How much should you be paying your auditor?

With April 15th right behind us, I thought this would be as good a time as any to write about the fun topic of Audit and Tax Prep fees for companies. I know you’ve been waiting for this, so here it goes…

While audits can sometimes feel like overkill for startups (certainly early ones), they’re generally pretty good hygiene. As a practical matter, most lenders will require them, so if debt is a potential part of your cap structure you’ll eventually need one. And most major investors will also require annual audits (we sometimes waive this for seed stage companies, although even then it can make sense). And, of course, if your company is acquired you’ll typically need to provide audited financials to the acquiring company.

First, let’s talk about who is doing the auditing. There are plenty of solid providers out there, including your brothers’ friends’ wife (more on that later) for all sizes and types of companies. Most of our companies start with a firm outside of what’s commonly referred to as the “Big 4” (Deloitte, E&Y, PwC AND KPMG). Most typically companies use a firm from the tier just below that, although we do occasionally have firms use a regional auditor. There’s nothing wrong with that approach, but do keep in mind that as your company grows you may find yourself in the position of outgrowing your firm’s capabilities. In my almost 20 years in venture we’ve seen the big audit firms come in and out (and in again) of the venture stage company market. They’re not set up to compete well on price for smaller companies but when they’re “in” market they’ll discount for a year or two with the hopes that venture companies grow quickly to mid-stage companies and better fit their fee model. When that doesn’t happen there can be some conflicts as the larger audit firms try to push on pricing and/or use more junior staff to save margin. Selecting an audit firm is typically a multi-year commitment (and should be – bouncing around from firm to firm is time consuming, looks like you’re trying to hide something, and creates inconsistencies). In fact, we typically recommend that when you are bidding out audit that you get multi-year pricing to be sure expectations are aligned on both sides.

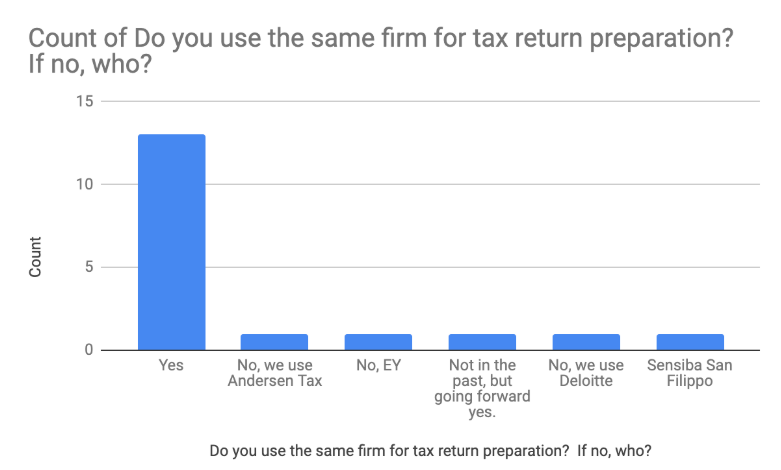

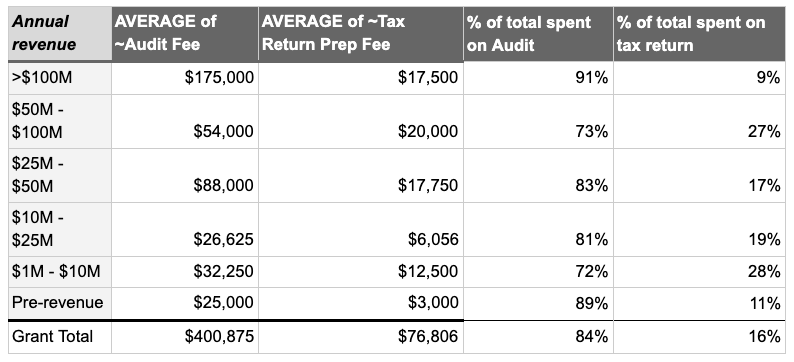

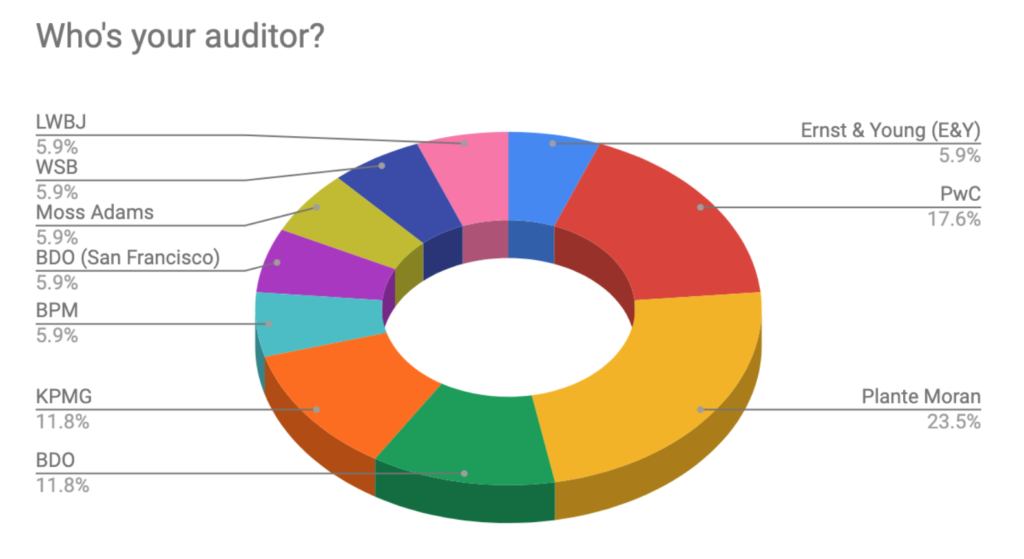

I was curious what fees we were seeing in the portfolio at Foundry so we sent a survey to some of our CFOs to get a sense for what firms they were using and what they were being charged. The charts below are based on those responses (18 in total, so just a sub-set of the portfolio).

