Focusing on Actions, not Results

I just had a conversation with an entrepreneur I’ve worked with for decades that resulted in an insight that I thought was worth sharing more broadly. We were talking about managing teams and in this case the challenge of getting some of his exec team focused on broader goals and the end result we’re driving for in the upcoming year (a big growth year for this business). The solution we outlined was to focus on actions (concrete, clear, definable) vs. the more vague set of results that we had been trying to align everyone around. We’re still driving to the same outcomes but the leap was too large in a couple of cases for people to get their hands around. By focusing on actions we moved a strategic conversation to a tactical one that each exec could internalize and the end of year results became the outcome not the driver, as they ultimately should be. Every journey starts with a step…

BREAK THE INTERNET TO SAVE NET NEUTRALITY

We have just hours. The FCC is about to vote to end net neutrality—breaking the fundamental principle of the open Internet—and only an avalanche of calls to Congress can stop it. So we decided to help “Break the Internet” on our sites. You can also support on Twitter, Tumblr, Youtube or in whatever wild creative way you can to get your audience to contact Congress. That’s how we win. Are you in?

More info here.

How Startups Actually Grow

We’ve all seen the growth curve on the left – all successful startups strive for a version of one. But in reality, the notion of a smooth growth curve actually masks how most successful companies truly grow.

We’ve all seen the growth curve on the left – all successful startups strive for a version of one. But in reality, the notion of a smooth growth curve actually masks how most successful companies truly grow.

Our experience at Foundry suggests that if you blow up the growth curve you’ll find that companies grow linearly and that what creates the log curve is a series of small changes that either change the slope of the growth (it’s still linear, but now growing faster) or that “jump” the growth curve up (growing at the same rate but now from a high base). Examples of things that fit in the first category are changes in sales efficiency, successfully adding to the sales organization, establishing channel relationships that add predictable revenue, etc. Typically these are small and change the slope of growth only a bit at a time. But over time they add up. Examples in the 2nd category are generally either changes in product that increase pricing across the board or landing an outlier large customer. These tend to be bigger, more obvious, and less frequent.

Over the years we’ve found it helpful to think about growth in these categories – often asking out loud: “does this change the slope of our growth trajectory or jump the line?” so we’re on the same page about what the intended effect of an initiative is. It’s also helpful to step back from a several year growth plan to actually consider the levers that change the slope of the line. There’s no doubt that growing a startup is hard work. Sometimes it’s helpful to take a step back to really understand how small moves add up to the magic growth curve we’re all chasing.

Friday Fun #3

Vote FOR a renewable energy future by voting AGAINST the Boulder muni

I’m really frustrated with the way many from the the pro-muni block in Boulder have misappropriated the idea that being for municipalizing our local utility infrastructure (condemning the Xcel’s local grid and forming a city-owned and operated electric utility) is the only way to move Boulder towards the goal of 100% renewable energy. They’re trying to co-opt the idea that a vote against muni is a vote for fossil fuels and a vote for it is a vote for renewables. I couldn’t disagree with this line of thinking more. In fact I think the opposite is true – a vote to continue the Boulder muni effort is the wrong way to go about pursuing the goal of lessening our dependence on non-renewable energy sources.

I’m really frustrated with the way many from the the pro-muni block in Boulder have misappropriated the idea that being for municipalizing our local utility infrastructure (condemning the Xcel’s local grid and forming a city-owned and operated electric utility) is the only way to move Boulder towards the goal of 100% renewable energy. They’re trying to co-opt the idea that a vote against muni is a vote for fossil fuels and a vote for it is a vote for renewables. I couldn’t disagree with this line of thinking more. In fact I think the opposite is true – a vote to continue the Boulder muni effort is the wrong way to go about pursuing the goal of lessening our dependence on non-renewable energy sources.

This weekend I wrote a long note to a local friend who came out in support of municipalization. I thought it was worth sharing to a broader audience – especially the answer to his question of why so many from the Boulder tech and business community are against continuing the muni effort (see for example here and here).

Is your sales problem really a product problem?

Not suprisingly when companies are having issues in sales they look to their sales or and sales leadership for the source of the problem. In the cliche example (but one which happens all the time) sales will loop in marketing (“we’re not getting enough leads”, “the leads aren’t high quality enough”).

Not suprisingly when companies are having issues in sales they look to their sales or and sales leadership for the source of the problem. In the cliche example (but one which happens all the time) sales will loop in marketing (“we’re not getting enough leads”, “the leads aren’t high quality enough”).

But typically product is left out of this mix.

