3/19/2020 Thoughts

I had a few things on my mind related to the startup environment right now as it relates to Covid-19 and the massive market disruption that we’re in the middle of. It’s a struggle to get them all sorted out in my mind so apologies in advance if these are a little disjointed. As you can imagine we’ve been having conversations all week across the Foundry portfolio (which includes not just companies but also our ~ 35 fund investments; between those we have look-through into a few thousand companies). With that, here are some general observations on the market as well as a few things specific to startup companies (relevant across stages).

We’re still in the quiet before the storm phase. I’m hearing from a lot of companies that this disruption hasn’t affected them. They’re still seeing strong sales pipeline (although this is concentrated in deals later in the pipeline – be careful that you’re watching top of funnel metrics as well). While there are some businesses that have the potential to benefit from our new WFH reality (Zoom is the classic example but we have a handful in the portfolio that fall into this category), the majority I think are simply seeing a brief bounce due to everyone’s schedules freeing up and people having time to actually finish evaluating your product. That’s great, but the truth is that most companies haven’t fully internalized the new economic reality that we’re facing (see more on that below). The result is a brief period of “business at usual, but from home” that is driving some near term sales closes for companies whose longer term prospects aren’t as bright as they may appear once businesses start getting their arms around just how deep an economic downturn we’re likely to be facing. And to be clear, it’s going to be deep.

Companies with direct consumer, travel or related businesses are already seeing the downturn. We have a few companies in the portfolio who have businesses that relate directly to travel (or indirectly to that), people getting together, consumers out shopping, retail and restaurants, etc. These businesses are already seeing a significant impact on their businesses. My point is that they are tip of the spear and are seeing the effects of the downturn first because of the specifics of their businesses. It will ripple down further. Your business needs to plan for that.

We’re about to see the first in a few waves of layoffs. Companies are scenario planning around just how bad this is going to get and many are looking at some level of staffing cuts. These take some time to plan and the reality is that the market has not yet realized just how many people are going to start being laid off (outside of the startup market we’re already seeing this in other businesses). We’re going to start hearing/reading about these layoffs over the next few days and this will accelerate next week.

Prioritize cash preservation over growth. Now is the time to be careful about your cash reserves and spending. Many companies had been leaning into growth – and spending at a very rapid rate to support that. The advice I’m giving most of the companies I work with is to not worry about 2020 growth rate but to focus on preserving cash so we can have the greatest possible optionality when we eventually emerge from this downturn (and we have no real sense right now just how hard things will get). To be clear plenty of companies will grow (some a little, some a lot) through this – but spending ahead of some assumed growth rate right now is a bad idea. Great companies get started in downturns and plenty of great companies that had already been started see their businesses emerge stronger then ever from downturns (both for similar reasons around less competition for resources, better talent available, less expensive marketing, etc.). But you need cash to take advantage of that and now is the time to make those adjustments. Drawing down your debt (as many people have already pointed out) is probably a good idea now as well – you want that cash on your balance sheet (there are some cases where this won’t make sense, which is why I’m avoiding a blanket “you must do this” statement around debt.

Stress test your operating plan. Entrepreneurs are optimists and the temptation is to rationalize how this downturn may actually be good for your business. Most of you will be wrong (either completely or in magnitude). You should be adjusting costs now, full stop. You should have at least 2 other plans that you’ve considered – a zero growth plan and a 25% revenue drop plan. Before you tell me that this isn’t going to happen to your business, just do the analysis and know where you’d stand in these scenarios.

More, not less. I’m sorry to say this, but the reality is that you should be cutting costs more rather than less right now. Whatever your first instinct is, you’re probably off by somewhere between 20% and 50%. Having seeing countless companies go through this (more typically not in such an emergent time), the vast majority of the time companies look back and wish they had adjusted more.

Stock exercise. This is related, but random, but I’m suggesting to the companies I work with to extend option exercise periods extensively for employees that you have to lay off. Most plans require employees to purchase stock within 90 days of leaving (this may vary but 90 days is most common). This feels harsh.

Consider extending COBRA. It’s hard to lay off employees – especially into the job market as it will likely exist over the next few months. And hard to balance being fair to those you’re letting go and preserving cash to continue to operate your business with the employees who are staying at the business. One thing that some companies are doing (and this varies based on capacity and inclination) is trying to offer a few months of paid COBRA for employees they’re letting go.

I just reread this post and it’s more pessimistic than I actually feel. Markets cycle. Even when the disruption is something large and unprecedented like Covid-19. We will get past this. The markets will rebound. Sales will come back. Great companies will emerge. I strongly believe all of that. But I hope the advice above will be helpful to you as you think through navigating the early stages of this crisis and best prepare your business to survive.

Decision making in uncertain times

Making decisions for your business can be hard even in normal circumstances. Right now, in this time of great uncertainty and high emotional stress it’s even harder. I’m on countless calls a day now where I’m trying to talk through with people in our universe (CEOs, GPs of other funds, fellow board members, etc.) critical decisions that in many cases will define the future for the businesses involved. How to react in a time like this is complicated and in most cases is not obvious. Just how bad things may get is unknown, as is how long this will last and what effect that will have on various business sectors and on specifics businesses is unclear. Below are a few thoughts that I’m using to guide my own decision making in this time of crisis.

Making decisions for your business can be hard even in normal circumstances. Right now, in this time of great uncertainty and high emotional stress it’s even harder. I’m on countless calls a day now where I’m trying to talk through with people in our universe (CEOs, GPs of other funds, fellow board members, etc.) critical decisions that in many cases will define the future for the businesses involved. How to react in a time like this is complicated and in most cases is not obvious. Just how bad things may get is unknown, as is how long this will last and what effect that will have on various business sectors and on specifics businesses is unclear. Below are a few thoughts that I’m using to guide my own decision making in this time of crisis.