You can see what I was describing above. Some of the companies in our survey do you Big 4 audit firms, but the majority use someone from the next tier down.

You can see what I was describing above. Some of the companies in our survey do you Big 4 audit firms, but the majority use someone from the next tier down.

I was a bit surprised by this next chart – the majority of our companies use the same firm for audit and tax prep. There’s convenience to this for startups – especially with limited finance staff – but as you grow it’s more typical to use a different firm for audit and tax.

Here’s the key slide and what led me to the survey in the first place; fees. This generally falls in line with what I expected – there’s an audit floor in the $25k range that’s hard to get much below, but it doesn’t really start scaling until you reach $10M or more in revenue. From there it does scale up, but is dependent on factors such as the complexity of your revenue recognition, the number of jurisdictions you operate in, etc.

With states now paying more attention to nexus and the sales tax landscape post Wayfair, many of our companies are paying more attention to the states in which they file (below we’re talking tax, but there’s also the related question of what states you need to register in; often they’re not the same as there are different thresholds for each). Obviously the graph below is just illustrative that companies are paying attention to this, as w/o knowing the specific businesses in question it’s not possible to say if these numbers are low or high relative to where they should be. But they’ll almost certainly be going up as companies pay more attention to this.

Hopefully these data are directionally interesting and helpful. We’ll plan to run this survey regularly and pull in some more data points.

A-B-E

Almost universally our best companies are constantly experimenting. This takes different forms in different parts of their businesses but the common theme is that every process, every page on your website, every communication to a customer is an opportunity to test and optimize. Sometimes this is chipping away at a mountain (small improvements that add up over time). Other times we see large jumps in efficiency (I had a company recently change some text on a landing page and see a 10% improvement in sign-ups to a white paper). The improvements are important – businesses become efficient over long periods of time and these efficiencies compound each other to create significantly better operational outcomes (and business outcomes). And even small improvements over long periods of time (and when combined with other improvements in the same flow) add up to significant changes. And it’s worth noting that optimization is a never ending process – even when you find something (like the landing page example above) that seems to make a big difference, that doesn’t end the experimenting. Tastes change and effectiveness of pretty much any page/email/process tends to go down over time.

So keep a constant eye towards process improvement and Always Be Experimenting.

How To Get a Job In Venture Capital

One of the most frequent questions I get asked is “how do I get a job in venture?” In fact, I’ve written two posts over the years on this topic – one way back in 2005 and a follow-up to that a few years later in 2008 (the 2nd of the post is the more practical advice if you’re pressed for time; or just keep reading below). A lot has changed in the past 10 years since I wrote my most recent post on this subject. And a lot hasn’t. Below is an updated overview of the venture job landscape as well as some current thoughts on how to break into the industry.

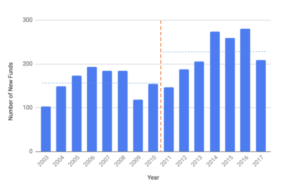

First some stats to outline the landscape. If you’re trying to break into venture the news, in general, is good (the two charts below were pulled from a great post by Eric Feng on the state of the VC market from late last year). The number of new venture firms raising their first fund has increased markedly – especially since 2011 (new funds are a good barometer of the growth of the industry, and a leading indicator of job growth in venture capital).

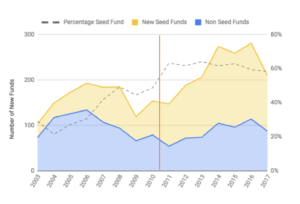

It’s interesting to note that the majority of these new funds are focused on Seed stage investing (not surprising if you follow the market, although investments at the Seed and Seed + stages have started to decline quite a bit from their peak a few years ago).

It’s interesting to note that the majority of these new funds are focused on Seed stage investing (not surprising if you follow the market, although investments at the Seed and Seed + stages have started to decline quite a bit from their peak a few years ago).

So the venture landscape has changed quite a bit since my first post on breaking into venture almost 15 years ago. So has the typical profile of a venture professional. When I first got a job in venture (now we’re going way back – that was 18 years ago) the typical venture analyst had spent 2 years in an investment banking program (maybe, but less likely, a consulting company) and spent a lot of time on the business end of spreadsheets. A venture associate had that same background, had likely worked at a venture firm as an analyst and gone back to business school. Venture principals (VPs, junior partners or other similar titles) were former venture associates who had worked their way up the chain. And partners were former junior partners who had been promoted up as well. Occasionally partners were former successful CEOs who joined the firm that backed them – at the time the most likely way to get into venture w/o having come up the ranks. In fact the hierarchy was so well entrenched, I remember at least one firm when I was applying to be an associate telling me that they’d only consider me for an analyst position because I lacked an MBA (the job I was leaving was running a $55M division of a public company with over 200 people reporting up to me; I had spent the 5 years before that managing teams of various sizes around corporate development, planning, investor relations, etc. But that experience didn’t matter at the time relative to my lack of a business degree. Needless to say, I turned down the offer to interview for that analyst position).