To be clear, there are plenty of sales related issues that are directly attributable to poor sales processes, bad training of sales resources, poor time management, etc. But often overlooked is the role product plays in sales challenges. I’m not writing this to offer a ready made excuse for sales teams that aren’t executing but as a reminder to executive teams that when you’re struggling to understand sales challenges be sure to look at closely at product. I’d suggest looking both at how existing customers are actually using your product (often not well understood by companies) and comparing that with both the type of customer you’re targeting (which may be very different than your current mix of customers) and what features they require. I can’t tell you the number of times we’ve looked more closely into this question and found that the problem we’re actually solving isn’t well mapped to a shifting target in sales. Or where there are specific product features that we’re lacking that are preventing product adoption but for whatever reason that feedback insn’t coming through as part of our sales process.

Seasoned execs know to beware of the “if we only had feature X we’d be selling more” feedback from sales and to dive more deeply into what the data are showing them about actual product usage. But more often than it’s given credit for product is key part of sales challenges.

For an older post I wrote on companies making the shift from early product to sales focus see here.

The Feature -> Product -> Company Continuum

I’ve been thinking about the continuum between a feature, product and company a lot recently. Specifically the challenge that companies have as they move across this continuum, how rare that last category really is, and the combination of product idea and market potential that is required for companies to actually make it to Company status.

I’ve been thinking about the continuum between a feature, product and company a lot recently. Specifically the challenge that companies have as they move across this continuum, how rare that last category really is, and the combination of product idea and market potential that is required for companies to actually make it to Company status.

Most companies begin life somewhere between a feature and a product. They’re started by an entrepreneur trying to solve some problem that s/he finds compelling and generally that problem is a feature of some larger set of problems. At this stage most entrepreneurs are given the advice to “focus”. It’s good advice (and advice I give all the time) but does sometimes perpetuate the feature-ness of the business – you spend your time and effort narrowly on a small number of related features and while you may have some inclination for how these stitch together into a larger idea it’s not fully thought through yet.

Often that’s basically where companies end – as a collection of features that if you squint hard enough feel like a product but often times are really somewhere in between.

One of the key – and often mis-understadood – challenges here is that the journey down the company path relies not just on the breath of the product that is being built but also on the overall size of the opportunity as well as how universal the solution you’ve built is to that market. The bigger the opportunity and the more ubiquitous the solution, the more focus can pay off. The smaller the opportunity or the more fragmented it is, the more focus just equates to building a feature not product or company. Take photography as an example. Instagram built a series of relatively simple (focus!) features – filters and frames – into a product. But the opportunity was so large they were able to turn that product into a company by stitching together its users into something larger than a collection of individuals using a bunch of features. Importantly here the features were ubiquitous across the user base – they solved a problem that many, many people had the need for (“how can I make my pictures look better?”) in a way that worked for everyone (“add a filter and put it into frame and my pictures look amazing!”). Contrast that to email management, which was a neat feature that never really graduated to a product. In that case the market was absolutely massive (everyone uses email and almost everyone complains about it) but the solution so fragmented (your version of solving your email problem is just too different to mine) that it never gained traction.

Features provide specific point value to users. Products stitch together related features into bundles that are essentially universal in their need across the problem set you are solving (put another way, if each of your users buys your “product” for a different reason you’ve probably just created a feature set, not a true product). Companies have product that is broad enough in its use and impact that a huge number of users gain value from it in a market that is both large and where the user need is similar enough to drive broad adoption of the same solution.

Friday Fun #2

Friday Fun – #1

The world needs more humor (or at least I do). I’ll be posting some here every Friday. Enjoy!

Today’s #FridayFun is one of my favorite all time SNL skits.

More Cowbell – Saturday Night Live! from Robert J. Lunte on Vimeo.

How to value your SaaS company

If you read my blog regularly you know I love (LOVE) metrics.

So no surprise that when River Cities Capital released an overview of SaaS operating and valuation benchmarks, I hung on every juicy detail. It’s chocked full of them – I’d highly recommend your reading the full report. But if you’re too busy for that, below are some of the key take-aways. I’ve added color commentary of my own that’s more relevant to earlier stage companies as well.

The methodology here was great. They took the 92 public SaaS companies and analyzed their key operating metrics. Beyond that, they actually went back in time and looked at the earlier stage periods for these companies so we can track how some of the world’s best SaaS companies performed at revenue levels more akin to a typical Series B business.

The “Rule of 40” is important. The rule of 40 is a benchmark that adds growth rate and EBIDA together. The idea is that if the addition of these two numbers is greater than 40% your business is on track. The valuation metrics show this clearly. Companies in the study that scored 40% of greater had TTM revenue multiples of 6.4x on average. Companies that scored between 20% and 40%, 5.3x, 0%-20% 3.8x and below 0% 1.9x. Healthy SaaS companies balance growth and profitability.