- Don’t Panic. I say this all the time. 1) Don’t Panic; 2) Gather data; 3) Make informed decisions. The order here is important. This is especially true when times are crazy and there’s even more pressure to make rapid decisions. Take a minute to breath and calm yourself. Think about what data you can gather that will help inform your decision making and what time frame is reasonable to allow yourself to make that decision. Give yourself a little space to collect the information you need to make as informed a decision as you can given the unknowns that will inevitably exist as well as the time frame that’s reasonable for the decision at hand.

- Move quickly but don’t rush. Related and not in opposition to #1, you can still make decisions quickly and decisively, but do so without rushing. When you’re stressed it’s easy to interpret that stress as a need to just get things done. Don’t fall into that trap. You can still move rapidly without rushing.

- Prioritize. When you’re making quick decisions and have a lot of information hitting you at once, it’s tempting to try to just get things off your plate. But that’s a bad way to organize your work even in the best of times. I’m a consistent user of Asana (but you could use Trello, Todoist, Wunderlist, etc) to prioritize my days. It’s especially helpful when things feel out of control to have the framework that a well though through task list provides. Use it to help you prioritize the decisions you need to make that are urgent and to keep track of what’s left to do.

- Be comfortable with ambiguity. One of the most challenging things about making decisions for your business right now is how much we don’t know. That’s disconcerting but you’re just going to have to deal with it. Hopefully your business is well instrumented so at least you’re getting some data in. Take in what you can, recognize that you won’t have perfect information and make the best decisions you can at the time, recognizing that some decisions will need to be revisited when you have more information.

- You can’t control what you can’t control. There’s no sense in focusing on things that are out of your control. So focus in on the things that are within your control.

- Make contingency plans. One of the things that I’m encouraging companies that I work with to do is to engage in some scenario planning. I’ll have a longer post up tomorrow about this but the general idea is to free yourself from pressure in the moment by coming up with multiple plans of action. If we see X we’ll do Y (times a bunch of different scenarios). Your thinking ahead of time will more likely be clearer than in the moment. And you can revisit your thinking over time (before you’ve actually had to implement what you’re working through) and have the benefit of multiple looks at the same set of problems.

Overall I’m seeing high degrees of anxiety and concern about making the “right” decision. That’s understandable given the circumstances. Recognize that no one really knows what’s going to happen here and that your job is to make the best decisions you can. “Right” doesn’t exist in times like these.

Dealing with evolving information about Covid-19

Humans are, as a general rule, poor at changing their minds once they’ve developed a view about something. This can be the cause of plenty of arguments and I suspect is a significant reason we’ve become so much more polarized as a country in recent decades (that, and it’s ancillary effect of causing us to seek out only information and data that support our unbending view).

But in the case of dealing with a pandemic like Covid-19 it can be downright dangerous. I thought it would be helpful – perhaps even important – to talk about why being open to new and evolving information is so critically important in a time when what we know about Covid-19 is changing so rapidly.

I’ve certainly been through this journey myself. My views continue to change as I learn more. An hour ago I posted about the need to dramatically change how our society is approaching the virus and specifically some radical changes that we need to make now to slow the spread of the disease. People reading it will have various world views about the virus, bring varied biases about just how severe it is and as a result what we should do about it. I’d encourage you to keep an open mind.

My own views on this have evolved quite a bit and very rapidly. My very first reaction to hearing about a novel virus effecting an area of China was one of skepticism. The data I saw suggested that it wasn’t particularly dangerous for most people and it was pretty far away so it didn’t feel like something that was emergent. Even as it started to spread in Asia and Europe, I dismissed some of what I was seeing. As it got to the US I spent a lot of time talking about the “denominator problem” and just how little we really knew about how dangerous the virus really was because we didn’t really know how many people actually had it. Last Monday (that’s not even a week ago, for those of you playing at home), when we were trying to decide if we should go ahead and host our annual CEO Summit that was due to take place Wed evening through Friday of last week, I argued with my partners that we should continue with the event (fortunately I lost that vote). By Thursday we decided to close our office and ask everyone to work from home. By Friday I had pulled all in person meetings off my calendar and cancelled all non-critical meetings generally to free up some time. Last night I joined a growing group of colleagues calling for essentially closing down all social gatherings (bars, restaurants, churches, etc.).

Once views get entrenched it’s hard to change them (we’re watching as an entire major new network deals with this – or really fails to deal with this – in real time; it’s agonizing). I’d encourage everyone to step back from whatever their initial impressions were of the now unfolding crisis and view it with a fresh lease.

Take Decisive Action to Stem Covid-19 NOW

It’s hard to keep track of all the data around the current status and potential spread of Covid-19. The data are overwhelming, there is a lot of disinformation spreading, and the data and advice from various public and private sources are changing almost hourly. It’s a scary time, and as I wrote on Friday, a time to make sure we’re staying connected, even if we’re physically distancing ourselves from each other.

But what is becoming more and more clear is that we need to be taking bolder and more decisive action to stem the spread of the virus. And we need to be doing that NOW.

Rachel Carlson, CEO of Guild Education and Ken Chenault, former CEO of AmEx and current Chairman of General Catalyst, are leading a large (and growing) group of company leaders in pushing for a more radical and decisive approach – one that involves voluntary, but significant changes in our individual behavior. You can see their full post here. Foundry has endorsed this initiative (and both Brad and I were early signers of the document). We’re encouraging out companies to do the same. If you’re so inclined you can sign the pledge to take these actions in your own business here.