So the venture landscape has changed quite a bit since my first post on breaking into venture almost 15 years ago. So has the typical profile of a venture professional. When I first got a job in venture (now we’re going way back – that was 18 years ago) the typical venture analyst had spent 2 years in an investment banking program (maybe, but less likely, a consulting company) and spent a lot of time on the business end of spreadsheets. A venture associate had that same background, had likely worked at a venture firm as an analyst and gone back to business school. Venture principals (VPs, junior partners or other similar titles) were former venture associates who had worked their way up the chain. And partners were former junior partners who had been promoted up as well. Occasionally partners were former successful CEOs who joined the firm that backed them – at the time the most likely way to get into venture w/o having come up the ranks. In fact the hierarchy was so well entrenched, I remember at least one firm when I was applying to be an associate telling me that they’d only consider me for an analyst position because I lacked an MBA (the job I was leaving was running a $55M division of a public company with over 200 people reporting up to me; I had spent the 5 years before that managing teams of various sizes around corporate development, planning, investor relations, etc. But that experience didn’t matter at the time relative to my lack of a business degree. Needless to say, I turned down the offer to interview for that analyst position).

Today the market is quite different and people from a much wider variety of backgrounds are finding their way into venture. And with more, smaller, seed focused funds, VC firms can be scrappier and more thoughtful about who they want to hire and how and where they find them.

So with that good news, here are a few current thoughts on how to break into venture:

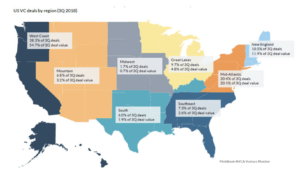

Take the long view. Despite the relative increase in number of venture firms, there still aren’t all that many jobs in venture. And they continue to be concentrated on the coasts to a large extent (see the chart that shows the data from Q3 2018 – generally representative of where the market is at the moment). Embrace that it’s a long shot and enjoy the journey. Which is to say that the things that will prepare you for, and expose you to, a job in venture are things that are generally helpful to you in any career that is focused on entrepreneurship and startups. Not getting a job in venture may be the best thing that happens to your career.

Get involved in your community. Venture and entrepreneurship aren’t spectator sports and are best experienced from within. Most cities now have various local tech meetups, pitch competitions, angel groups, etc. Get out there and participate. If you can, help organize and become a leader in your community (great entrepreneurial ecosystems are inclusive and have many leaders). If you’re interested in startups this should be both fun and easy. Make your presence known and appreciated. Find a gap in your market or someone or something that needs help and get after it. You’ll not only be helping your community, you’ll be making a name for yourself.

Get involved in your community. Venture and entrepreneurship aren’t spectator sports and are best experienced from within. Most cities now have various local tech meetups, pitch competitions, angel groups, etc. Get out there and participate. If you can, help organize and become a leader in your community (great entrepreneurial ecosystems are inclusive and have many leaders). If you’re interested in startups this should be both fun and easy. Make your presence known and appreciated. Find a gap in your market or someone or something that needs help and get after it. You’ll not only be helping your community, you’ll be making a name for yourself.

Get involved in companies. There are lots of great ways to help out companies directly. Hopefully through your work above you’ll be meeting lots of interesting people and companies. Do your best to help them out. Depending on your skill set and level of experience you may be able to offer your services directly to companies (we have plenty of people do this through Techstars for example). Figure out a way to connect interesting people together. Work your network.

Network. Most people are terrible networkers. They treat networking transactionally and they are always looking to take from their networks vs. give to them (good networkers adhere to the #givefirst mentality). Become a better networker and actively work to build out your network – of course including your local venture community as much as you can. This will pay dividends no matter where your career ends up taking you. If you do it well you’ll learn to love it (at least I hope you will). Here are two posts with some basic networking ideas to get you going (here and here).

Engage. Lots of venture capitalists put out a lot of content and it’s never been easier to engage with the venture community. Comment on blog and Medium posts, follow VCs that you respect on Medium and Twitter, send them ideas and thoughts on what they’re writing about and investing in. Stay active and top of mind. There are virtual communities in the comments sections of some venture partner and venture firms blogs. Participate. Personally I have long standing relationships with people who regularly email me with thoughts and ideas that are relevant to Foundry and our investment focus. Like most VCs I’ll take the time to engage and respond to people who are genuine in their outreach and especially those that are trying to be proactive and helpful. My favorite response to people who ask me “what can I do to help you” is to ask them to send me anything they find that’s interesting and piqued their interest (not necessarily venture or startup related). My Pocket reader is full of articles and stories that are sent to me this way. I know many other VCs do the same. It’s a genuine way to start to build relationships.

Look for any way in. Your first job in venture is typically the hardest to get. As more firms are expanding the roles they play with their portfolio, look for different ways in. Many firms now have operational groups that provide services to their portfolio companies. There are a growing number of firms that have someone running “platform” or “engagement” to better connect their portfolio CEOs. More broadly, there are plenty of non-traditional firms out there (not captured in the data above) that are investing either private, foundation or corporate money. In some cities there are organized angel groups that make use of part-time help to make investment decisions. Any job that gets you exposure to making investment decisions or helping those that do will be a good first step into venture.

Work for a startup or start one of your own. This was true 10 years ago and it remains true today. A great path into venture can be to start your own business or work for a startup. It’s a great skill-set to have and will likely put you in contact with the venture world.

Invest if you can. With investment becoming slightly less regulated there are opportunities to put even modest amounts of money to work through platforms like AngelList and others. If you have the ability, it’s not a bad way to show an interest in investing and give you something to talk about in your networking. Obviously this requires at least some amount of capital and I’m not suggesting that it’s a prerequisite to get a job in venture. But if you can do it, it’s a great way to build a mini-portfolio and may lead in unexpected directions.

