Trump’s Legacy of Racism

As I listened to Kamala Harris and Joe Biden give their speeches from Wilmington on Saturday, I was struck by the contrast they offered to the rhetoric we’ve heard coming out of the White House for the past 4 years. Perhaps I had forgotten what ‘normal’ actually was. Both Biden and Harris spoke to the entirety of America – those that voted for them and those that didn’t. They spoke of character, honesty, science, and a belief that our strength comes from collective action, not from divisiveness. I woke up Sunday morning, as I imagine many of you did, with the feeling that a weight had been lifted from my shoulders. That, while America remains surprisingly divided, we’re back on the right track. I was struck by the outpouring of pure emotion we saw, not just from around America but from around the world. It will clearly take us years to heal from the divisiveness, hatred, and animosity that our soon-to-be former president stoked and thrived on. And without question, there are voices around the country who feel marginalized and that they have been left out. We need to acknowledge that and understand why 70 million people believed that the right conduit for their voice was a racist, bigoted, selfish, lying autocrat.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the legacy Trump leaves behind – especially his legacy of racism and hatred – and wanted to share a story to put some of that thinking into context.

Trump took bigotry and hatred, that had clearly been simmering just below the surface in this country for centuries, and brought to a boil. He made it acceptable and seemingly righteous to be racist, sexist, homophobic, and generally intolerant (if not malicious) towards anyone that is somehow “different.” And while I think it’s a mistake to paint all Trump voters with a broad brush, certainly a vote for Trump was at least a statement that these things weren’t a deal-breaker. It’s ok to vote for a racist, as long as you get X (whatever that thing is that you think is more important than character and integrity).

Last week, our family dealt with a situation that was a reminder just how harmful this embracing of racism and intolerance has been to our society.

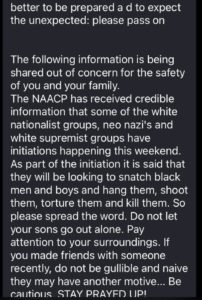

Late Thursday night, around 11 pm, we received a call from our daughter. She had been alerted by a well-intentioned friend that the NAACP was circulating a warning that white supremacist groups were plotting to kidnap black men and boys with the intent to torture and kill them. She was worried about her brother, who is black, as well as her friends at school who are black and brown. I can’t tell you how upsetting it is as a parent to know your child is up late at night worried about themselves and their family because they are targets simply because of the color of their skin.

Late Thursday night, around 11 pm, we received a call from our daughter. She had been alerted by a well-intentioned friend that the NAACP was circulating a warning that white supremacist groups were plotting to kidnap black men and boys with the intent to torture and kill them. She was worried about her brother, who is black, as well as her friends at school who are black and brown. I can’t tell you how upsetting it is as a parent to know your child is up late at night worried about themselves and their family because they are targets simply because of the color of their skin.

As parents of two black children, we’ve learned a lot about the state of race in our country in a way that our privileged, white upbringing (even in liberal households) didn’t allow us to understand. When a family of black children refers to “the talk,” they’re not talking about the birds and the bees. They mean the talk that black families have, to tell their children to watch out. To be careful about how they interact with people in authority. To explain to them that they will likely be targeted (pulled over by police, followed, etc) because of the color of their skin, but that they need to be careful in diffusing those situations, lest they be in harm’s way (like somehow this racism is their fault). We’ve already seen our kids be followed and targeted because of the color of their skin. In our family, we had “the talk” when our son was just 8 and our daughter was 11 (tbc, the talk is an ongoing conversation, not a one-time thing; over and over we’re forced to confront a racist society and racist acts and put them in context for our family).

And I can say unequivocally that overt racism has increased since Trump was elected. He didn’t invent racism, but he made it great again (to use his marketing term). We’ve experienced it as a family. Our kids have experienced it. So many others, too. I was recently talking to a black friend, a woman who has lived in Georgia all her life. She said the same thing. In 45 years she had never been called the n-word. The week after Trump was elected she was. And then repeatedly over the course of the last 4 years. Trump awakened something that was just under the surface of our society. And it’s not going to go away just because he is no longer president.

The supposed NAACP alert that our daughter sent to us turned out to be a hoax. It felt off when we saw it due to the language used, and when we looked online it turned out to be false. The idea that this warning was valid was completely plausible, given the social climate we’ve been living in and the hype we saw in the media over the past several weeks about potential election-related violence. And no doubt there were people out looking to do harm to those that they felt had caused their guy to lose the White House. While many people reading this are likely a few steps removed from the realities of what this really means to many people in our society, I wanted to share this story to provide a bit of direct and real world context. We were up that night thinking about whether our kids are safe, only because of the color of their skin, and sad and disheartened that they are afraid. Black parents (and other parents of black and brown children) around the country have to think about this all the time. That fact shouldn’t be news for anyone. Being white (and male), I can only scratch the surface of understanding what it really feels like to be a minority in the U.S.

Why a 47-Year Republican is Crossing Party Lines and Lessons in Life and Business from Her Daughter’s Painful Journey

The post below was written by a friend who wanted to share it but asked to stay anonymous (so as not to call her mom out). I think it’s really powerful, I hope do you as well. The strain this political season is putting on families is real. November 3rd will be here soon, for better or worse…

Why a 47-Year Republican is Crossing Party Lines and Lessons in Life and Business from Her Daughter’s Painful Journey

I’m very close to my mother and I have deep respect for her. However, there’s been a nagging distance between us since Donald Trump ran for president four years ago.

My mother has been a loyal Republican for 47 years. I’m an Independent. We often voted differently, but we could almost always find common ground because we share many of the same values, most of which she instilled in me.

She raised me to be an independent woman and to believe that I could do everything that my brother could do. She taught me to be compassionate, to respect all races and religions, and to always take the high road. Whenever I faced conflict and wanted to lash out, she told me to “kill them with kindness.”

When Donald Trump ran for president in 2016, I was sure she would cross party lines to stand for the values that she taught me to believe in. To my surprise, she did not.

Then, the infamous “Grab her by the” Access Hollywood tape surfaced. I was certain that this would change my mother’s mind. How could my mother, a woman who raised me to be a strong, independent woman, support a man who so viciously objectified women? Yet, she stood by him. She admitted that his behavior was disheartening, but excused it because he was a “man of a different generation.”

I mustered the courage to tell her how disappointing that was for me to hear. I revealed that when I was 16, I overheard my bosses engaging in similar behavior as we saw from Trump in that video. As a result, it took me ten years to overcome my fear of being alone in a room with any of my male colleagues or superiors. It wasn’t until I heard that tape that I felt that same feeling of fear and sadness that had taken me ten years to overcome. To hear this from the man who may be the next president of the United States and to know that my own mother was supporting him was hard to swallow.

She cried and said that she was so sorry that I had that experience. She then shared a story about how her father’s friend brutally sexually harassed her in front of my grandfather and my father shortly after they were first married. Neither my father nor my grandfather stood up for her. That, as you might imagine, was deeply hurtful to her, but she said that she was able to forgive them because they, like Trump, were good men who simply came of age in a different era.

Shortly before the election, she called to let me know that she had made her final decision to vote for Trump and that, while she was ashamed to admit it, she realized that she “was not ready for a female president.” In that moment, I realized that the woman who had raised me to believe that I could do anything my brother could do did not actually believe that to be true. While my instinct was to lash out, I swallowed my tears and thanked her for the tremendous amount of courage it must have taken for her to make that call.

In the four years since then, I had many more urges to lash out. I always stopped myself because my relationship with my mother is more important to me than winning a political argument. I even started to appreciate the opportunity to be so close to someone with political views so different than my own, and to admire her ability to stand by her convictions. There was this one moment when we were sitting with eight other people who just assumed that she had voted for Hillary Clinton. This woman started going on and on about how she just couldn’t understand how people could be so ignorant and selfish to even consider casting a vote for Trump. I watched my mother squirm in her seat for a few minutes until, finally, she took a deep breath and said, “I just want you to know that I voted for Trump and I don’t believe I did so for ignorant or selfish reasons.” The woman apologized, and my mother proceeded to calmly and respectfully explain why she had voted for Trump. We all emerged from that conversation with greater compassion and understanding for both sides of the aisle, and I was deeply proud of my mother. I watched her interact with people with opposing political views on many occasions without ever muttering a hateful word. I’m proud to say that we never shared a hateful word about each other, until the first presidential debate of 2020.