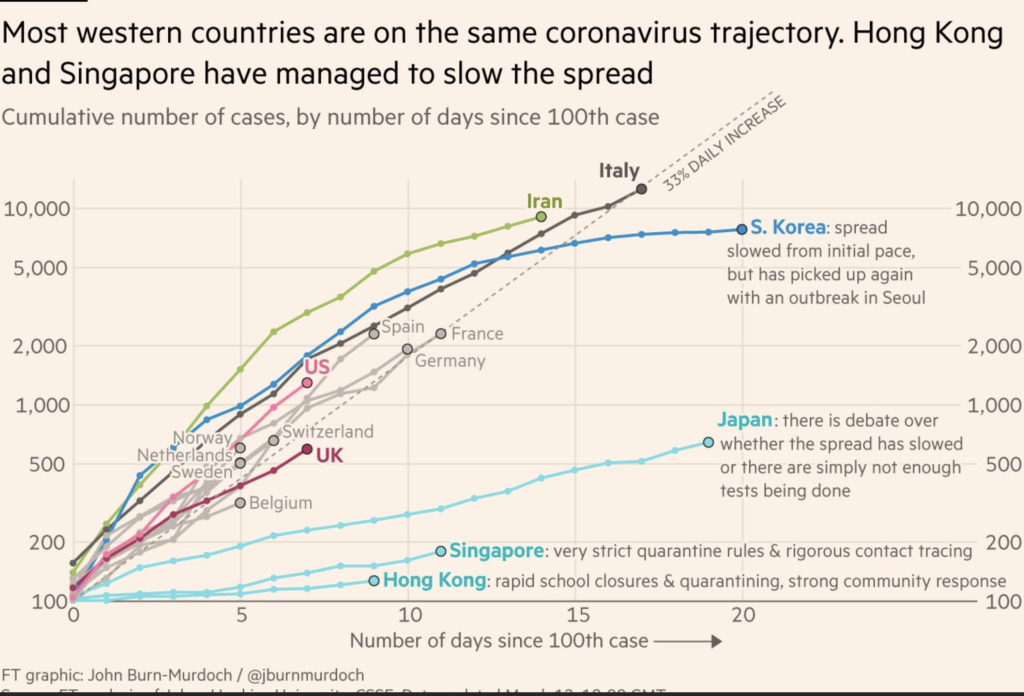

My wife pointed me to a great info-graphic that The Washington Post has put together that shows the effect of being more deliberate in the actions we’re taking to avoid community contact and therefore spread of the virus. We’ve all heard the term “flatten the curve” and The Post vividly shows how this works (in this exercise, everyone eventually gets sick but the effect of staying separated massively changes the infection curve). It’s exactly what we need to be doing to allow our first responders and medical system to stay on top of the crisis. It’s also the model that was followed in Hong Kong and Singapore. The graph below shows the effect that had on the spread of the virus there vs other countries. The difference is stark.

What actions should we be taking? Here’s what we’re outlining in the Carlson/Chenault-led initiative:

– Change our corporate policies to work-from-home

– Support our nations front line work-force (first responders, doctors, nurses, etc.)

– Ask our employees and friends to stop hosting or attending any voluntary social event of ANY size

– Encourage everyone to stop patronizing bars, restaurants, and gyms (we’re working on ideas to help support our local organizations, but we have to stop putting ourselves in places where we are in close contact with other people for the time being).

– Treat ourselves and each other kindly – we’re all under a lot of pressure and stress levels are high

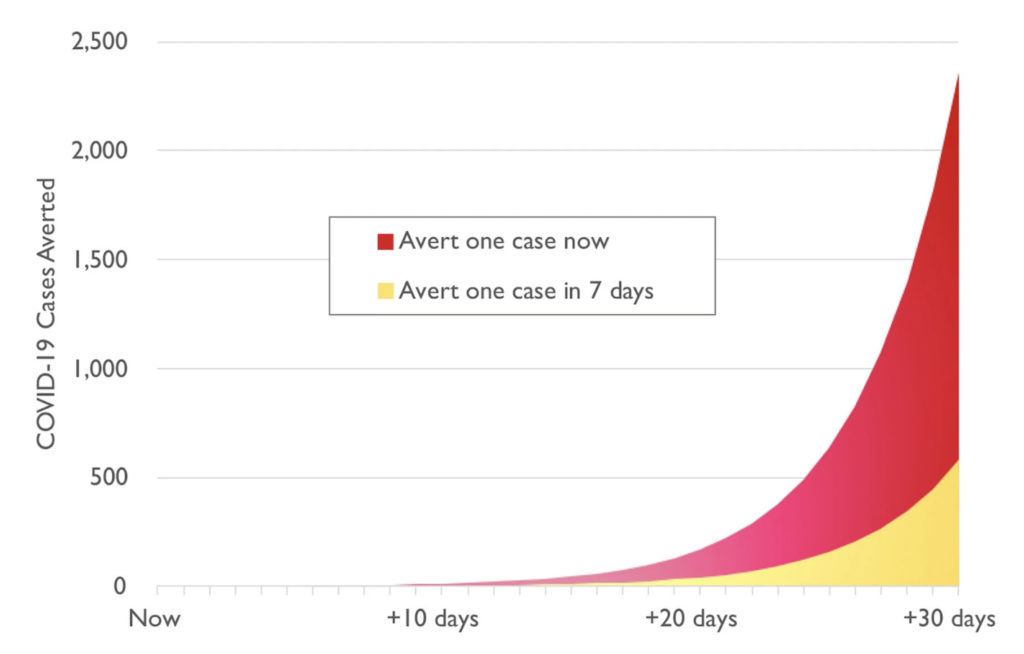

These actions are bolder than what our federal, state and, in most cases, local governments are requiring. But we believe government is not doing enough and that their lack of action is putting us on the steep curves of other countries who failed to implement a strong community response. We can and need to be bolder and take more decisive action. We don’t need to wait for government to require it – we can decide ourselves to do it. The graph below shows the effect of delaying to do so. Pandemics follow an exponential curve. The effect of averting a single case now vs averting one a week from now are dramatic.

We’re just beginning to grapple with the social, economic and emotional costs of what appears to be the most dangerous global pandemic we’ve seen in a century. We do know that we can take action now that will change the trajectory of the spread of the virus and significantly reduce the burden on our already strained medical system. Potentially millions of lives are at stake. This won’t be easy, but now is the time to take bold action.