Persevere. Getting a job in venture is hard and can take a while. Likely it won’t happen. Keep the long game in mind, have fun while you’re going through the process and keep at it. And maybe along the way you’ll end up finding something even more exciting to pursue and forget you ever wanted a job in VC in the first place…

Designing the Ideal Board Meeting – Board Conflict

Designing the Ideal Board Meeting – The Board Meeting

This is the 4th post in my Designing the Ideal Board Meeting series.

I hope this series so far has helped you think a bit differently about how you approach the lead-up to your board meetings. By the time you walk into the meeting you should have a clear agenda that everyone has agreed to, one or two areas of the business that you plan to dive more deeply into, prepared materials that are of a style, length, detail and consistency that efficiently and effectively brings your board up to speed on the business and have been communicating with your board regularly so that there aren’t any big surprises in store for them when they get to the meeting. Here are a few things to consider in setting up the meeting itself:

How long should your meeting run? This is one of the most common questions I get with respect to board meetings. CEOs are obviously sensitive to the time commitment their board (and their team) has made in preparing for and traveling to a board meeting. And as a result they want the meeting to be substantive and feel like the length is sufficient to have justified everyone having come out for it. That’s understandable but to me the key here is quality not quantity. Substantive board meetings aren’t measured by time in the board room and I think a CEO’s first and highest priority should be to create a meeting that is high on substance and information and low on filler. As a general rule for most companies that are reading this something in the 3-4 hour range makes sense for how long your board should be meeting. In my experience meetings that run longer than that (and I’ve been in plenty of 7 hour board meetings over the years) ramble, are not focused, are actually light on substance (much of which gets missed because of all the filler) and tend to devolve into the Exec Team meetings that I warned against in my last post in this series. Less than 3 hours feels too short to cover substantive issues. Obviously there are times when it’s important for a board to meet for a longer period of time. Similarly, as companies grow they often need to add a little time to their board meetings due to the sheer complexity of the business and volume of what needs to be covered.

Include your team. Another common question is whether the exec team (or others) should participate in board meetings. My general view is that it’s positive to have the executive team in the board room. It helps establish a relationship between the team and your board, allows the board to see you in action a bit as a CEO interacting with your team and allows for clear communication back to the team on the board discussion. I’ll talk below about reporting and it’s important to talk to you team ahead of time about what their role is in the board meeting. It’s also important to note that just because an exec is in the room, doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll be asked to give an overview of their functional area. Along the same lines, I generally don’t suggest that teams roll in and out of the meeting and only participate in “their” section of the board discussion. If your team is going to join the meeting they should be there for the full general session (and likely, but not always depending on the topic, participate in the deep dive sessions as well).

Board business first or last? The blunt answer here is that it doesn’t really matter (assuming you can stick to the agenda and time table). Some CEOs (I’d say most) like to get the board business out of the way at the start of the meeting. Some prefer to start with the team in the room for the operational review and reserve the end of the board meeting for board business. The former is nice because you won’t be rushing to approve minutes, option grants, lease approvals or whatever else it is that you need done as “official business.” The latter is nice because there are often other topics that are board business related that you’ll save for the end of the meeting (say an HR or legal issue) that you don’t want to talk about prior to the business update. Keeping to your agenda and time schedule is important here. So is understanding priorities. If you have a messy legal issue you need to talk about and that’s the most important piece of board business, make sure you don’t short-change it by either leaving too little time at the end of your meeting or by letting the business portion of the meeting run long. It’s always better in my view to sacrifice reporting for items that don’t lend themselves well to virtual meetings. Be smart about how you organize your meeting and be sure you have time to cover the most important material. This sounds easy, but I’ve watched it go wrong many, many (many, many, many) times. This typically manifests itself with a CEO wanting every member of their executive team to have air time in the board room, not taking control of the agenda and timing and subsequently letting things run too long thinking they need to cover everything in their board deck vs. prioritizing key items. There are times in a board meeting when the CEO (or board chair if that’s a different person) needs to step in and say “we’re going to have to push the engineering discussion to next meeting; I need us to stick to the schedule.

Discussion item or decision item. If you take nothing else away from this series, I hope you’ll remember this paragraph. Boards are fiduciary bodies and have authority over a number of key decisions made by a company (for a venture backed business many of these are outlined in the company’s governing and investment documents, in fact). BUT the reality is that the vast majority of topics covered in board meetings aren’t ones where the board is making the decision. One of the key functions of a board is to hire and fire the CEO. Most decisions are delegated to the CEO and management team. Boards are not operating bodies – they don’t run your business. In my experience both boards and CEOs consistently mistake the board’s role. You operate your business. If the board isn’t happy with the decisions you’re making they can fire you. But they don’t run the business through you. One way to help you avoid mistaking the board’s role is to be clear from the outset of a topic whether the item you’re talking about is a discussion item or a decision item. Often in a board meeting I’ll stop early in a discussion and ask that question – are you asking us to make a decision here? – in an effort to clarify this. It’s best if you do this from the outset. There are, of course, some items that the board has specific decision making authority over (buying another company, increasing the option pool, signing leases of a certain size, etc.). There are other items that are important enough to the business that you may want to come to a group decision as a board (including you) but where board approval isn’t explicitly required (expanding into a new market, making a critical product decision, etc.). Be clear when you’re asking your board to help you decide something, vs. wanting to have a dicusssion and take input from the board but where the goal isn’t to ceed your decision making authority.