As I watched the debate, I thought about how horrified my mother would be if her four-year-old grandson emulated the behavior of our president. I composed an angry email to ask her how she could possibly be so stubborn and stupid, and to tell her that I would never forgive her if she voted for him. Because I’ve learned to never send an email when I am below the line, I decided against sending it.

The next morning, she called me to ask for my advice. She had spent her morning working out with her 75-year-old trainer, who is recovering from cancer, at a gym where masks are required by state mandate. She asked a woman who was not wearing a mask if she would consider complying with the law, and the woman aggressively lashed out at my mother, stating that it was her gym, too, and that my mother had no right to police her. It spiraled into a dramatic 45-minute argument that involved the manager and several gym patrons. She called me to run through all of the facts and content of the argument, and I told her that none of that mattered because the woman was reacting emotionally rather than rationally. I gave her some tips on how to relate emotionally without evoking defensive behavior and then I said,

“Mom, I am afraid we will all continue to experience more incidents like this if we elect a president who promotes bullying and aggression.”

The next morning, I woke to a Facebook notification with this post from my mom:

“My daughter said something to me yesterday. A vote for Donald Trump is promoting the example that a person who behaves and conducts themselves as he does can rise to be the most powerful leader in the world. I have been a Republican for 47 years, but I will be casting my vote for a kinder, gentler candidate.”

As I reflect on this five-year journey, I am struck by how much I have learned and how applicable these lessons are to all aspects of my life. Because, as entrepreneurs and VCs, we are in the business of changing behavior and disrupting the status quo, I thought it might be helpful to share some of the tips I learned along the way.

People respond poorly to shame. The more self-righteous I became, the more she retreated.

Understand your own patterns and the patterns of those around you. I’ve been on a parallel path to become more self-aware to deepen my knowledge of Conscious Leadership. This paid dividends to my business and to my conversations with my mother. The Enneagram and the Four Tendencies have also been particularly helpful.

Build close relationships with people with opposing viewpoints. This journey with my mother has helped me approach all sorts of opposing viewpoints with more compassion and empathy, and it has led to much more productive conversations.

The reason people give is rarely the real reason for their decision. Over the past five years, it became increasingly obvious that my mother’s behavior was driven by conscious and unconscious gender bias, and 65 years of programming herself to believe that the path to a virtuous life was to be a good Republican.

Uncovering the most important behavior driver is the key to driving change. At the end of the day, I believe my mother made this decision for me. Above all else, she is a mother who would do anything for her children. I think our journey would have been much shorter if I would have recognized and tapped into that from the beginning.

Never send an email in a state of anger. I am not sure why the mask incident was the straw that broke the camel’s back, but I am certain that had I sent that below-the-line email to ask her how she could be so stupid and stubborn to support Donald Trump, she would have cast her vote for Donald Trump.

During COVID, I’ve been asking myself what I want to be able to say about how I spent my time during this pandemic. I think I finally have an answer. I want to learn how to better resolve conflicts and drive change without evoking hatred and defensive behavior from the other side. I learned a lot from this five-year journey. I want to take what I’ve learned to drive far more change in far less time. I hope this story will help you do the same.

Come Join Us at Foundry: Hiring a Head of Network

Community is one of the driving forces at Foundry Group. We’ve kept ourselves intentionally small as a firm so we can keep our close connection with our portfolio founders from due diligence, to investment, and throughout the lifecycle of our investments. We strongly believe that fostering a mesh network model, which allows our network members to interact directly with one another, is the best way for all of us to learn, develop, and thrive together (vs the more traditional hub and spoke model that most firms end up falling into with partners as gatekeepers). Keeping this model improving and evolving is so important to us, especially in the current climate of social and economic change. We want our programming to be impactful, relevant, and able to serve our community in a way that promotes growth, development, collaboration, and ultimately successful company and fund outcomes. In light of this, we’re excited to announce that we’re hiring a Head of Network to expand and develop Foundry’s network programs. The full job description is below. If you or anyone you know fits the bill, please reach out to us at apply@foundrygroup.com. And please help us get the word out!

We’re looking for a leader to create a more robust, dynamic, and connected network program at Foundry Group. The Foundry Network, as we’ve been calling it, encompasses founders, CEOs, executives, general partners of our underlying venture capital fund investments, limited partners (our investors as well as other investors in the funds we have investments in), and other members of our ecosystem. We regularly bring together members of this community to connect, share, and learn from each other.

We know we’re just scratching the surface for how powerful this network can be. We’re looking for someone with the vision, background, experience, and skills to help us form the next chapter for The Foundry Network and to continue to grow and adapt how we work with our ecosystem in ways that support and empower our portfolio of companies and VC funds.

ABOUT US

Foundry Group is a venture capital firm that invests in early-stage technology companies and venture fund managers. Our passion is working alongside entrepreneurs to give birth to new technologies and to build those technologies into industry-leading companies. We also seek to leverage our experience and relationships as fund managers to help the next generation of venture firms create industry-leading investment businesses. We invest in companies and funds across North America.

SOME INITIAL THOUGHTS ON THE DETAILS OF THE POSITION

We’ve put a lot of thought into the development of our network and need help taking it into the future. Below are a few ideas we have about this position and the future of The Foundry Network. We’re looking for someone who can help us craft the vision, not just execute on ours. So take this as a rough draft.

As Head of Network you will participate in our weekly partner meetings and be a member of the senior team, which includes our CFO and General Counsel as well as all of the Foundry Group partners. You’ll have access to and know pretty much everything that’s taking place across The Network and our portfolio. At its core, this role will help strengthen connections between the people with whom we work- we believe strongly in mesh networks, not hub and spoke models. We are also excited to continue to expand The Network and the work we do in this area, such as in talent sourcing, data sharing, and community support.

We’ve historically engaged our network through active digital communication channels, in-person events, virtual events, webinars, and small group meet-ups. Many of these we’ll likely want to continue. Some we may together decide don’t further our key goals any more and will stop doing. And, most importantly, there are opportunities to expand beyond the base that we’ve created to support our portfolio in new and creative ways.

A LITTLE ABOUT YOU

It’s hard to put into words exactly what we’re looking for because the right person for this role could come from a number of different professional backgrounds. But there are a few things that we know will be important to success in this role and our firm culture.

This is a relationship-centric role and we are looking for someone who has a demonstrated aptitude for building and maintaining professional relationships. You have built your own network and are driven by helping others succeed and connecting the dots between people and companies. You have connections in and around the tech industry and have interacted with executives at a senior level in prior jobs and experiences.

At Foundry, we are not top-down managers. Our Head of Network will need to be comfortable working independently and own this core functionality of our business You will be included in and supported by the core team, but the role is primarily self-directed. While we will provide input and help you understand our goals for The Network, there is a lot of room for creativity and expansion.

In addition to creativity and vision, the ability to execute and achieve high-quality outputs are imperative for success in this role. Every senior role at Foundry – including our partners – is an individual contributor. We work collaboratively and in close coordination with one-another, but we do our own work and, while we have people on board to help with implementing events, much of the work of the Head of Network will be not just coming up with ideas, but seeing them through personally.

We live by a #givefirst mentality at Foundry, and we hope you can show us how you’ve done the same.

Finally, we want to be clear that this role isn’t a pathway to an investment role at Foundry. We want you to be excited about this role and this position. We think it’s a great opportunity to work alongside us as we continue to build out the Foundry Network.