#stopthespread

#leadboldly

Social distancing vs social isolation

I took a poll of the Foundry portfolio this morning to check in on the shift to Work From Home. As of today, about 1/3 of our portfolio companies have implemented a mandatory work from home policy. The vast majority of the rest are recommending people work from home but are not mandating it (meaning they’re not physically closing their offices). Only a couple are still operating with their offices fully operational.

We’re living in unprecedented times. Children are out of school. We’re shifting work patterns. Many of us have parents, partners or others that we’re close to who are immune-compromised or in some other class of person who is at higher risk for Covid-19. It’s a time of great emotional and physical uncertainty.

As we retreat into our homes and bunker down it’s important to consider the challenges many among us will face with that kind of forced isolation. There is a great deal of research on how we’ve slowly been creating a society that is less and less connected. The results are greater instances of depression, anxiety and other forms of illness. Humans are social animals. We need connection and our “tribe” in order to survive and thrive. Johann Hari did a wonderful job outlining the research behind this in his book, Lost Connections (there’s quite a bit of information on this on his LostConnections website as well).

I had this in mind as we were talking to everyone who works at Foundry yesterday, telling them that the office would be closed for the foreseeable future. I’ve been talking to many of the CEOs I work with about how to best support their employees through what can be an isolating and scary time. It’s critical in times of stress – and especially in times where we’re physically isolating ourselves – to foster a sense of community and belonging. We talked about this explicitly as a group in our discussion at Foundry and are taking extra steps to make sure we’re not just checking in with each other, but also that we’re creating a sense that we’re working together even though we’re working in separate places (this morning that resulted in a bunch of photos of our various dogs working with us; silly but it gave us the sense that we were all working together; we’ve also significantly stepped up our use of Slack and Voxer so we’re all in touch more than we were when we were physically next to each other in some cases). I think this is important for all of us to keep in mind. While its important to check in on how people are doing, creating a sense of normalcy to working apart; creating community and connectedness – at work, with our neighbors, with our children’s classmates and with our friends – is just as important as what we’re all doing to physically isolate ourselves to slow the spread of Covid-19.

Let’s make sure that we’re not confusing social distancing from social isolation.

Organizational Scaling

For the early part of your business you’re likely too busy to be spending a lot of time thinking about management structures, team optimization and how your business scales. You’re just getting shit done. And, even for experienced executives, making quite a few things up as you go along. The solution to many early scale challenges is to find something that works and then do more of it. That works great, right up to the point where it stops working completely. We’ve had a lot of companies go through scale challenges (I’d say typically around 100 people, but plenty of companies have muscled through that point and built 200 or even 300 person organizations without paying much attention to the scale structured needed to make that kind of organizational scale actually work. Here are a few things to think about/look out for based on our experience messing this up over and over again.

Don’t be the single point of failure. For good reason, CEOs often are the key decision maker early on in a business. You likely approve any major expenditure and certainly all new hires. As your business scales this doesn’t work. Maintaining control of expenditures in this way isn’t you being a thrifty CEO, it’s you creating a bottleneck for anything getting done and not empowering your team. Budgets and delegating and distributing authority (with clear limits and rules) is how this is better managed.

Matrix, don’t hub and spoke. While plenty of companies do some form of a management team/e-team meeting, many don’t in favor of 1:1 conversations with the CEO. This can sneak up on you as is often the product of an early team running around all over the place and often not in the same state or country, let alone the same room. So the CEO starts direct check-ins to make sure everyone is on the same page. Great. But that doesn’t scale and it doesn’t allow your scale VPs to work collaboratively on the business. An awesome off-site isn’t the remedy to this. Weekly meetings with everyone in the room – talking to each other, not just reporting back to you – is.

Your head of talent is a key manager and should report to the CEO. Gone are the days when HR reported to the CFO as a purely administrative function. Have a talent professional with a seat at the e-team table and have them report directly to you as CEO. That elevates the position properly in your organization, empowers them to be a driver in your business and will pay back dividends many times over in terms of reduced turn-over, greater transparency and alignment across the organization and fewer headaches for you as CEO.

Communicate. The larger you get the more more deliberate you should be about communicating across the organization. The company takes direction from you as CEO but it can’t read your mind. So communicate often and clearly with the entire team, not just your direct reports. One of my favorite examples of this is Scott Dorsey’s famous Friday Note. Scott led Exact Target from their founding to $2.5bn exit. Every Friday, no matter where he was in the world, he’d send a note to the company talking about what was going on with the business, what he was up to and sharing additional thoughts about the market or something interesting he was reading or thinking about. His employees loved it, it set the tone for the organization, and everyone know that they’d hear from the CEO directly every week. Not necessarily what you need to do, but find some way of communicating with everyone at the company on a regular basis.

Invest in systems. This one stands out – it can be hard to spend money internally when there’s so much [product/sales/marketing/etc] to do at your company. But growing past the startup stage can require an investment in some internal systems that help create alignment and facilitate the communication that I’m describing above. This comment goes beyond internal HR related systems and includes making sure that you’re not cheaping out on other systems that are critical to running your business (i.e., by limiting access to them to a small number of employees). Take a broad view of systems and make sure you’re not skimping out on the last 5% of cost that can drive outsized benefit.

Hopefully this has spurred some thinking about how to scale the management side of the business. I’d love to hear more ideas, so let me know what other things changed for you markedly when your company scaled past 100 or 150 people.

Polar Bears!