Invite opinions and don’t be afraid of disagreement. Early in my venture career I was on the board of a company run by a CEO who was very command and control oriented. Our early board meetings were reporting heavy and, frankly, pretty boring and generally a waste of time. We finally ended up in a meaningful and heated discussion about product direction debated for about an hour. No conclusion was reached but it was by far the best discussion we had as a board to that point. I stayed after the meeting to debrief with the CEO. He was extremely uncomfortable and told me that it was the “worst board meeting” he had ever had. As we talked, I realized that he had a specific outcome for that conversation he was trying to forcefully guide us to (this wasn’t entirely lost on me in the meeting itself) but more importantly he was totally uncomfortable with the idea of a free form discussion in the meeting (he was also the kind of CEO who called each board member before the meeting so he could have the meeting in advance and control/anticipate the actual meeting itself – something I wrote earlier about not doing). Don’t be that kind of CEO (unsurprisingly, he didn’t last long as CEO of that business). Your board should have opinions. They certainly have different experiences to draw from. Conflict is good and you should seek out board members who won’t be shy with their opinions, who are up for rigorous debate, but who won’t hold grudges if what you ultimately decide isn’t what they advocated for (more on that last point in my next post).

Why, not just what. Going into the board meeting your goal shouldn’t be to simply report what’s happened since your last meeting. It should be to interpret the data you’re showing and describe why the numbers are how they are and what you think that means for the business. This is critical to pass along to your management team as well but was hopefully set up already by the pre-materials you’ve put together where you’ve prepared a board letter (and perhaps your management team has as well) that talks about exactly this question. This is one of the reasons I didn’t like the trend to send around board decks in Google Doc, answer questions in the comments to the doc and then start board meetings with: “does anyone have any further questions about what we sent around?” This is a poor way to ramp into a meeting, doesn’t invite any discussion and absolves you and your team of the important exercise of analyzing and interpreting the company’s progress as part of a group discussion with the board. To be clear, it’s not that all reporting in board meetings is bad. Of course you are going to repeat some key reporting items – to make sure everyone understands the numbers; to highlight a key trend you’re seeing but may not have been obvious; etc. But by focusing on the why you’ll have a much more substantive conversation with your board than if you simply report on the what.

Take a few planned breaks. This should be obvious except that it seems like in many cases it’s not. Include in the agenda specific breaks. For lots of reasons people don’t like to sit in a room for 4 hours straight, focused only on your board discussion. I actually once sat through a 7 hour board meeting with no planned breaks. We were on our own to step out and take a restroom break (presumably offending whomever was talking at the time). It was ridiculous. It’s nice to include these in your agenda so everyone knows they are going to happen, when they’re going to happen, and that the time for them is baked into the agenda. They should be long enough for people to go to the restroom or do a quick check of email, but not so long that you lose flow (5-10 minutes is appropriate here).

Every meeting should have an executive session. It’s helpful to plan time in every meeting to have the non-executive board members meet. 15 minutes is typically sufficient. This is a chance for the board to talk without the CEO or executive team members present. It’s important to have this as part of every meeting – when it’s ad hoc it sends the wrong message to CEOs. After every meeting someone from the board should be tasked with following up with the CEO so there’s feedback from this session every time (which can range from: “sounds like things are going great; we don’t have anything critical to follow up on” to something much more substantive). This last part is key – no CEO should be left without feedback from the closed session.

Take notes on follow-up items. Ok – last item as this post is getting a lot longer than I anticipated. Be sure to take clear notes on any follow-up items that come up in the meeting. Ideally you’d review these just before you step out for executive sesssion and make sure everyone is in agreement as to what they are. These aren’t board minutes – these are your private notes/to-do list post meeting. This will help make sure you actually follow up on what you’ve agreed to, keep your board in the loop on speficic items they’ve asked for more information on and to do so in a thorough and timely manner before you get distracted by the next 100 things that come up in your role running a fast moving business.

Ok – next up will be board meeting conduct: some thoughts on how board members should comport themselves in your meetings and what expectations you should have for their engagement and follow-up.

Designing the Ideal Board Meeting – Your Board Package

This is the 3rd post in my “Designing the Ideal Board Meeting” series.

I didn’t mention this in my prior post but thought of it as I started writing this section on how to put together a good board package. Companies often bias to wanting to hold their board meetings a few weeks after the end of each quarter. The rationale is that this allows the board to review quarterly results. For private companies, I think this is a mistake. For starters, since this is a general bias across the industry you’re fighting for your board member’s time just when everyone else is as well. Not only are these meetings hard to schedule but you’re asking your board members to focus on your business at the same time they’re distracted by being asked to focus on a bunch of other businesses. I also think this is a bad idea because it sets the tone that your board meeting should be focused on reporting. It shouldn’t, as I’ll outline below. Reporting is important but often for startup boards not a very good use of the time you have together. Now – on to the topic at hand, putting together your board package.

So, you’ve been communicating regularly with your board and you’ve sent around and received feedback in advance on your board agenda (both covered extensively in my last post, Designing the Ideal Board Meeting – Before the Meeting). How do you construct a set of board materials that’s informative, insightful and sets the stage for a productive meeting? Here are some thoughts:

Tell me what you think. All good board packages start with some kind of letter from the CEO giving context on the business and what s/he is hoping to cover during the meeting itself. This can be in the email to which the materials are attached, or better yet as a separate letter that accompanies the rest of the board material. This is your chance to tell your board how you’re feeling about the business. What do you want to highlight for them? What things are non-obvious but that you want to be sure aren’t missed? Are there areas you’re struggling with that you’ll be asking the board for help on? How and why did you choose the topic or two that you’ll be doing a deeper dive on in the board meeting? This is always the first thing I read when I receive board materials from a company and, for me, is the most important part of any good board package. Side note: some companies have several of their senior staff write up a similar note to the board. I generally find that helpful, but the key is to guide them away from reporting (it leads to inconsistency and generally is redundant with your other board materials) and towards analysis and interpretation of what they’re seeing in their areas of the business.