EXPERIENCE

There is not one particular background that fits this role and we are open to candidates across the board. Given the autonomy of the role, we believe an individual with at least 7 years of professional work experience and who has previously held a senior level role will thrive. We’re focused on how your experiences drive your interest in this position and how they will contribute to your success in this role and at Foundry.

SOME DETAILS

Our firm is based in Boulder, but we’re open to you living anywhere, so long as (once travel resumes) you’re able to be here from time to time (most of our in person events are in Boulder, for example). This is a senior position and will be compensated as such. Additionally, we offer a generous benefits package (fully paid health insurance, along with a number of other benefits).

Foundry Group is an equal opportunity employer. We strongly encourage and seek applications from candidates of all backgrounds and identities, across race, color, ethnicity, national origin or ancestry, citizenship, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, veteran status, martial status, pregnancy or parental status, or disability. We are committed to creating a supportive and inclusive workplace.

NEXT STEPS

If you’ve read this post and think, “this is me!”, we’d love to hear from you. Please feel free to be creative and choose a medium that allows you to express yourself and give us a sense for whether you are a fit for this role. To apply, please contact us at apply@foundrygroup.com. We’d love to hear from you by the end the day on Friday, November 6, 2020 if you’d like to be considered.

VC Fund Returns Are More Skewed Than You Think

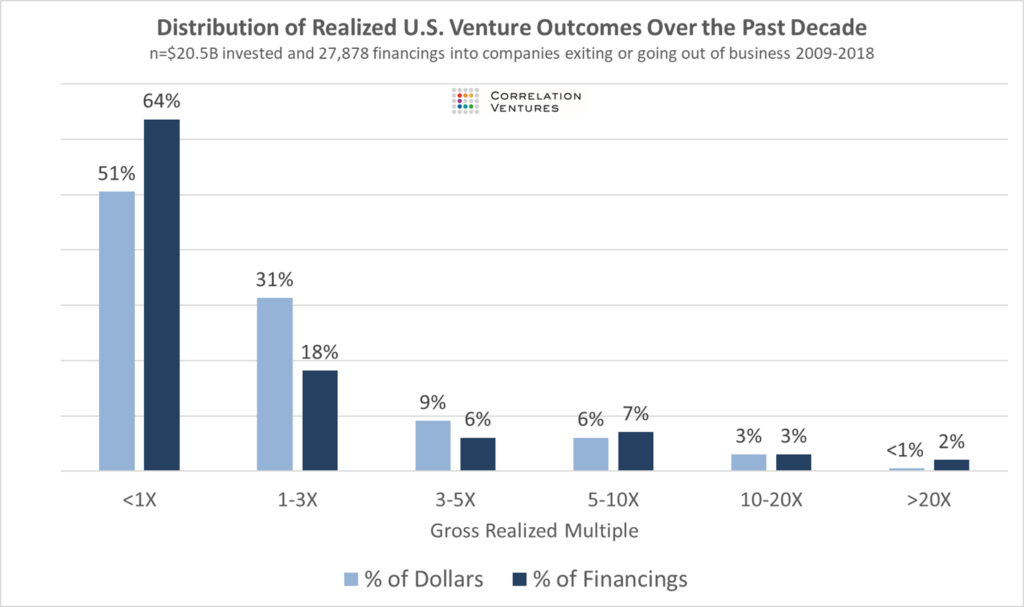

Some of the most popular posts I’ve written over the past couple of years were the two that focused on just how rare outsized returns for an individual deal are in venture capital. You can see the original posts here and here. In those posts I was analyzing data from Correlation Ventures that showed just how skewed venture returns are, specifically that 65% of investment rounds fail to return 1x capital and only 4% return greater than 10x capital.

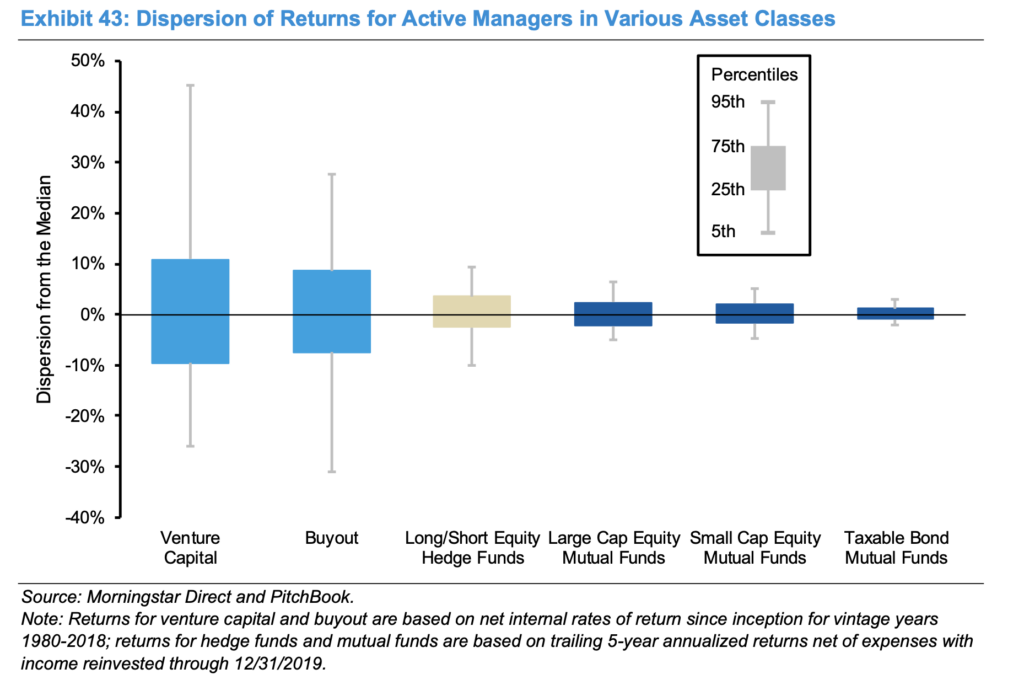

Ian Hathaway, who recently co-authored the second edition of Startup Communities with my partner, Brad, sent me the chart below which highlights how that translates to returns in venture capital as an asset class. I’ve seen versions of this chart before and while it’s not surprising it is always jarring to see it laid out like this. Specifically, the difference between the best performing and average performing firms are incredibly wide. Venture is a hits business and if you think about a typical venture fund of almost any size having somewhere between 25 – 40 investments, the chances of any one of those investments being a true outlier and returning a multiple of the fund are quite small. In order to have a successful fund, it’s almost a requirement that you have an outlier return for at least one of your investments (see below the chart for the math).

Some quick math highlights why this is the case. For example, assume a $100M fund with 30 investments. That’s a little over $3M per investment, and while there is some dispersion from the average across companies in a fund, it’s not a bad way to model it. But from the outcomes chart above (the first one) we know that on average only 1 (actually just fewer than 1) company in that group of 30 will return between 10x and 20x. And less than 1 will return 20x or greater (I’m using the company averages, the dollar averages are on a per round basis, which would make these numbers even worse). A 20x returner for a fund that on average invests $3-$3.5M in a company doesn’t return that fund. Taking the most aggressive end of these numbers would still only have this one company returning 70% of the fund’s capital. If you were going to have several of these, of course, that would work out for your fund. IRR will depend on the timing of cash flows but as a quick rule of thumb, venture funds look to return at least 3 times the invested capital – after fees, so more like 3.5x on a gross basis. That’s pretty hard to do without a true outlier return (50x+) and/or consistency of 10x+ returns that is simply hard to generate. And here’s where the dispersion comes in. The best funds do have multiple companies that return in that range. Or higher. But that means the median fund doesn’t have any. And that is why the average venture fund isn’t actually a particularly good investment and also why so many venture funds fail to return capital.

I thought about this a couple of years ago when I wrote about the optimal venture fund strategy and my conclusion was that venture firms should place more bets and have more exposure across a larger set of businesses. Obviously, those inside the industry argue that managers who are good at picking businesses would do better to own more of fewer businesses if they can show that they have the aptitude to invest in those that become true outliers. But given how rare they are, I wonder if that is arguably the optimal strategy. As David Cohen replied once years ago when I asked him what the key to being a successful venture capitalist was: “Luck”.