Kaktovik lies at the far northern edge of Alaska’s North Slope region, about 640 miles north of Anchorage (and almost 400 north of Fairbanks). Located on Barter Island and due to its location, is mostly cut off from the rest of the world. Everything – fuel, supplies, infrastructure, needs to be brought in either by plane (to a small, gravel, landing strip) or by barge – of which there are between 1 and 3 a season. It’s just about the farthest northern town in America (Utqiagvik, which used to be called Barrow, is slightly north of Kaktovik). During the winter, the sun doesn’t rise for 2 months. Despite this isolation – or perhaps because of it – Kaktovik is considered one of the best places in the world to see Polar Bears. Female bears with their cubs make Kaktovik their summer home (the ever receding polar ice is about 200 miles north) where they wait out the season in anticipation of the ice reforming starting in October so they can venture north to hunt seals. The town is populated primarily by Inupiat, who continue to practice some of their native traditions, including the hunting of whales (they’re allowed up to 3 a year under treaty with the US government). While they use the majority of the whale for food and other purposes, the remains are deposited in a “bone pile” that the bears feed upon. It’s also not uncommon to see a bear in the village itself.

Kaktovik lies at the far northern edge of Alaska’s North Slope region, about 640 miles north of Anchorage (and almost 400 north of Fairbanks). Located on Barter Island and due to its location, is mostly cut off from the rest of the world. Everything – fuel, supplies, infrastructure, needs to be brought in either by plane (to a small, gravel, landing strip) or by barge – of which there are between 1 and 3 a season. It’s just about the farthest northern town in America (Utqiagvik, which used to be called Barrow, is slightly north of Kaktovik). During the winter, the sun doesn’t rise for 2 months. Despite this isolation – or perhaps because of it – Kaktovik is considered one of the best places in the world to see Polar Bears. Female bears with their cubs make Kaktovik their summer home (the ever receding polar ice is about 200 miles north) where they wait out the season in anticipation of the ice reforming starting in October so they can venture north to hunt seals. The town is populated primarily by Inupiat, who continue to practice some of their native traditions, including the hunting of whales (they’re allowed up to 3 a year under treaty with the US government). While they use the majority of the whale for food and other purposes, the remains are deposited in a “bone pile” that the bears feed upon. It’s also not uncommon to see a bear in the village itself.

With Polar Bears in mind, Greeley and I ventured up to Kaktovik last week with Brad and Amy to see the bears and experience a few days far north (for all of us it was the farthest north we had ever been). Kaktovik is an interesting place – with a population primarily of Inupiat and at that only about 290 permanent population. But as one of two main gateways to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge it sees some tourist traffic during the summer months. Kaktovik is a desolate place, build on top of the alpine tundra and with little in the way of vegetation. There are two small motels, no restaurants (except for the facilities in the motels themselves) and only basic infrastructure. The people were very friendly but clearly hearty and self reliant. Most had long time family ties to the area. There is a small school there as well as a US Fish and Wildlife station. Industry is either government or related to tourism (not just polar bear watching but caribou hunting and fishing). From what I could gather the town in large part exists because of the stipends that Inupiat receive from the Alaska Native Corporation (royalties received from the US government; payback in the government’s mind for stealing their lands generations ago).

With Polar Bears in mind, Greeley and I ventured up to Kaktovik last week with Brad and Amy to see the bears and experience a few days far north (for all of us it was the farthest north we had ever been). Kaktovik is an interesting place – with a population primarily of Inupiat and at that only about 290 permanent population. But as one of two main gateways to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge it sees some tourist traffic during the summer months. Kaktovik is a desolate place, build on top of the alpine tundra and with little in the way of vegetation. There are two small motels, no restaurants (except for the facilities in the motels themselves) and only basic infrastructure. The people were very friendly but clearly hearty and self reliant. Most had long time family ties to the area. There is a small school there as well as a US Fish and Wildlife station. Industry is either government or related to tourism (not just polar bear watching but caribou hunting and fishing). From what I could gather the town in large part exists because of the stipends that Inupiat receive from the Alaska Native Corporation (royalties received from the US government; payback in the government’s mind for stealing their lands generations ago).

The experience for us was fantastic. We stayed at a place called the Marsh Creek Inn, which was very basic but comfortable, run by Tim and his family who couldn’t have been more welcoming. We ate all our meals at Marsh Creek and I was impressed by the fresh salads, bananas and strawberries (when Tim received the Strawberry shipment he came out to the dining room and announced “how about that – strawberries in Kaktovik!”; he later dipped them in chocolate and served them as dessert, which was pretty awesome). As we ate or wandered through town I kept marveling at how they manage to keep all of this supplied so remotely. That and what it must be like in the dead of winter.

The experience for us was fantastic. We stayed at a place called the Marsh Creek Inn, which was very basic but comfortable, run by Tim and his family who couldn’t have been more welcoming. We ate all our meals at Marsh Creek and I was impressed by the fresh salads, bananas and strawberries (when Tim received the Strawberry shipment he came out to the dining room and announced “how about that – strawberries in Kaktovik!”; he later dipped them in chocolate and served them as dessert, which was pretty awesome). As we ate or wandered through town I kept marveling at how they manage to keep all of this supplied so remotely. That and what it must be like in the dead of winter.

Each day we ventured out to watch the bears (returning for a few hours over lunch). And they did not disappoint. Seeing a polar bear in the wild is a remarkable experience and one I’ll never forget. They are massively powerful animals, but graceful and downright cute a times. At times they were active – play fighting with each other and roaming. At others we watched them just nap. It was incredible and I’m thankful for having had the experience. I don’t typically blog about vacations or trips that I take but I thought this one was worth sharing, along with some pictures of our time there.