Report, but report consistently. The goal of the first portion of your board materials is to report on your business. This will vary a bit from business to business, but the general gist is to highlight the KPIs of the business overall and then have a brief KPI/report from each department or functional area of the company. The key here is consistency. In a later post I’ll share a few examples of the kind of reporting that I find most helpful, but the idea is to develop the outline of a board package that can be updated meeting after meeting. It’s surprising how few companies actually do this and instead start from scratch for each meeting. Not only is it not time efficient for you and your team, it’s hard on your board members – the lack of consistency in reporting makes it hard to compare board meeting to board meeting and hard to find the information you’re looking for meeting after meeting. Keep in mind as well that bullet-point style reporting is an incredibly poor way to convey quantitative information. Your KPIs should cover the key financial and operating metrics (and health) of your business and the department level reporting should include functional level KPIs followed by some bullets that outline key areas for discussion at the meeting.

This isn’t your E-Team meeting. I was on a board once that consistently sent out 160+ page “board decks.” I put board decks in quotes because they really weren’t – they were essentially Executive Team meetings disguised as board meetings. The ensuing board meetings were long, boring, and consisted of the board mostly listening in to the executive team’s discussion about the details of the business (to their credit they changed this after I asked them to consider a different format for the meeting). As the saying goes: “I must apologize. If I had more time I would have written a shorter note.” Long board decks may seem like you’re being transparent but from my perspective it’s just being lazy. Take the time to distill the key aspects of your business so your board can efficiently but effectively understand the business. Your board doesn’t operate your business – they provide oversight and guidance. Help them do that with the materials you provide. I’m not going to give you a page maximum but if you’re more than about 20 or 30 pages for the reporting portion of your board deck, you’re probably too long (see below for “deep dive” topics, which I’m not referring to here).

Publishing in a shared format? I have some boards that publish their board materials in some kinds of shared format for everyone to read together and comment on (typically Google Docs, but sometimes some other shared format). The idea is that the materials are sent out in advance, questions are asked and answered and the board shows up to the board meeting having already accomplished much of the reporting section of the board meeting. This works for some boards, but I have mixed feelings about it. For starters, reporting without context can be challenging (or misleading) and in large part the substance of your board meeting should be about helping provide that context (more on that in my next post). It also has the tendency to lead CEOs to start the board meeting with: “Does anyone have any additional questions that weren’t asked in the shared doc?”, which as we’ll discuss, is not a great way to start a meeting and engage your board. As a practical matter, I’m often reading board materials on a plane where I don’t always have connectivity (and I’m not alone – many of your board members will do this; it’s simply where busy people have large amounts of uninterrupted time). This formate doesn’t lend itself well to off-line.

Deep dives. We’ll talk more specifically about the time allocation of your board meeting itself in the next post in this series, but for the purpose of planning your board materials you should assume that at least half of most board meetings (and generally speaking quite a bit more than that) should be spent on topics other than administrative or reporting. So pick an area or two to take the board more deeply into. Sometimes this is FYI, but often these are areas for feedback and certainly for deeper discussion. These can be event driven – for example discussing an M&A opportunity or an upcoming financing. Or they can be company specific topics, such as a demo of a new product that’s in development or a deep dive into marketing or sales. This is a chance to make sure the board is up to speed on an area of your business that you need feedback on or simply to give them better context about how you’re thinking about the market opportunity or the forward product pipeline. I find this much more helpful than companies that either report for too much of the meeting, do shallow dives into every functional area of the business (to be avoided!) or get bogged down in things that are ultimately unimportant to the company’s future. Be deliberate here – what areas of the business do you want your board to get smarter on? Where do you need some advice or help? And remember this is a collaborative effort. Part of the reason you’re putting out an agenda early and for comment is to make sure everyone is on the same page about what you’re going to go more deeply on in the meeting. Your board can and should offer feedback on this when you send around the proposed agenda.

Just in time doesn’t work for board materials. This is obvious but also seems to be a real challenge for many companies – you need to deliver your board materials well in advance of your board meeting. For most private companies this is about 4 days in advance. It’s absolutely more than 48 hours in advance (many board members, and most VCs, end up lumping several board meetings together over a handful of days in a location – if you don’t get the materials out before people have boarded their flights to come see you shouldn’t expect them to have read the materials). People use to talk about getting materials out a week in advance but that feels like overkill to me. As companies mature, board packages tend to get longer – there’s simply more to report on. Your timing should reflect the depth and quantity of information you’re trying to convey to your board.

Assume everyone has read the materials. If you’re sending your board materials out in advance you should assume (in fact you should explicitly agree as a board) that everyone will come prepared and have read and spent time with the materials. This should be obvious, except it’s clearly not as it’s amazing how often people fly half way across the country for a meeting but haven’t bothered to read the board package. I was in a board meeting once where it was so clear that several of the board members hadn’t read the deck that we actually stopped the meeting and took a 30 minute break so they could. Not coming prepared is disrespectful of the company and of your fellow board members. Don’t be disrespectful.

Ancillary materials. I’ve been referring to “board materials” here as well as “board package” because you should be sending out more than just a board deck/document. We’ve already talked about your CEO letter. But you should also include the most recent month’s financials. These are the financials you’re sending out every month to the board but include them here so everyone has them in a single email. Also include your cap table, any board minutes you’re asking the board to approve as well as option grants and any other board business you’re planning on asking the board to consider in the meeting. I prefer things like the cap table, financials and option grants to be delivered as separate attachments and not in the body of a larger board deck. It makes it much easier to find and make use of them later and to the extent to which some investors are sharing your board materials with their partners it makes it easier for them to strip out the mundane things that don’t need to clog up their partner’s email.