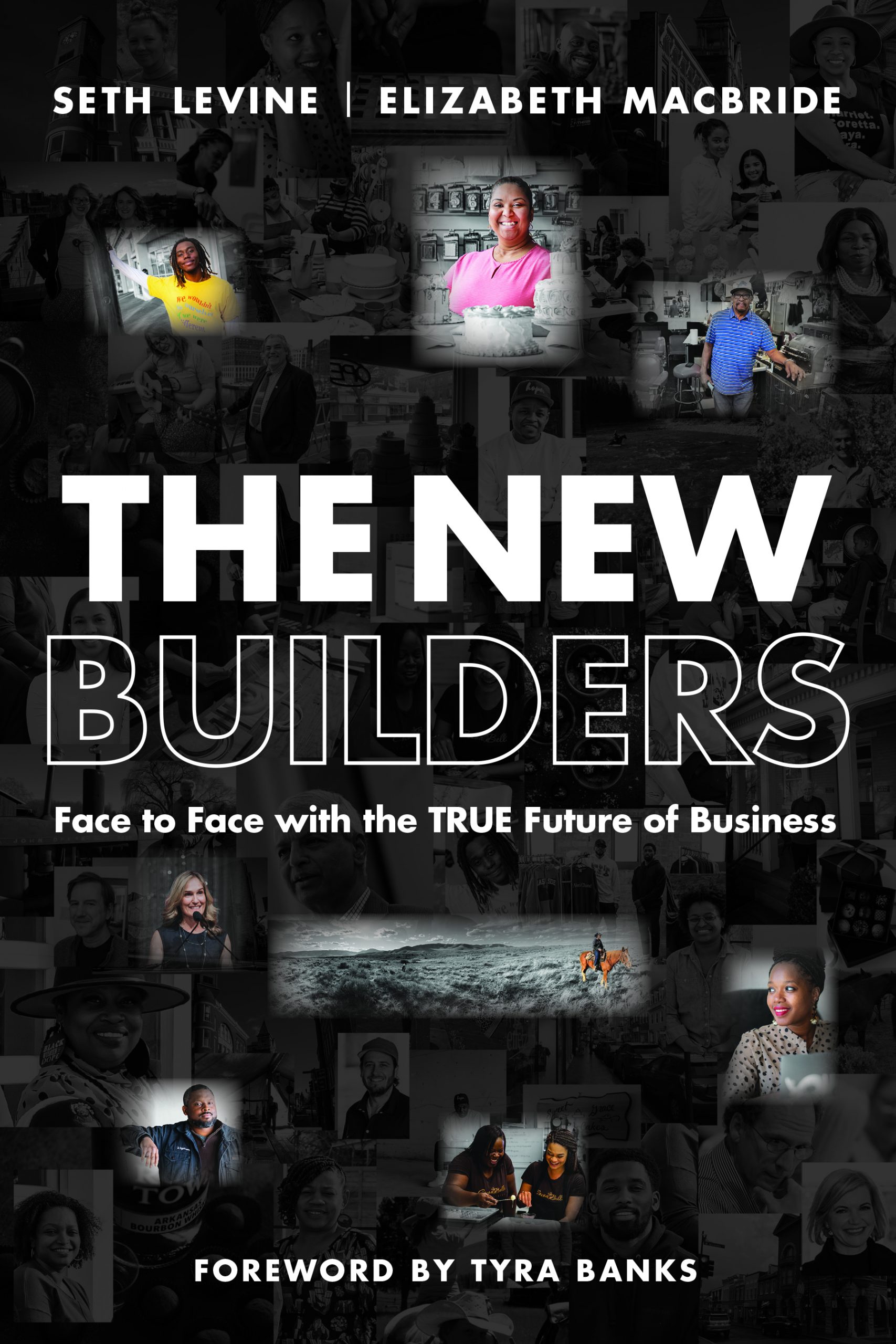

The Real Story Of America Is About Small

Below is an article I co-authored with Elizabeth MacBride of Times of Entrepreneurship (it was cross posted there on the ToE site yesterday). It’s a good companion piece to the OpEd we wrote for CNBC earlier this week. As many readers know, I’ve been working on a project highlighting entrepreneurs around the county. It’s been amazing to meet so many interesting grassroots entrepreneurs and hear so many compelling stories. I’m happy to be able to start sharing some of those. More details (and on our upcoming book on that subject) soon.

Why is America so divided? The loss of small businesses may be one answer. In research for our upcoming book, we found that small business owners often inhabit the shrinking middle ground of politics in their communities.

Out in the corral, Mark Cheff rubs some salve on Chinook’s leg above her hoof. Yesterday, two of the mare’s children were standing on either side of her, licking a deep wound caused by a sharp branch sticking out across the trail at just the wrong angle. Cheff thinks she’ll be OK by the end of the tourist season, this fall.

Out in the corral, Mark Cheff rubs some salve on Chinook’s leg above her hoof. Yesterday, two of the mare’s children were standing on either side of her, licking a deep wound caused by a sharp branch sticking out across the trail at just the wrong angle. Cheff thinks she’ll be OK by the end of the tourist season, this fall.

What the future looks like for his small business and the other 25 million — or maybe 22 million, now as the number of small businesses is shrinking rapidly — is less clear. Cheff has been a smokejumper, and owned a construction company. Now, with his wife, Claire, he owns a guide company in the Bob Marshall Wilderness of Montana. Like many of those businesses, the Cheffs, through 406 Wilderness Outfitters, contribute to their community as a source of economic activity, innovation and jobs — and in other surprising ways, as well.

Perhaps we’ll sound hopelessly old-fashioned as we say this. But as we have interviewed dozens of small business owners across the country for our upcoming book, we’ve found people of principal who value hard work; people who are passing along these values to the next generation of young people; people who are safeguarding the futures of their communities.

$5.9 Trillion Of GDP

As a country it seems we may have forgotten the value of these small businesses. America is home to a lot of big companies that dominate the headlines, mindshare and financial markets of our country. But the real story of American business has always been about small. Small businesses are “the lifeblood of the U.S. economy: They create two-thirds of net new jobs and are the driving force behind U.S. innovation and competitiveness,” says the SBA, which tracks business trends for the U.S. government. Small businesses accounted for 44% of all economic activity in the United States and were responsible for $5.9 Trillion in GDP in 2014, the last year for which data are available.

Even before the pandemic, we let our fascination with larger businesses – and the cheaper prices and greater convenience they provide to us – crowd out the evidence of what’s going at the startup and small end of the economy. The trend is that America’s small businesses have been in trouble for a while. Since the end of WWII, the US economy consistently produced net new businesses – more businesses started than closed down. This remained true through any number of recessions. However, this resilience ended with the Great Recession of 2008. The net number of new firms created in the United States was negative – more companies closed than were being started. The result was 117,000 fewer companies in 2014 than there were in 2007. Some 3.4 million jobs don’t exist today because of the decline in entrepreneurship during the Great Recession.

COVID-19 is extending the damage to small businesses much deeper than most people have realized. Even businesses that, by their nature, operate outdoors and with social distancing, such as wilderness companies, have not been immune to the economic effect of COVID-19. A number of the Cheffs’ week long, pre-booked trips have been canceled – devastating blows to a small family business that only runs about a dozen trips a season while “The Bob”, as the Bob Marshall is known to locals, is accessible (for much of the year, the trails are blocked by snow).

The Cheffs intend to make it. But many businesses will not. One recently released working paper by economist Robert Fairlie suggested that the number of businesses in the United States fell by 22% – 3.3 million businesses – between just February 2002 and April 2020. Not surprisingly, this was the largest drop ever recorded. And that was just in the initial months of the pandemic. We’re bracing for a fall surge that could devastate larger swaths of the American small business economy.