The Markets Are Great . . . but Venture Outcomes Haven’t Changed Much

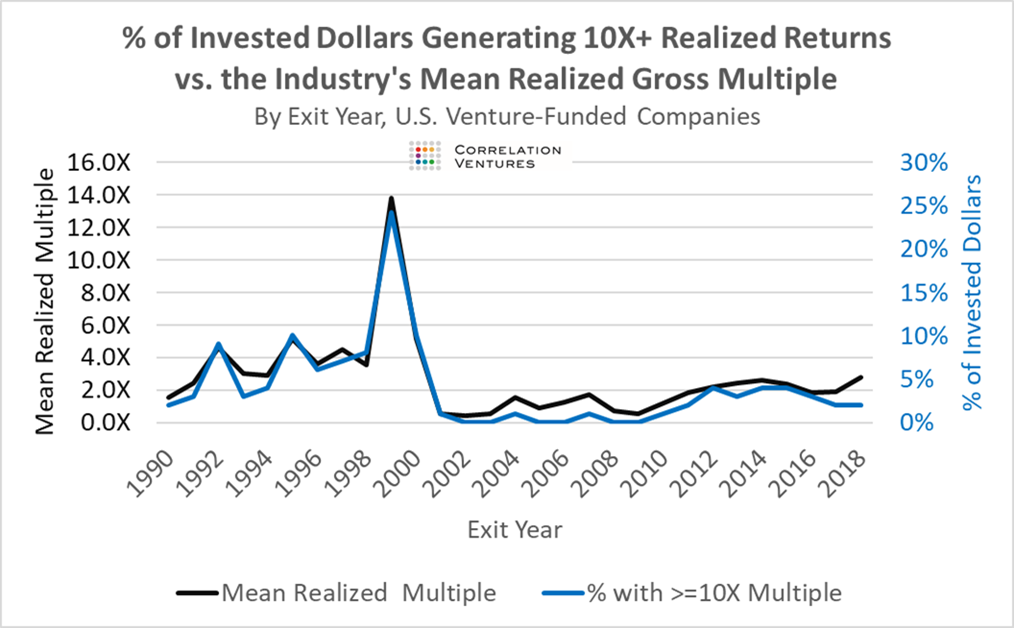

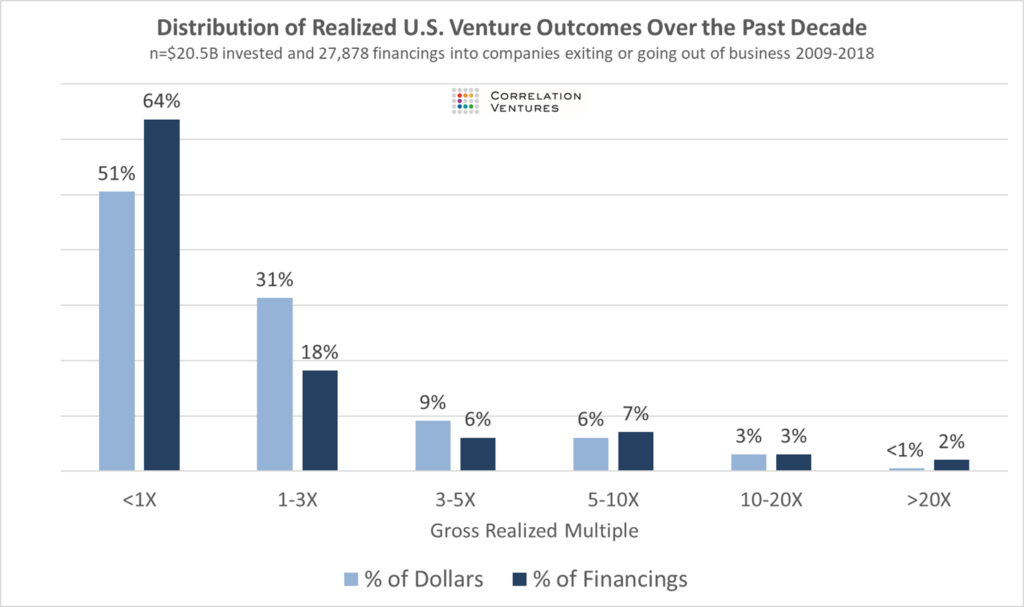

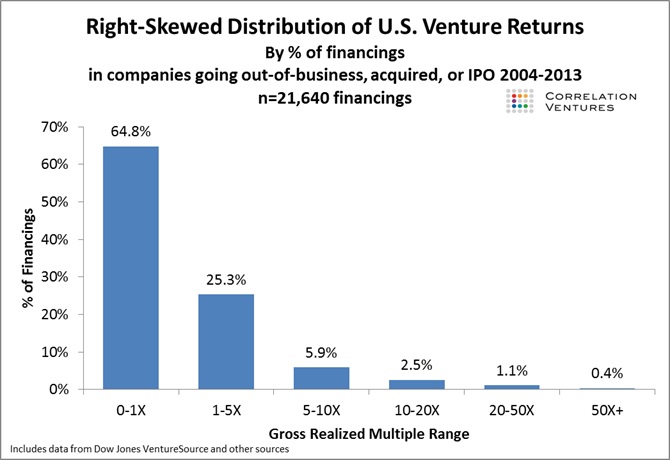

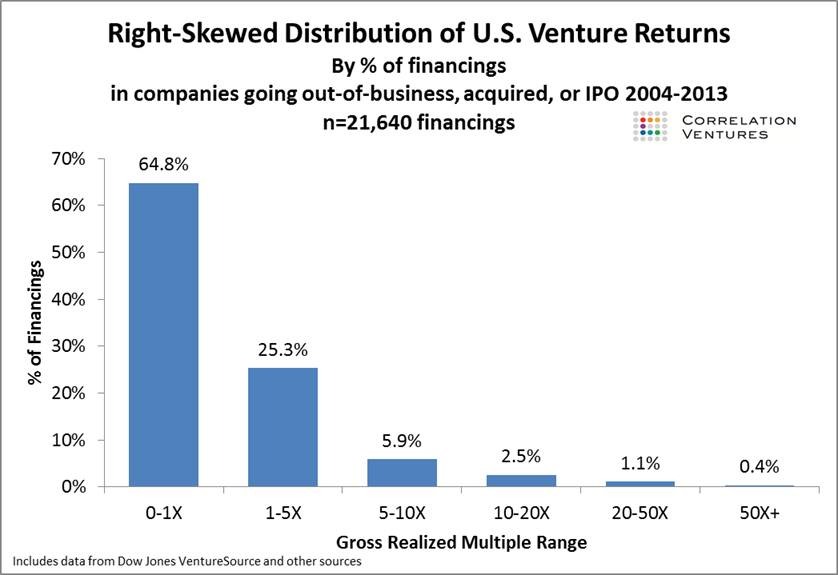

A few years back I blogged about the hard data behind venture outcomes and the challenge of creating a venture portfolio that produces strong returns. That blog post – which turned into one of my most read posts ever – grew out of a study done by Correlation Ventures showing the distribution of outcomes across over 21,000 financings during the years 2004-2013 as well as some of my own observations. The Correlation study produced a lot of interesting data and showed that the typical “1/3, 1/3, 1/3” model that many VCs talk about was significantly more optimistic than the reality of typical venture returns. The vast majority (almost 2/3rds) of venture financings fail to return capital. And only about 4% produce a return of greater than 10x. Pretty humbling. Here’s the graphic I used from that post:

These data are now getting old and VCs, LPs, and entrepreneurs have to ask if anything has changed – especially given the strong markets we’ve experienced over the past few years. Are ventures outcomes trending higher? Are they as skewed as they were during the ’04-’13 time period that the original study covered?

Correlation reran the data and produced some compelling data demonstrating that the market surges we’ve seen recently haven’t translated to meaningfully higher venture returns. Since 2001, financings that have produced a 10X+ returns have fluctuated some but remain modest.

Rather than breaking even, almost two thirds of financings lost money in the past decade and less than 4% produced 10X or greater returns. Despite the historic market we’ve had in the past ten years and the huge deals often highlighted in the press, venture capital returns haven’t shifted much.

Big hits remain a relative rarity and more than half of the capital invested into venture-backed companies loses money (interesting to see the data updated for dollars as well as deals – on a dollar weighted basis the numbers are more favorable at the low outcome end (below 3x) but at the high end of the outcome scale balance out). It’s as difficult today to find big winners as it was ten years ago and it remains just as important to find those deals if VC firms and their partners are to stay successful.

Note: Thank you to Correlation for allowing me to share these data as they were originally prepared as a private exercise for Correlation and their venture partners.

How Well Do Founders Do in Venture-Backed Exits?

A few years ago I wrote two posts – Venture Outcomes are Even More Skewed Than You Think, and Some More Data On Venture Outcomes – that challenged the mythology that only 1/3 of venture-backed deals failed and showed just how rare large (10x and greater) venture returns really are. I think the sharpness of the curve surprised a lot of people and contributed to a bunch of discussion at the time around just how rare “venture outcomes” really were. Not surprisingly, I was looking at the data through the lens of an investor and in so doing was only focused on how well investors fared in company exits (as a side note, I’m hoping to update these data now that a few more years of a bull market are behind us).