Next up is how to run the meeting itself. We’ll cover how long you should plan on meeting for, the importance of being explicit about discussion topics vs. decision topics, who from your exec team should attend, and more.

Designing the Ideal Board Meeting – Before the Meeting

All good board meetings start well before the meeting itself, so let’s start there for this series on board meetings.

Timing – how frequently should you meet? Most boards plan meetings a year at a time. That makes sense given busy schedules, but leads to the question of when and how often should a board meet. As a good rule of thumb, most startup boards meet quarterly (in fact, most boards of any kind meet about this frequently). This cadence feels appropriate for the level of work that’s involved in putting together board level materials and for a board to perform the appropriate level of governance. There was a time when it was typical for venture boards to meet monthly for a full board meeting, but this frequency – at least in our experience – was too much. Overly burdensome on a company and management and not a very effective or efficient use of everyone’s time. It also reinforced the idea that I touched on in my intro post that the board was an operating body, which it is most certainly now.

Communicating between meetings. Your board meeting shouldn’t be the only way you’re communicating with your board, of course. This varies from company to company but you should certainly be sending around monthly financials (with some discussion/overview thoughts). Many CEOs we work with send out semi-regular updates as well – typically in email format – to keep the board apprised of business operations. Some companies I work with also provide me either access to their management dashboard (KPIs that drive the business) or include me on a daily or weekly automated KPI email that gets sent to the senior team. Others feel that’s too much data and prefer not to. I had one company (since sold) that put me on their automated “won sales” email distribution list so I received an email every time a deal moved into the close/won category (although tbh, this got to be a bit much over time). How much you share of the day to day operations of your business is up to you. We’ll talk later about overall transparency and about not “managing” your board but the general idea between meetings is to generally keep your board apprised of the key things that are going on at the business so they’re better prepared to absorb the more detailed information you share with them for board meetings.

It’s also worth noting that some level of direct communication is helpful here as well. The cadence of that communication varies but you should be in touch with your board regularly so they feel connected to you and connected to your business. Some CEOs like this to be scheduled (a weekly call with their main investors or a regular breakfast or lunch with their board members) but it doesn’t have to be that rigid. And if you need the board’s time between meetings, ask for it. We have many companies that schedule a regular 1 hour operational update between their quarterly board meetings (not full board meetings and where no official board governance business takes place). But always when something comes up that the board should discuss together as a group, don’t be shy about asking for everyone to get together on a call or video.

Setting and communicating the board agenda. Plenty has been written about getting board materials out early and I’ll add my voice to that later in this series, but what’s often missed in these discussions is the importance of setting a board agenda in advance and communicating that agenda ahead of the board meeting and ahead of materials being sent out. This should be done 10 days to 2 weeks in advance of the board meeting. Lay out the agenda and be specific about what topic(s) you’d like to go deeper on with the board. Ask them if there’s anything they’d like to add to the agenda or if there are specific topics they’d like to be sure are covered. Much of the agenda remains the same from meeting to meeting but the meat of your board meeting should vary from meeting to meeting(my next post will include a lof of additional information on the creation of your board materials) . Setting this up in advance and making sure your board is aligned and has input into what key topics will be discussed is important. And should happen well in advance of the meeting.

To call or not to call. Some CEOs like to call each board member ahead of every board meeting. I hate this. For starters it can feel a bit forced and disingenuous. But really I don’t like it because it ends up evolving into a mini board meeting before the board meeting. I think CEOs like to do this because they’re following the “there shouldn’t be any surprises in a board meeting” advice (see below), but if you’re regularly communicating with your board that shouldn’t be an issue. And, importantly, by having a mini board meeting before the board meeting you also lose one of the most powerful benefits of getting everyone together in the first place – talking together as a group vs. getting one-off advice. It’s also pretty inefficient for you as a CEO. If you’re regularly communicating with your board there shouldn’t be a need for 1:1 calls with everyone before each meeting.

No surprises. The benefit of clear, regular communication and setting the agenda publicly and early is that board members shouldn’t be surprised about what’s going on at your business in the board meeting. It’s a cliche not to deliver completely new news in a board setting, but in this case the cliche exists for a reason. Surprising your board in the meeting isn’t an effective way to get good advice from your board. Of course, there are occasionally some issues that require company counsel to be present for the conversation (to preserve privilege) and can’t be specifically spelled out in an agenda or don’t lend themselves to detailed pre-meeting discussion or dissemination. These need items need to be treated differently and you may only be able to communicate that existence of an item that needs to be discussed at the meeting itself. But as a general rule, avoid surprises.

Coming up we’ll stay in the time period before board meetings and talk about the preparation and dissemination of board materials.

Designing the Ideal Board Meeting

This is the first of a multi-part series on Board Meetings. The question of what the ideal board meeting looks like comes up quite a bit in my world and I’m hoping to add my voice to the debate through a few posts (with what I hope will be clear and actionable advice). We’ll cover the creation of a board agenda, the board deck, pre-board communication, how to best run a board meeting, decision topics vs. discussion topics and post meeting follow-up, among other ideas in the coming weeks.

I hope that the reasoning behind designing a good board experience is obvious, but it’s worth stating that getting your board together is expensive. It’s expensive in terms of out of pocket costs – travel, hotels, etc. It’s expensive in terms of time – you and your management team’s time to prepare materials, organize your thoughts and prep for the meeting; your board’s time to prepare for, travel to, and attend your meeting; and everyone who supports that effort’s time to coordinate it all. Given all the costs to get your board together, planning and executing an effective board strategy is critically important.