At IPO only 7 of 39 companies that have gone publics since 2013 had positive EBITDA. More on this below, but growth is more important than profitability, subject to the balance in the rule of 40 note above.

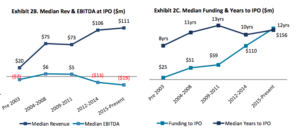

There are a ton of private SaaS financings. In 2016 there were over 2,000 financing rounds of private SaaS companies ($18.5Bn invested). Over 2,000 different firms participated in these rounds. This has contributed to companies raising more money than in the past before they go public (almost $100M on average for SaaS businesses that went public after 2011 vs. less than half that for those that went public before). It’s not clear from the study how much of this increase is going to shareholder liquidity, but clearly that’s driving some of this difference. Note in the graphic below the next point how this number has been increasing over time.

The average SaaS company is now 12 years old and has over $100M in revenue at the time of their IPO . See the graphs below.

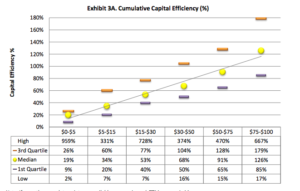

Capital efficiency was not as good as I was expecting. The River Cities study measured the ratio of revenue to money raised. Not surprisingly companies raised well above their revenue level in the earlier stages as they built product and sales and marketing. The curve goes up for sure, but was lower (i.e., had a lower slope) than I expected. But note the increasing divergence between higher performing companies (3rd quartile and better) vs average. The better companies more quickly become capital efficient (in the $30-$50M revenue range) vs. their average peers.

Interestingly growth and capital efficiency stats are down. Companies who went public after 2011 are less efficient with their capital and growing more slowly than their pre-2011 IPO peers. I imagine this is in part due to secondary liquidity (driving presumably by larger funds driving larger check sized into pre-IPO companies) – this counts as money invested in the capital efficiency score but in actuality doesn’t reflect money used to grow the business. This also may reflect the overall crowding of the marketplace and increased competition these businesses are facing.

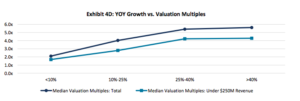

Growth still matters. I’ve written about the growth imperative before (and it’s counterpart the profit imperative). While not quite as crazy as it was in the fall of 205 when I wrote that first post, growth still matters. The chart below illustrates this. Interestingly at the time of IPO growth above 40% doesn’t move the needle (I’ve heard this from bankers as well before seeing these data). Top performing SaaS businesses grow quite quickly. The average public SaaS business took 6 years to go from $5M TTM revenue to over $100M (but worth noting that Concur, Ultimate Software and Vocus each took 11 years to do the same and ultimately became quite successful). Page 17 of the report digs into some additional data that felt too detailed for this summary but is worth looking at relative to the nuance of these growth rates from various revenue starting points.

Not surprisingly churn matters. Ultimately churn is a drag on growth and on sales efficiency. Good SaaS businesses retain > 85% of their customers and have close to 100% revenue renewal rates when including upsell. You’ve probably heard this from your investors before, but there’s a reason for that.

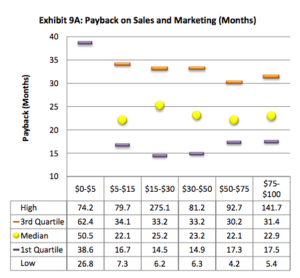

Sales efficiency was not as good as I expected it to be. I generally prefer CAC payback (vs LTV to CAC ratio) – especially for earlier stage businesses. And as a rule of thumb for businesses in our portfolio we target payback periods of 12 months or less. The study actually showed that these payback periods were longer than I would have expected with medians across company size closer to 24 months than to 12 (note in the graph below the meaning of quartile is flipped from the efficiency graph above). I have an upcoming post about this but a company’s ability to invest in longer payback periods relates closely to both the capital on its balance sheet and it’s access to additional capital.

Verticalization. There are some interesting notes in the report about greater efficiency for vertically focused SaaS businesses which I initially found counter intuitive and are worth considering in the context of your own SaaS business. Overall the SaaS market is becoming more vertically focused as, I think, a natural reaction to specialization in the industry (not to mention crowding in the marketplace as companies seek more specific niches for their products).

Hopefully the benchmarks I summarized here will be helpful to you as you think about your own business’ trajectory relative to your peers. Again, I’d urge you to read the full report as River Cities did a really nice job of analyzing a large data set and presenting the information in an easily digestible format.