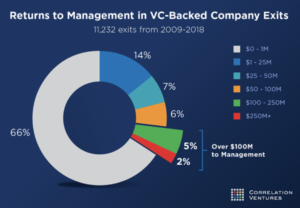

The data that underpinned the analysis was from Correlation Ventures, which is a fund that invests programmatically behind certain investment signals – thus the large database of transactions. A few months ago they put out another interesting piece of analysis that I thought was worth highlighting here (Trevor’s original post can be found here). In this latest post, they’re taking a look from the perspective of management teams – how much do they make when a company exits. In this case they defined “management team” as founders and C-level executives. And exit was a sale of the business, IPO or wind-down. The data set included over 11,000 events from the 10 year period between 2008 and 2018.

I thought the data were encouraging.

Not surprisingly, 66% of the time, management made very little (less than $1M) – I say not surprisingly because this generally maps to the venture side of the analysis, where roughly the same % of investments failed to return capital. In 20% of the outcomes, management teams made more than $25M. 7% of the time they made greater than $100M. The full details are below. I’ve also copied the graph from my original Venture Outcomes post so you don’t have to click through to see the equivalent data from the venture perspective.

Clearly, the risk of starting a business is high, but management success is generally aligned with investor success (although remember, taking venture isn’t for everyone). There are plenty of ways that management incentives are not aligned with investor incentive (the most often talked about and obvious one being that investors place many bets while management teams place a single bet in the company they’re working for; this has been somewhat mitigated by the shared equity pools and, more so, by the advent of funds that help employees exercise their options when they leave a business so they can keep much of their upside as they move from job to job).

But at a high level, when companies do well, management teams do well. Which is good to see some data on.

How much should you be paying your auditor?

With April 15th right behind us, I thought this would be as good a time as any to write about the fun topic of Audit and Tax Prep fees for companies. I know you’ve been waiting for this, so here it goes…

While audits can sometimes feel like overkill for startups (certainly early ones), they’re generally pretty good hygiene. As a practical matter, most lenders will require them, so if debt is a potential part of your cap structure you’ll eventually need one. And most major investors will also require annual audits (we sometimes waive this for seed stage companies, although even then it can make sense). And, of course, if your company is acquired you’ll typically need to provide audited financials to the acquiring company.