The opportunity here isn’t just a governance and reporting one – which is how too many companies approach their board work. It’s a chance to constructively and methodically gather your thoughts about your business, get feedback from people not as close to the day-to-day operations of the company as you are, and get feedback on (or in some cases make) key tactical and strategic decisions.

It’s important to remind yourself that a board doesn’t operate your business. You and your management team do that. In fact, we’ll talk in a later post in this series about the mistake many companies make in essentially running too many decisions through their board as a decision making entity and how to best leverage the expertise of your board without outsourcing the management of your business to them. It’s also important to remember that board work isn’t a discrete set of actions that happen only when a board physically gets together. It’s ongoing oversight and help for your business that’s punctuated by those meetings but that actually takes place on an ongoing, rolling basis.

So with that as the preface, let’s jump in….

Resilience

When asked recently if I could describe the attribute that is most important to becoming a successful entrepreneur the word that came to mind was “resilience”. I don’t hear it talked about much in the context of entrepreneurship, but I think it perfectly captures the combination of the ability to bounce back from the adversity, challenge and failure that goes hand in hand with being an entrepreneur while at the same time recognizing and learning from your mistakes. The best entrepreneurs we work with have an uncanny ability to face challenges head on, recognize where they’ve made mistakes, learn from them and move on. That last part is critical – dwelling on your prior mistakes serves no one, slows you down and makes you less likely to trust your future decisions. Great entrepreneurs learn, bounce back and then go on to the next thing.

One parting thought: the truly outstanding entrepreneurs aren’t just resilient themselves, but instill resiliency throughout their organization. It’s one thing for you to move on, it’s entirely another for you to develop a culture in your business where everyone does.

What’s a Fair 409A Discount?

Quick note: I’m not your lawyer. I’m not giving legal advice in this post.

Back in the olden days of venture capital, company boards had wide discretion in pricing company options. As is true today, there was a requirement that options be priced at or above the “fair market value” of the underlying stock (otherwise there would be tax consequences to the optionee and sometimes to the company as well). However the board could determine what that fair market value was and, generally speaking, there wasn’t a practical way that these valuations could be challenged. Most boards did some level of work to determine the FMV of a company’s stock but generally options were priced between 10% and 15% of a company’s then preferred price (because common equity sits behind preferred equity there is typically a discount applied to the FMV of common stock to account for this “overhang”). It was and is imprecise science but – at least in the case of venture backed startups – there wasn’t much harm in an option being priced low. It was a benefit to employees and a slight value transfer from equity holders to option holders (generally speaking in M&A transactions the value of the aggregate option exercise ends up allocated across the rest of the cap table). In a funny way it also benefitted the IRS in terms of tax collections as employees were taxed on the spread between the option and the value of the stock on exit and since these shares were typically exercised at the time of an exit were subject to short term capital gains. Higher strike prices distributes proceeds away from short term gain tax to equity holders who more typically are paying long term gains on the value that was shifted (I’m skipping a huge amount of nuance and detail here but the above is a general representation of how things work).

This all changed on January 1, 2005 when the IRS proposed new rules for the treatment of deferred compensation, including employee stock options (here’s the initial announcement; the code section was finalized in April 2007 – side note, there was a ridiculous interim period when the rules had been proposed but were incomplete and subject to final comment and approval; during that time companies were still expected to comply with the new rules, however the IRS conveniently only gave us until 12/31/05 – almost 18 months before the rules were finalized – to get it all right). Code Section 409A covered a lot of ground related to deferred compensation (and was generally thought to be the result of some of Enron’s business practices, although I think the IRS had in mind a number of different ways companies were structuring deferred comp arrangements that they felt underpriced the market and therefore resulted in immediate – but untaxed – gain to employees).

For startups it meant that for all practical purposes companies would have to hire an outside valuation firm to conduct a 3rd party, arm’s length analysis of the fair market value of a company’s common stock (boards were still free to make their own determination but doing so involved risks that effectively all professional investors determined were too great to take on). Over night a cottage industry was created to conduct these valuations. At the time, the cost of each of these valuations ran between $10,000 and $15,000 annually for each company. These costs have come down a lot since then, and the rules have been tweaked a bit but the overall 409A framework still is as it was when originally adopted – companies must hire a 3rd party to value their stock each year. These reports are generally quite lengthy and not always particularly comprehensible to non-finance professionals. So the rule of thumb is still to consider the FMV of common as a % of the preferred price – at least as a sanity check to the larger valuation exercise.

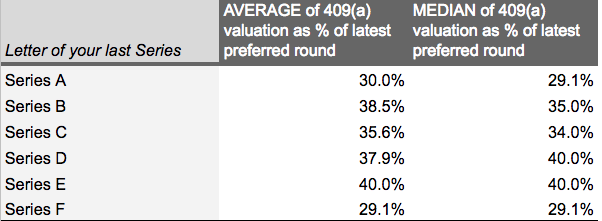

So what should this discount be? I thought it would be worth taking a look at the data across the Foundry portfolio. A number of factors go into the calculation and I assumed that the FMV of common as a % of preferred would vary both by company stage and by the time between the valuation and the last financing round. Specifically I assumed that the longer period of time between a financing and the valuation, the less the gap would be between preferred and common. Similarly I assumed that later stage companies would also show a smaller gap. I was wrong. From the data we collected, there was relatively little variance between company stage or time to last financing and 409A discount to common. There’s a little noise in a few spots in the data (due to small numbers of samples in certain categories) but the numbers were pretty concentrated around the average of 36% of the last preferred round no matter how you slice it. So 30%-40% is the range. Interesting…