SVB and The Tyranny of the Commons

Like many of you, I’ve been reflecting on the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank quite a bit this past week, now that the initial panic has faded into a dulled sense of disbelief. Certainly, there were warnings that SVB was in trouble (most notably from Seeking Alpha – in December – asking if SVB was a blow-up risk and, as if time traveling, describing almost exactly what would come to pass just a few months later). Many others have commented on how and why SVB (and soon after Signature, and nearly First Republic Bank and Credit Suisse) imploded. If you’re interested, I think Matt Levine from Bloomberg has the best overviews of what led to the crisis of last Thursday and Friday (see here, here, and here on SVB; here for an overview of what happend with CSFB, and for those paying close attention, here for what, at the time, we thought was an isolated “crypto thing” in the failure of crypto bank Silvergate, but perhaps was a harbinger for the weeks ahead).

Like many of you, I’ve been reflecting on the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank quite a bit this past week, now that the initial panic has faded into a dulled sense of disbelief. Certainly, there were warnings that SVB was in trouble (most notably from Seeking Alpha – in December – asking if SVB was a blow-up risk and, as if time traveling, describing almost exactly what would come to pass just a few months later). Many others have commented on how and why SVB (and soon after Signature, and nearly First Republic Bank and Credit Suisse) imploded. If you’re interested, I think Matt Levine from Bloomberg has the best overviews of what led to the crisis of last Thursday and Friday (see here, here, and here on SVB; here for an overview of what happend with CSFB, and for those paying close attention, here for what, at the time, we thought was an isolated “crypto thing” in the failure of crypto bank Silvergate, but perhaps was a harbinger for the weeks ahead).