Only 20% Of Metro Areas Show Growth

When we lose small businesses, our divisions deepen. In the 30 years leading up to the Great Recession, fully 80% of metro areas experienced an increase in the number of firms annually. This trend was completely reversed by the Great Recession, after which only 20% of metro areas have seen an increasing number of companies created. New business formation has been depressed in most of the country.

Economists have been puzzling about the reasons for the decline in entrepreneurship. The answer is pretty simple. It’s always been hard to be a small business owner and lately it’s become even harder. Here’s one tiny example: health insurance. It’s unlikely the Cheffs would be in business without the help of the health insurance provided by Claire’s second job – she works as a teacher in the nearby Ronan public schools, a job that maps up well to her “off-season” of guiding. Good insurance is critical, because Mark Cheff has rheumatoid arthritis. In his smoke jumping career, he carried 120-pound packs for as much as 25 miles to fight the increasing number and severity of fires that occur in our nation’s wilderness. A hospital stay this winter didn’t keep him from playing a practical joke on the people who came to see him: Pretending to be brain damaged for the first few minutes of the visit.

What motivates a small business owner to keep going, working another job, or dealing with physical hardship, or the stress of making a payroll — during a pandemic? It’s true that many small business owners want to build wealth. A number succeed, which is good for the economy. But many more start businesses because of a sense of purpose or calling, because they want to pursue a passion or to create freedom and flexibility for themselves and their families. People faced with hostile work environments, especially women business owners and people of color, and older people, start companies to create their own opportunities where they can dictate their own work.

Overwhelmingly, as we interview small business owners across the country, we find they have stuck with it against the tough backdrop of the last few decades because they love what they do. COVID-19 may be the final blow for many more of them.

When we lose a small business, we lose that passion in action, which transmits values. It’s no accident that the Forest Rangers figuring out how to lobby for the trail budget they need to keep the Bob Marshall safe look to small guide companies for help. Or that the Blackfeet Tribe, as it fought a decades-long battle to void a mineral rights contract on its land, built a coalition of local small businesses to help. There is a big business in the area — Xanterra, which has the Glacier Park concession contract. It’s owned by billionaire Philip Frederick Anschutz, who also owns oil, railroads, telecommunications and entertainment companies. Safe to say nobody around here has his phone number.

Claire Cheff calls their guide business a calling; it was founded almost 100 years ago by Mark Cheff’s grandparents, a Montana cowboy and a Salish outdoorswoman. Claire Cheff married into the family and loves to watch families reconnect as the mobile phone signals disappear a mile or two up the trail. People panic briefly, and then they start to talk. The trips are an adventurous vacation, but with the side effects of teaching respect for the environment, the importance of land preservation and plain old-fashioned humility. Everyone gets equally sore and dirty on a 10-hour ride in.

Entrepreneurs Do More Than Supply Jobs

Our responses to the pandemic so far have focused on jobs, and small businesses’ role as employers. The Federal Payroll Protection Program (PPP) enabled some small businesses to keep their employees, at least for a time. But it had its limitations – and those limitations hit small businesses especially hard. The next iteration of federal aid will need to have a more powerful focus on the smallest companies in our economy if we’re to have any chance of saving them. These companies need to see an extension of the PPP program – particularly for those who have been hardest hit; a broader set of expenses against which aid money can be spent and still be forgiven; and, importantly, the expenses covered by PPP need to be tax deductible so small businesses don’t face an insurmountable tax burden at the end of the year. A streamlined and clear borrowing and forgiveness process are also critical pieces that should be addressed in new legislation.

Maybe it will spur Congress, state legislatures or private philanthropies to action if we recognize the intangibles slipping away as millions of businesses close. Like many small business owners, the Cheffs exist in a web of other small businesses and are de facto workforce training, sometimes for young men who need nothing so much as a summerlong dose of hard physical work.

And while we think of dynamism and innovation as qualities that belong to mostly or solely high-tech companies – that would be a mistake. The Cheffs and other guides are on the cutting edge of two trends in American outdoor life: adventure sports and lightweight rafting. Inventions go nowhere without businesses to bring them to market. Very often, it’s the small businesses inside and outside of the tech world that do that heavy lifting.

The Complicated Middle Ground

One of the most important roles small businesses play is that they occupy the nuanced, complicated middle ground. In our research, we’ve seen small business owners taking unexpected stands that are outside the norms — or at least, the stereotypes of what the norms are supposed to be. Progressive on one issue, they are conservative on another. The connection isn’t always obvious, until you recognize that their interest lies in the long-term health of their communities.

On any given night on a recent weeklong trip, small business owners gathered around this Western campfire. The conversations between the Cheffs and the Albers, who own a sawyer company called Miller Creek Reforestation, include talk about the loggers who make a living off timber but who also supported the latest wilderness expansion. Everyone celebrates the victory of the Blackfeet Tribe at Badger Two Medicine. There’s also concern for the Montanans being displaced by less expensive immigrant labor — as well as for the labor standards the immigrants work under. COVID is a concern. So is the health of the business community.

There’s worry about the Forest Service budget, but also an idea to apply for a grant to supplement it. It’s not knee-jerk criticism of “politicians.” It’s a recognition that decisions aren’t simple, and that nobody “wins” in a functioning community — the victory is in continuing to coexist.

When we lose small businesses, we take a loss on three incredibly important pieces of America. We lose jobs and on-the-job training. We lose dynamism and innovation. We lose their owners’ voices, as people of economic stature who have a long-term interest in their communities, and ours.

If our country is to heal, it needs small business owners back and engaged, full-strength. They are the backbone of America. We need to save them.

Adapted from The New Builders: Why Women, People of Color and People over 40 Are America’s Economic Future (tentative title), upcoming by Seth Levine and Elizabeth MacBride

With the Federal Government Doing Nothing, Communities Step Up

As a follow up to the OpEds we published in CNBC back in April (To save the US economy, policymakers need to understand small business 101 and Stampede for emergency loans is crushing lenders, putting millions of small businesses at risk), Elizabeth MacBride and I published a third piece today, Communities across America rush to save Main Street as federal relief for small business stalls. In it we talk about the continued failure of the federal government to help small businesses and highlight some encouraging ways that local communities have stepped into the void to help. It’s inspiring but not surprising to see people across the US step up to help businesses stay afloat.

As a follow up to the OpEds we published in CNBC back in April (To save the US economy, policymakers need to understand small business 101 and Stampede for emergency loans is crushing lenders, putting millions of small businesses at risk), Elizabeth MacBride and I published a third piece today, Communities across America rush to save Main Street as federal relief for small business stalls. In it we talk about the continued failure of the federal government to help small businesses and highlight some encouraging ways that local communities have stepped into the void to help. It’s inspiring but not surprising to see people across the US step up to help businesses stay afloat.

I’m disappointed that the Senate stepped away from their negotiations around the additional relief bill. It’s become clear that millions of small businesses have already closed or are just hanging on by a thread. We need to do more to support them and it appears the government is shifting that burden of effort to our local communities which are already stretched too thin. Amongst other things, the OpEd highlights an innovative fund that Colorado has set up to support small businesses, the Energize Colorado Gap Fund. I’m really proud of the work that my partner, Brad Feld, along with Wendy Lea, Mark Nager, and others have done to inject resources into the struggling small businesses in Colorado. But to be clear, those resources should have been supplemental to the support the government was providing to grassroots entrepreneurs. Without the Senate doing the hard work of finding a middle-ground, we’re leaving a majority of our country’s small businesses twisting in the wind. Many of them will not survive until after election day when it’s most likely the Senate will look at passing the next large relief package. I’m hopeful that some additional pressure from constituents will make a difference.

Op-ed: Communities across America rush to save Main Street as federal relief for small business stalls

Last week, the U.S. Senate gave up the fight to save America’s small businesses. They walked away from negotiations that would have extended a lifeline to grass roots entrepreneurs on the front lines of one of the worst economic catastrophes in U.S. history.

