, and – as a fund draws to a close – there’s no question it’s an important metric. LPs have plenty of options for where to put their money and IRR is an easy way for them to compare how their money grows across various investment options and a convenient way to determine whether they believe they’ve been adequately compensated for the relative risk and varying degrees of liquidity available to them across different asset classes.

BUT (and you knew there was a but here given the post title…) it’s a poor way to compare the relative performance of funds early, and even into the mid/later, stages of a fund’s life. But that doesn’t seem to be stopping funds or LPs from touting IRR as the gold standard for evaluating relative fund performance. This is a mistake. Interim IRR is much too easily manipulated and in some cases incents behavior counter to the long-term benefit of LPs (and GPs). A few examples:

- In an up market, IRR values quick capital deployment. Whether we’re in a full correction or not has yet to reveal itself, but for the years leading up to 2022, the market for all things venture was extremely strong. That was great for companies needing to raise increasing amounts of money and fun for investors who often saw companies receive large mark-ups relatively quickly after raising their last round. How many of those valuations will hold remains to be seen, but that kind of market clearly advantaged funds that deployed capital very quickly. Gone was the J-curve (named because often early fund returns are negative – mostly due to fees that drag down NAV prior to initial company write-ups). In markets like this, funds that deploy quickly generate markups on their full portfolio; those that show more patience suffer from an IRR perspective as a larger portion of their fund is yet to be marked up by subsequent financing rounds. IRR doesn’t track this and comparing two funds from the same vintage (fund year) without considering how quickly each deployed capital into an upmarket is a mistake.

- Recycling hurts IRR. Recycling is how funds pay back their management fee and invest the full amount of the fund that they raise (consider a theoretical $100M fund with a 2% management fee for the 5 year investment period and a 1% fee for the tail 5 years; that fund would have to generate $15M of recycling in order to cover the fees that they charge investors). In fact, many funds have the ability to invest more than 100% of their fund size (via profits generated from investments). Traditionally LPs have viewed this as positive. The fund is investing profits, the LP is paying fees on what effectively becomes a smaller fund (in my example above, if the fund invests 110% of the fund, LPs were actually paying a 1.8% management fee). This shrinks the gross/net return spread and is good long-term for LPs (assuming in this analysis that the 10% overage invested returns the same or better than the fund as a whole). But this doesn’t help a fund’s IRR. It actually suppresses it in a similar way that investing over a somewhat longer time period does: by putting capital in the ground later in a fund’s life. Better for the overall return, I’d argue, but not for the interim IRR.

- A lot of things change in 10 years. Most funds have a 10-year life. Really more than that, as 10 years is an increasingly outdated vestige that seems for some reason to live on in fund documents, even if it doesn’t in reality. But in any event, the life of a fund is at least 10 years, and increasingly 15 years or more. A lot changes in that period of time. So if you’re considering IRR at year 3, 4, or 5 – especially for Seed and Series A funds – there are a lot of valuation assumptions that in hindsight will turn out to be completely wrong, but which can drive significant IRR (well, not real IRR, since they never materialize, but interim, paper IRR). For example, I was recently on an update call with a fund and did a quick calculation that over 80% of the gain they were showing came from just 2 companies. Both had raised attractive up rounds. Both were valued at greater than 50x revenue (one was, I think, 70x revenue). This isn’t a commentary on either of these companies – they both may end up being great. But there’s a lot of work for these companies (and many, many like them across the venture landscape) to grow into their paper valuations. If you abstract this across the venture industry or asset class (seed stage venture in this particular case) you run the risk of having a few outlier valuations driving what appears to be spectacular IRR. Some of those companies will be successful. Many will not. We’ll know eventually. But not now. [NOTE: After distributions, the typical capital adjusted duration of even an early stage fund is maybe 8 or 9 years; that’s probably a good benchmark for when you can have a reasonable idea of where IRR will land, but even then there are some large late returns that can change the IRR late in a fund’s life.]

So, food for thought as our industry perhaps becomes overly fixated on a metric that is too easily manipulated (we haven’t even talked about how subjective valuations can be). I’m not saying ignore interim or early fund life IRR. Just take it with a grain of salt. Venture is a long game. And long games take a while to play out.

Money in the Bank vs Burn

With the markets down significantly, financings (at least at the later stages) slowing down, and inflation and interest rates on the rise, perhaps now is a good time to talk about your burn rate. Hopefully, you took advantage of the robust financing markets of the past few years to put some money on your balance sheet. Perhaps you raised at what historically have been very attractive valuations (we certainly have companies in our portfolio that have raised well, well above the historical averages).

With the markets down significantly, financings (at least at the later stages) slowing down, and inflation and interest rates on the rise, perhaps now is a good time to talk about your burn rate. Hopefully, you took advantage of the robust financing markets of the past few years to put some money on your balance sheet. Perhaps you raised at what historically have been very attractive valuations (we certainly have companies in our portfolio that have raised well, well above the historical averages).

With that as the backdrop, it’s probably a good time to remind you that the amount of money you have in the bank doesn’t have to dictate your burn rate. Your underlying business metrics should.

Dividing the amount of money you raised by 18 or 12 months (a general rule of thumb for how soon you’d want to be back in the market) doesn’t necessarily work if you raised a lot, at a high valuation, and still have a few things to work out in your product, go-to-market, etc. Your burn should be based on the unit economics of the business, the fundamental core metrics of the company, taking into consideration your balance sheet and financing prospects. Particularly as companies headed into budget season at the end of last year, it seemed like there was an almost universal temptation to increase burn in 2022. Maybe it’s the rise of the $100M seed round. Or maybe it’s that the venture world seems awash in money (even despite the broader market pull-back). But there seems to be a feeling of free money, perhaps associated with the trend of decoupling of a company’s core, underlying metrics from their proposed burn rate. There are plenty of companies – and we have many in our portfolio – that are well-positioned to increase burn because they have well-established payback metrics along with a strong enough balance sheet and growth rate to support increased spend. But be careful if that’s not you. It’s unclear how far down the financing stack the current pull-back in public markets will reach, but if history is a guide, what starts with a slow-down in late-stage financings will eventually trickle down to Series C, B, A, and beyond. Looking at how companies raised in the past two years is likely not the best indication of your chances of raising money now (or later this year, or even next year). Hopefully, the markets will bounce back some. But don’t bet your business on it. Instead base your burn on your go-to-market readiness, your ability to pay back your marketing and customer acquisition spend, and a reasonable assumption about where your business needs to be in order to raise your next round of capital. Use time and capital to your advantage, accelerating product development as needed, gaining valuable insight on your go-to-market motion. Then, when you’re really ready to hit the gas, use the money that you’ve raised to do that.