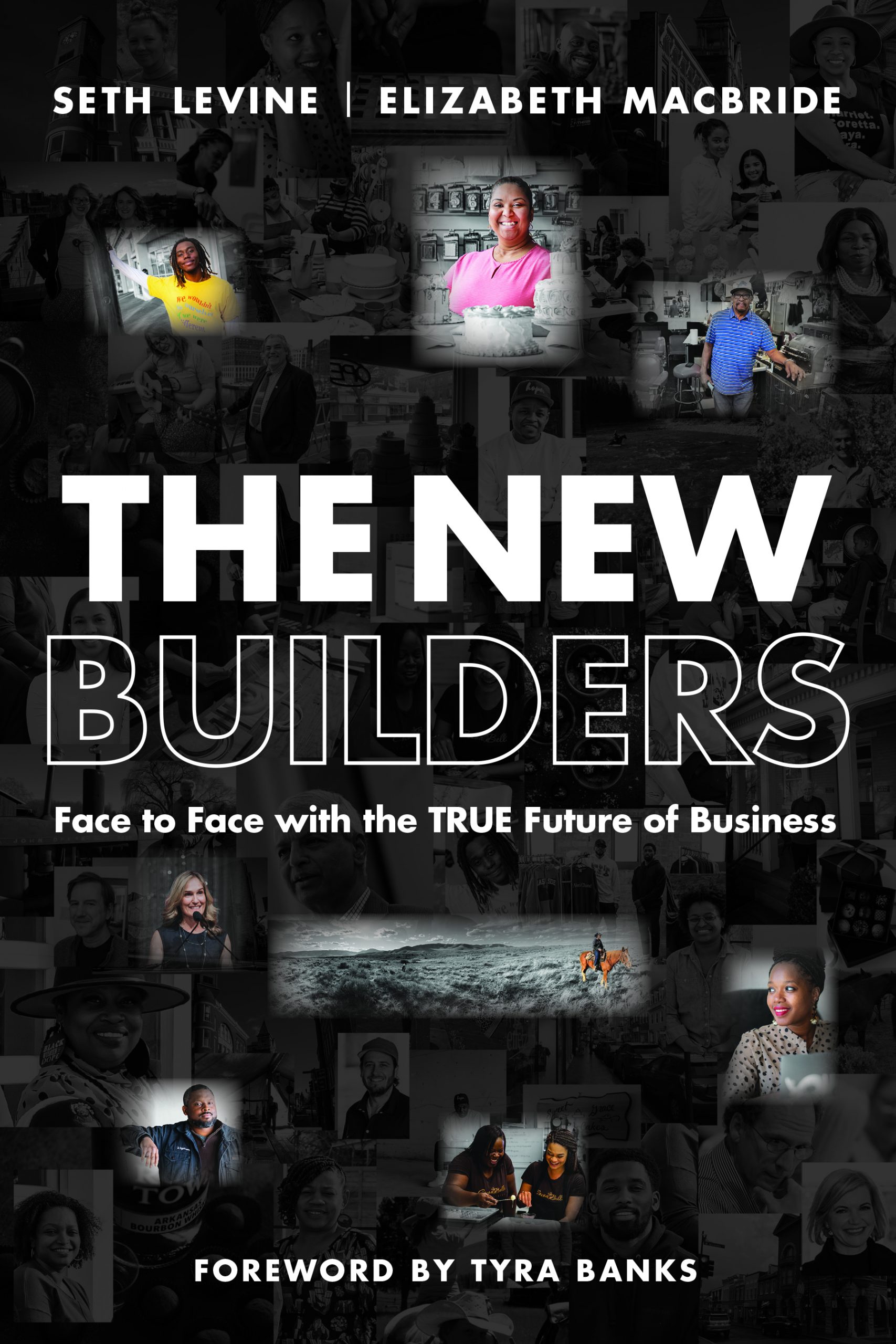

I don’t really feel like rehashing the last week and will let others do that work. But a few things that aren’t being broadly talked about broadly are on my mind. The first, and perhaps most important, is just how important smaller banks are to our economy. Our banking system has become increasingly consolidated over the past few decades – from over 10,000 banks in the mid-90s to barely 4,000 today. Most of this consolidation has come at the expense of smaller community banks and largely, the consolidators have been the country’s biggest banks. So much so that the 4 largest banks controlled over 80% of US deposits before the SVB collapse (and the understandable run to safety that had many depositors opening new accounts at the likes of JP Morgan and BofA has surely increased this number in the past weeks). These larger banks are no doubt important infrastructure in our financial system. But so are smaller banks. As Dina Sherif of MIT and Pia Sawhney of Armory Square Ventures point out in their excellent OpEd in CNBC last week, and as Elizabeth McBride and I discussed in much longer form writing in The New Builders, smaller banks provide critical infrastructure for our entrepreneurial communities – especially women and people of color. SVB itself banked companies across the US and was one of the few banks that would take on smaller venture capital funds (the average venture capital fund size is $56M, according to the NVCA). I personally watched smaller funds struggle to find other options as they scrambled to figure out how to keep their funds operational in the days after the initial SVB scare (most of the funds in Foundry’s partner fund portfolio have less than $100M in assets – a threshold below which larger banks are willing to take them on, especially for the full array of banking products that a fund needs). More broadly, our research for The New Builders showed us just how important smaller banks are to the broader entrepreneurial ecosystem. Simply put, smaller banks do a better job lending money to a wider set of small businesses than the more programmatically run larger banks. Our economy and our finance system needs these smaller banks (also worth keeping in mind that fewer than 1% of companies take in venture capital money; it’s an important part of our economy and drives our innovation economy, but most businesses and most entrepreneurs aren’t seeking venture investment). Our regulatory system must do a better job of understanding this. And the two-tiered system that was put in place by Dodd-Frank, where some banks were deemed too big to fail and were “globally systematically important (G-SIB),” while most were not, isn’t working. Relieving smaller banks from the same reporting and other burdens of larger institutions makes sense (and, as we pointed out in our discussion on this topic in TNB, regulatory overhead is one of the factors driving bank consolidation), but doing so in a way that creates certainty around a small number of huge financial institutions and uncertainty around thousands of others, creates instability across the system. We witnessed that firsthand in the past week as smaller banks faced meaningful runs on deposits as people fled to the safety (and government guarantee) of the country’s largest banks. In an odd nod to the importance of smaller banks, we even witnessed larger banks stepping in to prop up First Republic Bank, which continues to be at risk of failing (I’m sure this was driven by a directive from the FDIC or similar government action, but still notable). There are some clear policy implications here, but that’s a topic for another post, I think…

Also on my mind as I contemplated the past 10 days of craziness was what William Forster Lloyd described as the “Tragedy of the Commons” (the tendency for groups of individuals to act in their own best interest at the expense of the greater good). A bank run certainly fits the bill, as we all witnessed. While it is clear that SVB needed a capital infusion (and that they handled their attempt at raising capital – and specifically the timing and content of announcing that capital raise – extremely poorly), it was the behavior of their depositors that caused the collapse of SVB (and Signature Bank for that matter). If you’re SVB, this is perhaps better described as the Tyranny rather than the Tragedy of the Commons. If the group of depositors had acted in the interest of the whole, the demise of SVB would likely have been averted. It’s hard to say exactly what caused the bank run at SVB – plenty of chatter points fingers at certain venture funds issuing directives to their portfolio companies on Wednesday night and Thursday morning to remove funds from the bank. How much of that is true and how much that was the catalyst for, or just a symptom of, a larger run on the bank is hard to say. But it brought something to mind that I suppose I always knew was the case, but perhaps was wishfully thinking was not so.

It turns out that the Tragedy of the Commons often doesn’t hold for many communities that have shared values and connections. Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to win the Nobel Prize for Economics, is best known for her ideas in this area. Living through the Great Depression, she witnessed the way her community banded together to survive. This informed her ideas, but also her approach to her subject – preferring to be in the field and in the trenches rather than observing from afar. This makes her theories all the more meaningful; she observed them firsthand, almost in the style of an anthropologist vs a traditional economist. Her real-world observation that The Tragedy of the Commons is naturally overcome through the shared efforts of communities. We wrote about Ostrom and her work in TNB and I had this in mind as I listened to pundits describe the SVB (and Signature, and FRB, and CSFB) bank runs as a Tragedy of the Commons. I think of the venture community as a relatively small and interwoven group with, if not shared values, at least overlapping ones. And while some VCs were calling for calm, the community as a whole acted in a panic, in what could have been a calamity for the entire industry (imagine a world for a moment where the Fed didn’t step in to secure depositors; even companies that got their money out of SVB would have been impacted by the collapse in the venture market that would have certainly followed that many companies and funds losing significant funds). This isn’t an indictment of the venture industry or any individual company or CEO who took money out of SVB in the lead-up to the meltdown. It’s hard to judge individual actions in that way. But it is important to look at our industry as a whole and ask why, in a world so interconnected, so tied together, and with communication so fast, that so many acted in their own (perceived) self-interest vs what was an equally clear path to collective action (or inaction, in this case). If you had asked me two weeks ago, I would have said I thought we would have done better. But perhaps my optimism was just naivety.