But from Colorado to Ohio to Virginia, we have seen communities across the country stepping up where the federal government has failed. As we’ve been researching an upcoming book about the future of entrepreneurship, we have found cities dipping deep into strained budgets, turning to new technological solutions and coming together in creative ways to save their local businesses, lending hands and providing investment dollars to struggling businesses in their communities.

Communities are leading where the Trump administration is failing and as election-year politics freeze Congress into inaction on renewing and simplifying the aid programs passed last spring.

Consider what happened in the small mountain city of Staunton, Virgina. On Aug. 8, a storm cell stalled there, dumping five inches of rain in an hour and 40 minutes. Rivers ran through the downtown, four feet high. Cars went through windows, according to Debbie Irwin, the director of the Staunton Community Creative Fund, an entrepreneurship support organization.

At least 50 small businesses flooded. This after six months of a pandemic assault that has devastated businesses and dragged revenue down by as much as 70% to 80% across this community. The morning of the flood, Irwin started messaging Greg Bean, executive director of the Staunton Downtown Development Association. “What can we do,” she texted.

Within hours, they had organized hundreds of volunteers to carry trash and scoop mud from the storefronts and restaurant floors. Their GoFundMe page, set with a $20,000 goal, surpassed $100,000 within four hours.

“We’ve been relying on the grit and resilience of small business owners,” said Irwin. “I don’t know how much more we can expect from them.”

Even as communities such as Staunton act, they know it won’t be enough.

An economic catastrophe in the making

The probable loss of millions of small businesses over the next six months is an economic catastrophe of historic magnitude. America is home to a lot of big companies that dominate the headlines, mindshare and financial markets of our country. But the real story of American business has always been about small.

Small businesses create two-thirds of net new jobs and are the driving force behind U.S. innovation and competitiveness,” says the SBA, which tracks business trends for the U.S. government. Small businesses accounted for 44% of all economic activity in the United States and were responsible for $5.9 trillion in GDP in 2014, the last year for which data are available.

Small business closures will instantly swell unemployment numbers and put further strain on localities’ budgets. Small business is a broad term and includes an array of companies across the country, and there are some who haven’t been affected or that have benefitted from the pandemic. But what you might think of as “grassroots entrepreneurs” represent by far the greatest number: Restaurants, hair salons, local shops and markets. They’re getting clobbered, and it’s going to get worse as we move from summer into fall and winter and the weather deteriorates.

Some 400 miles away from Staunton, trying to stave off the catastrophe, the city of Akron, Ohio, has given out more than $5 million in direct grants through the CARES Act. More than 90% of the 13,262 employers in Akron in 2018 had fewer than 50 employees, employing as many as 160,000 people. Those establishments likely include some larger restaurants that survived the first wave of the pandemic, but might not survive the winter.

“To permanently lose 20% to 30% of them would be catastrophic,” said James Hardy, the deputy mayor for integrated development by email. “Particularly when you consider that Akron had only recently ‘recovered’ from the Great Recession. Meaning we had returned to pre-recession job numbers.”

Even worse is what happens to the employees. “It would be a gut punch to thousands of local residents and entrepreneurs. One that could send them and their families back for a generation,” Hardy said. “60% of Akron residents live paycheck to paycheck or worse. We know from this and other research that Black and female workers and business owners will continue to be hit the hardest.”

The city is now experimenting with a new app — the city’s version is called Akronite — to promote small businesses and to encourage residents to shop locally. About 2,600 people have signed up so far.

Akron is spending more than $200,000 on the app over two years. Akronites spend money in small businesses to earn “blimpies” (think Goodyear) and redeem the rewards for cash at small businesses.

Hardy expects the investment in the app to pay off in terms of higher spending at local businesses. But the biggest benefit: The small business owners will feel that somebody cares. “They’re scared and frustrated,” he said.

So is he. “I’m choosing my words carefully,” he said. “There is a lack of leadership in Washington, D.C.”

Grassroots relief efforts

A handful of communities are helping small businesses that are willing to sell equity in their companies through local investing platforms, including MainVest, outside Boston, LocalStake, based in Indiana, and Milk Money, based in Vermont. Investors can buy into local businesses for as little as $100, based on business or expansion plans.

But the most important thing communities can do for small businesses now is find some way to get them cold hard cash until there’s a real end to the pandemic. The support can come in the form of grants or – less preferable – low-interest loans and other forms of support to help rebuild their businesses.

When the federal aid programs ended July 31, many localities stepped up to offer support. The city of Staunton, for instance, offered $12,500 grants. Augusta County, Virginia, also offered assistance to its local businesses. Many communities have been taking some of the money from their own CARES Act allocations and instead repurposing it to support businesses in their communities instead, according to Lewis.

But that money is quickly depleted. In Colorado, an innovative statewide loan program called The Gap Fund began offering grants and loans to Colorado businesses with fewer than 25 employees. Launched with $25 million raised from public and private sources, the fund received almost 1,500 applications in its first 24 hours. The average funding request was $24,000. It’s a great start, but clearly the need is many times the capacity of its current resources.

“The most important thing communities can do for small businesses now is find some way to get them cold hard cash until there’s a real end to the pandemic. The support can come in the form of grants or – less preferable – low-interest loans and other forms of support to help rebuild their businesses.”

Back in Staunton, nearly 90% of the businesses affected by flooding in August have re-opened their doors, Irwin said. A handful of businesses have closed since the pandemic started, including a loved bookstore, and two restaurants. “We’re going to lose more,” she said.

In Staunton, small businesses are the heart of the small city and they are the gathering places and the vehicles for people to connect. “We are Zoomed out. We are technolog-ied out,” Irwin said. “During the flood, you saw what happens when people prioritize community over their own interests.”

America’s losses will be incalculable if the next six months go as we expect them to. One recently released working paper by economist Robert Fairlie suggested that the number of businesses in the United States fell by 22% — 3.3 million businesses — between February and April of this year. Not surprisingly, this was the largest drop ever recorded. And that was just in the initial months of the pandemic. We’re bracing for a fall surge that could devastate America.

Our leaders can learn something from what’s taking place in communities across our country. Citizens are stepping up to save their Main Streets because they understand how important our local businesses are to the fabric of America. It’s time for Republicans and Democrats in Congress to put aside their differences and act.

Work Lessons from the Pandemic

I’ve been thinking a lot about what changes in my work I’d like to keep, post-pandemic (can we even talk about a post-pandemic world? It still feels pretty far off). I’m trying to be deliberate and actionable about it. For me that means actually writing down what I’m trying to change and why. It also means trying to dig deeper than top level or cliche ideas (i.e., of course I’d like to travel less; but the deliberate and actionable version of that idea addresses the drivers of my travel – for example board meetings – and specific ways I’d like to change what’s pulling me out of town). In my world, the two biggest things I’ve changed are:

- Have completely unscheduled days. My world gets easily overrun with meetings (I’m sure yours does as well). For the last few months I’ve been experimenting with having at least one day a week that is completely unscheduled. I block it off on my calendar, don’t allow anything to creep in, and am super stubborn about keeping it that way. I use this time for work that requires deeper thinking, for writing and for outbound calls. Sounds simple, but it’s been incredibly powerful. In my ideal world, I would have 3 days a week for scheduled meetings and 2 days that are blocked for work. I’m still building up to that. An interesting side note here is that adjusting my schedule in this way quickly fills the other 3 days of my week, which has forced me to be even more careful about what I let on my schedule.

- Have a stated purpose for every meeting. It’s easy to let meetings slip onto the calendar and, like you, I struggle with the right balance of availability vs sanity in my calendar. One of the things I’ve done to try to alleviate meeting overload is to be sure that I have a clear, stated purpose for every meeting. That helps me better decide whether it’s a meeting that makes sense to schedule, or whether it’s actually something that can be handled in some other fashion. In my world, handling it in “some other fashion” means either over email, Voxer or with a call (but where that call happens unscheduled, on one of my unscheduled days). Like many people I’m often too quick to suggest setting up a scheduled meeting (now Zoom). In the immediate moment doing so saves time, but in the long run, of course, it’s not very efficient or helpful.