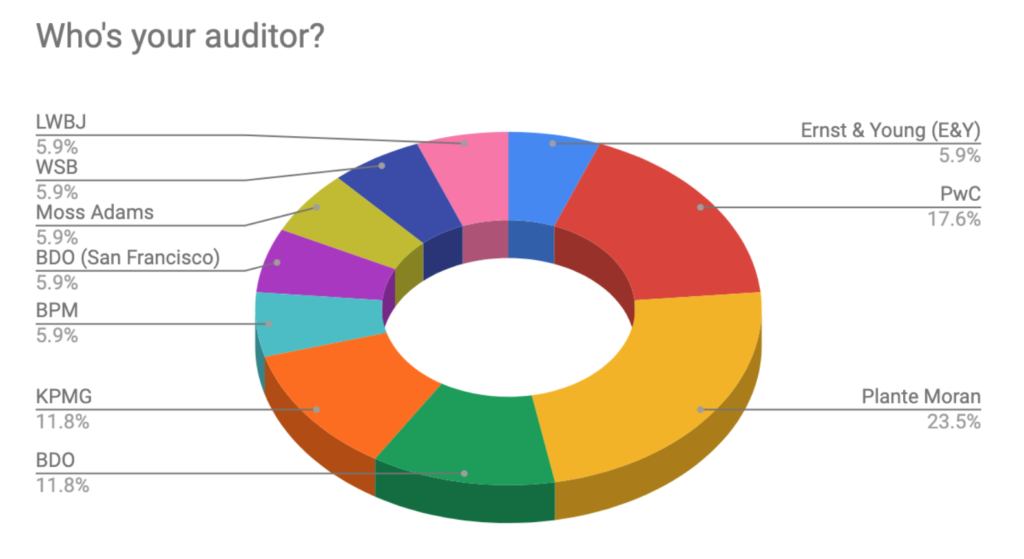

First, let’s talk about who is doing the auditing. There are plenty of solid providers out there, including your brothers’ friends’ wife (more on that later) for all sizes and types of companies. Most of our companies start with a firm outside of what’s commonly referred to as the “Big 4” (Deloitte, E&Y, PwC AND KPMG). Most typically companies use a firm from the tier just below that, although we do occasionally have firms use a regional auditor. There’s nothing wrong with that approach, but do keep in mind that as your company grows you may find yourself in the position of outgrowing your firm’s capabilities. In my almost 20 years in venture we’ve seen the big audit firms come in and out (and in again) of the venture stage company market. They’re not set up to compete well on price for smaller companies but when they’re “in” market they’ll discount for a year or two with the hopes that venture companies grow quickly to mid-stage companies and better fit their fee model. When that doesn’t happen there can be some conflicts as the larger audit firms try to push on pricing and/or use more junior staff to save margin. Selecting an audit firm is typically a multi-year commitment (and should be – bouncing around from firm to firm is time consuming, looks like you’re trying to hide something, and creates inconsistencies). In fact, we typically recommend that when you are bidding out audit that you get multi-year pricing to be sure expectations are aligned on both sides.

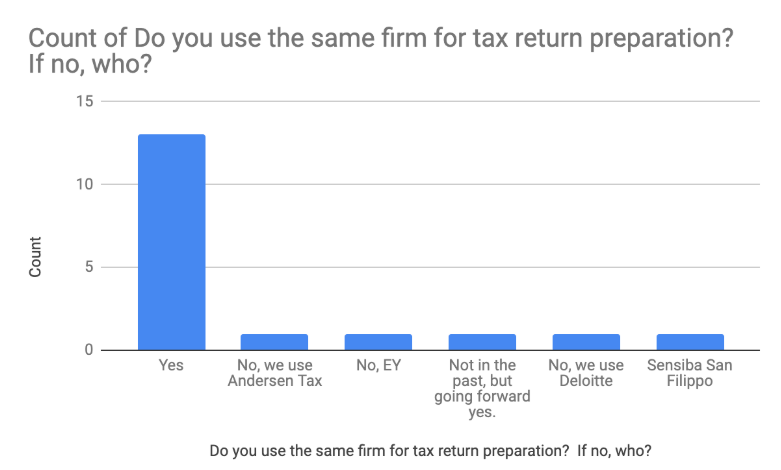

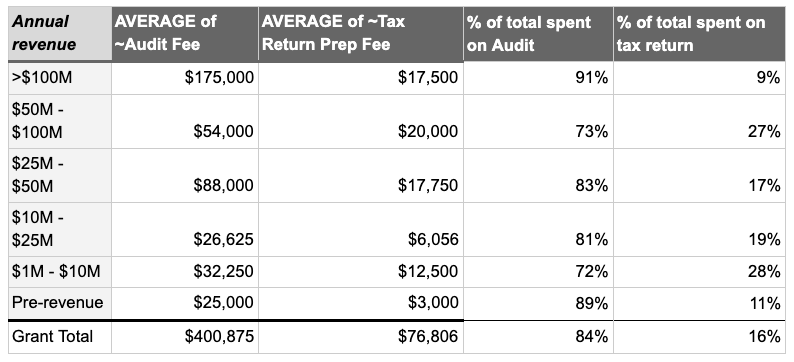

I was curious what fees we were seeing in the portfolio at Foundry so we sent a survey to some of our CFOs to get a sense for what firms they were using and what they were being charged. The charts below are based on those responses (18 in total, so just a sub-set of the portfolio).

You can see what I was describing above. Some of the companies in our survey do you Big 4 audit firms, but the majority use someone from the next tier down.

You can see what I was describing above. Some of the companies in our survey do you Big 4 audit firms, but the majority use someone from the next tier down.

I was a bit surprised by this next chart – the majority of our companies use the same firm for audit and tax prep. There’s convenience to this for startups – especially with limited finance staff – but as you grow it’s more typical to use a different firm for audit and tax.

Here’s the key slide and what led me to the survey in the first place; fees. This generally falls in line with what I expected – there’s an audit floor in the $25k range that’s hard to get much below, but it doesn’t really start scaling until you reach $10M or more in revenue. From there it does scale up, but is dependent on factors such as the complexity of your revenue recognition, the number of jurisdictions you operate in, etc.

With states now paying more attention to nexus and the sales tax landscape post Wayfair, many of our companies are paying more attention to the states in which they file (below we’re talking tax, but there’s also the related question of what states you need to register in; often they’re not the same as there are different thresholds for each). Obviously the graph below is just illustrative that companies are paying attention to this, as w/o knowing the specific businesses in question it’s not possible to say if these numbers are low or high relative to where they should be. But they’ll almost certainly be going up as companies pay more attention to this.

Hopefully these data are directionally interesting and helpful. We’ll plan to run this survey regularly and pull in some more data points.