I recently asked a group of about 18 CEOs I work with regularly their thoughts on this. Below are a few things that they identified that they implemented during Covid for their companies that they’d like to continue that I thought were worth passing along.

- All employee office hours. This is time set aside on a quarterly or monthly basis for employees where the CEO hangs out on an open Zoom call and anyone can pop in to talk one on one, ask questions, present ideas, voice concerns, etc. This has been particularly helpful in getting feedback from quieter employees who don’t always speak out in group meetings.

- Deep dives on specific areas of the business. This one is pretty self explanatory but a number of CEOs I work with are using the extra time they’ve gained not commuting and not traveling to get more personally involved in specific areas of their business. Product was cited more often, but some were jumping into sales or marketing as well, and one even referenced finance as an area they were going deep in.

- Getting expert at hiring and managing remote employees. Pretty obvious, given how businesses are operating in this time. But in my framework, the key here is to go deeper. Saying you want to be open to remote employees is fine, but for this exercise, the important part is to understand as a business what practices you’re going to change to enable that. This will vary from company to company but several I work with have set up cross-functional task forces to help come up with ideas for how to more efficiently operate/what practices to change to enable and promote remote work across the business.

- Daily all-company stand ups. This was something implemented by both larger and smaller businesses (many small companies do this but eventually get away from it – I think Zoom culture has enabled it to come back, even in larger businesses). Be careful on this one as it can be a real time sink for your company, but as a quick 5 minute daily check-in, several CEOs I talked to found it a helpful way to keep employees engaged and on the same page.

- A focus on mental fitness. We’ve been recommending Meru Health (a Foundry portfolio company) to internal Foundry employees as well as our portfolio, and many have found their system really helpful. Generally speaking, CEOs have found that Covid has given them an opportunity to work more on their both mental and physical health giving them more headspace to deal with the daily crises that spring up. Several are finding creative ways to help encourage that across their employee base (team contests around steps, virtual company 5Ks, a focus on mental as well as physical fitness, etc).

- More frequent employee reviews and organizational changes. Several CEOs referenced a realization that they realized through needing to reduce costs that they had over-invested in areas of their business and talked about the desire to more regularly do a more wholistic review of their organizations and where they were directing resources to be more agile about repositioning resources and people. In some cases this would mean parting ways with employees whose job functions were no longer needed. In others it might mean repositioning employees to new roles. It’s a hard thing to talk about but making this an ongoing process rather than something that requires a forcing function (finances getting tight, global pandemic, etc.), building it into a business as a regular work-flow was a key take-away for several I talked to.

There were a number of other ideas that came out of this discussion but these are some of the key ones. If you have additional thoughts, please add them below in the comments.

Performance-based Options Grants

I had a bunch of interesting comments on my recent post about company options programs – many very constructive. One of the things a number of people have asked was what I think is the right approach to performance-based options grants. I realized I referenced this in my original post but didn’t cover it in any detail.

Performance grants are important and provide an opportunity to describe a nuance that I didn’t do a very good job of outlining in my original article. For performance grants, I believe the right methodology is for the board and the management team to decide on a pool of options that is available in any given year for merit-based grants. I think it’s important that the company concentrate those grants on the absolute best performers in their business. I’m not a fan of a large percentage of employees getting performance-based grants nor am I a fan of grants being formulaic based on comp or similar factors (i.e.,not really based on performance). I believe that performance grants should be concentrated on the absolute top end of the business (the top 5%… maybe top 10% of the company). The point is to reward your absolute best performers, not to have your performance grant program work as a company-wide option top-up every year. From my perspective, diluting their effect by giving them too far down the employee line is counterproductive.

The nuance that I didn’t describe in my last post is that it’s important to realize that you can deviate from the formula, up or down, based on your belief of the importance or the performance of the options recipient. In theory, if you’re doing a good job of performance grants, your absolute best performers will end up with more options than your average employee in the same role. Using the refresh formula I outlined in my previous post will provide them with incremental options in their refresh as well, as it should. That said, it’s important to take a look at the refresh amounts and do a sanity check to make sure that they map. I would not recommend varying widely from this but, as Chris Moody pushed on in one of the comments to that post, being a slave to a formula is rarely a good idea in anything you do in your business.

Ok – enough about options for now. Hopefully these posts have been interesting and helpful.

Options about your Options – How to think through your company’s option program

Quick break from Covid related topics for a moment to post something I’ve been intending to write about for a few months but haven’t had the chance to commit to paper. It’s perhaps a boring topic – Options and your company’s option program – but an important one.

Quick break from Covid related topics for a moment to post something I’ve been intending to write about for a few months but haven’t had the chance to commit to paper. It’s perhaps a boring topic – Options and your company’s option program – but an important one.

Despite how much time companies talk about the importance of their employees and, in many cases, how every employee is also an “owner” of their business through their option program, most companies are pretty ad hoc (or down right sloppy) about how they plan for and execute their option program. My hope with this post is to push your thinking around options and encourage you to formalize what you’re doing into an actual option program.

Side note before we jump in. I’m not giving any tax or legal advice here. You have accountants and lawyers for that – be sure to check with them. I’m also not going to give option bands for various positions. The data change over time and, frankly, I’m less interested in debating what % grant your Director of Product Management should receive given your stage of company and capital raised, and more interested in the structure of your program.

Why have an option program to begin with? It strikes me that many founders never really consider this question. That’s a mistake because knowing what’s driving your desire to give out options will inform how you think about your option program. Many founders feel that it’s equitable to have everyone share in the upside and feel like owners. Some feel that, especially for early employees, options should act as a reward for taking startup risk. Many startups use option packages to compete with the larger current comp packages of bigger, more established businesses. Yet others try to use cash to minimize dilution for early employees and try to rapidly reduce their reliance on options. All good, but different philosophies (and different markets and market conditions) can lead to different initial option programs. One thing not always acknowledged is that often option programs are intended to be mercenary in nature – binding employees to the company through the disincentive of needing to exercise their options (and in some cases pay tax on the paper gain) if they leave. What your value system looks like and why you’re setting up an option program can and should have ramifications on how you set up your option program. No value judgments here – my goal for you is to be deliberate about why you’re giving employees options and to align the details of your program with what you’re trying to get out of it.

Should everyone in my company have options? The answer to this should follow from the answer to why you’re setting up an option program in the first place (and can potentially change over time as you grow your business). Many, but not all, Foundry companies give options to all their employees. Often this is due initially because founders feel that it’s “right” for all employees to have some ownership (or right to ownership) in the business. Others feel less strongly about it and either don’t distribute options below a certain level of employee (say manager level) or have programs where employees need to be at a business for a period of time before they earn the right to have an option grant. Obviously, there are competitive considerations to think about, but in some markets, options are either not well understood, aren’t expected as part of an employment package, or aren’t commonly given to employees below a certain level. Take a moment to decide whether you feel that everyone in your company should have the potential to be an owner and what’s driving your thinking about why.

Using options in lieu of compensation. It is very common for companies – especially companies early in their lifecycles – to try to use options to reduce the total cash outlay over time. That’s ok, but there are a few things to keep in mind if you’re doing to do this. The first is to be deliberate about it if you’re going to do it. By that I mean pick a “value” for each option and formulaically apply that to decrease comp. This option value can change over time (your company grows, raises more money, and reduces overall risk, etc.) but if you’re going to use options this way be methodical about it. We’re going to talk about setting deliberate option bands for various levels in your company in a second and the starting point for options should be those bands. From those your offer to an employee can methodically (meaning formulaically) reduce cash and add options. I’ve sometimes seen companies make offers with a range of salary and options – making explicit the trade-off they are offering between cash compensation and options. It’s important to recognize that not all employees will value options in the same way (or be in a position to trade cash comp for options). It’s also important not to go crazy with the trade-off. For starters, it can lead to inconsistencies in comp that are too large to sustain over time. But it will also change the nature of your workforce if you only hire employees that can work for well below market cash comp. Both of those things are not good for your business, so while it’s ok to offer some level of cash/equity trade-off, it shouldn’t be over-done. It’s also my experience that as companies grow they seek to normalize both cash and equity compensation over time, leading to some inconsistencies in how early employees are treated (cash comp tends to come up more quickly than equity comp so if you’re not careful you’ll further disadvantage early employees who took larger initial cash compensation – this is both not fair and can be discriminatory). So use this tool judiciously and over time as you have greater cash resources, it should be reduced or eliminated.

Create option “bands”. Every company should create a schedule of new hire grants for each level position in their business. This schedule should lay out the range of options that you’re targeting for each position in your business. This exercise should be done annually and reviewed with the board (and/or compensation committee of the board if you have one of those). This will help do a few important things including setting appropriate expectations with your board about equity comp, ensure that you’re not making ad hoc compensation decisions, avoid various forms of bias in the hiring process around granting equity and allow you to quickly and seamlessly get option approval from your board. This will also force good conversations about outliers and, in my experience, tends to be a deterrent to title inflation, which I hate. In summary, don’t be ad hoc about options – be methodical about them.

Option Exercise. Typical option plans allow employees only 90 days to exercise their options once they leave a company. This can be a real incentive for employees to stay at a business, as there are often meaningful tax consequences to exercising options upon leaving (again, I’m not giving tax advice; this is actually something I’d like to see changed in the tax code. More complicated than I want to dive into here, but it would actually benefit employees and also the federal coffers as the tax would get paid on greater gains when the stock is eventually sold. And it would be the more fair thing to do, but I digress). Interestingly, there was a move a few years ago to extend the option exercise period after an employee left to a much longer window – say 7 to 10 years. Pinterest, Kickstarter and a handful of other relatively high profile companies did this. I suppose the idea was that it was an employment perk – like a better healthcare package or free lunch. At the time I had mixed feelings about it and I still do. Options have value because of their optionality – at some point in the future they may become worth a lot of money, but so long as you stay employed by your company, you don’t have to invest (purchase your options) and essentially get a free ride on the potential upside. Something about continuing that free optionality (essentially at the expense of other employees who stay at the firm) feels off to me. But, I know others disagree, and ultimately the choice here relates to your goals for your option program, your personal views about equity ownership and participation and your thoughts on fairness (which could swing this either way). But better to have a view on this that is deliberate. If you don’t say anything about it to your lawyers, your option plan will almost certainly have a 90 day exercise window.

Option Refresh. Even companies that are methodical about their option program set-up often skip this key element of a successful option program. I think it’s a super interesting (and important) part of that program and have put quite a bit of thought into how to best structure time based refreshes to employees. My background thesis inherent in this is that employees with options should continue to vest new option as they continue to work for your business. I think this is both practical and fair.

Here is an idea for what an option refresh package should look like:

- At an employee’s 3rd anniversary, give them a new grant equal to the greater of a) 25-33% of their existing option grant; or b) 25-33% of what a new employee hired for that position today would receive.

- The grant would begin vesting on the employee’s 4th anniversary and will vest monthly over 4 years.

This formula works pretty much across the board, with the exception of founders, who need to be considered differently (founders with meaningful ownership typically are not included in refresh grants). To be clear, what I’m describing here is separate from promotion grants and from annual or semi-annual performance related grants (which I think of as more a part of a company’s compensation policy than their Option policy).

Hopefully this post will give you some ideas for how to best structure your own option program. I’ll be interested to see your feedback either below in the comments or directly to me.

Better Zoom Meetings

My partners and I hold weekly Monday meetings and about once a quarter, we do an extended, six or seven-hour version. Before COVID-19, we’d end the day with a dinner and a chance to socialize and decompress after a long day of portfolio updates and strategic planning. And, of course, before COVID we’d all be in person. Our discussions were lively, they were engaged and we’d often make use of whiteboards, sticky notes and other forms of interaction (we have a post card with a logo for each of our portfolio companies which we often make creative use of). They’re fun and super productive.

My partners and I hold weekly Monday meetings and about once a quarter, we do an extended, six or seven-hour version. Before COVID-19, we’d end the day with a dinner and a chance to socialize and decompress after a long day of portfolio updates and strategic planning. And, of course, before COVID we’d all be in person. Our discussions were lively, they were engaged and we’d often make use of whiteboards, sticky notes and other forms of interaction (we have a post card with a logo for each of our portfolio companies which we often make creative use of). They’re fun and super productive.

And then COVID hit and our meetings lost their soul (and their fun, and their interest, and – to be frank – some of their effectiveness). I wrote about my frustration of trying to hold “strategic” meetings (vs tactical ones) over Zoom a few weeks ago. Since then I’ve gotten a bunch of helpful feedback and I’ve spent time researching ideas for how to make these sorts of meetings more effective and productive. Here are a few of the things that I learned (and that we implemented at Foundry in our most recent “extended Monday” meeting this week). I’d love to hear other ideas and will update this post accordingly.

- Prework. We often have some amount of pre-work for meetings but its even more important, I think, to prepare ahead of time for Zoom meetings. It’s also an opportunity to use the meeting for more conversational topics rather than reporting (see below), which can drag on in a Zoom. A brief exercise ahead of the meeting gets people thinking about the agenda and ready to jump in when the meeting starts.

- The agenda order matters a lot. In thinking through the ordering of the agenda, put deep discussion items first. Unlike in person meetings where it’s sometimes helpful to ease into the meeting with some lighter topics, Zoom meetings are most engaged when people are fresh. Best to have the meatier items up front and save the end of the day for more informational topics. We also used the pre-work for this – pre-meeting exercises that resulted in update-style content being created (and then consumed) ahead of time so we didn’t have to spend Zoom time doing it.

- A quick green/yellow/red check-in can be very helpful. I like starting most of my meetings this way – a quick stoplight check-in so everyone knows what frame of mind everyone else is in. It’s even more important over Zoom where some of the subtle cues of a person’s emotional state are easily missed. I have some meetings where people just put this in their Zoom name so everyone can see it in the chat (i.e., this doesn’t have to take up a ton of time). I also like starting longer meetings with a few deep breaths (10 works) so everyone can get in the present and clear their heads before jumping in.

- Timed breaks versus topic breaks; frequent breaks. This is an important one. Zoom fatigue is real. Other than keeping meetings relatively short (hard for strategic meetings) one of the best things you can do to stay fresh is to take relatively frequent breaks. I like every hour to 90 minutes for longer meetings. And, importantly, these should be time based, not topic based. Have the discipline to stop mid-topic to take breaks as scheduled, rather than trying to power through them with a break as the “carrot” at the end (leads to rushed, incomplete discussions.

- In-meeting engagement. Find ways for people to stay focused and engaged. Some kind of feedback task can be really helpful for this. For our last meeting, we went old-school with sticky notes to replace the usual whiteboard, and asking people to share feedback after each session. Zoom is starting to roll out some in-meeting collaborative apps. Tools like Miro, Lucidchart, and Stormboard are things I’m looking at.

- Use grid view; stay off mute. Looking at and listening to one person for an extended time gets dull quickly. Allowing everyone to see and talk to each other at the same time help mimics an in-person meeting better and allows everyone to stay engaged. Having everyone stay off mute encourages engagement and keeps people off email.

- Second screen for shared docs. The screen share feature on Zoom is fine, but it makes it harder to see everyone who is on the call. If it’s possible, try to have people look at shared docs on a separate device. If you have to screen share, keep it short and pop back to the grid view/no share frequently.

We implemented all of these ideas at our last Foundry meeting and it was much, much better. More engagement, more fun and we got much more done. It also allowed us to limit the meeting time (although it was still 5 hours, which is definitely the outer limit for Zoom meetings). Still not the same as in person but better. We’ll keep trying to improve.