The Profit Imperative

With the markets crashing around us and the sky once again falling I thought it was time to revisit a few fundamentals and perhaps more importantly share some what what we’re now seeing in the private funding markets.

Growing Profitably. Let’s start with what I labeled the Growth Imperative a few months ago in a post, where I pointed out 1) that investors were (over) valuing growth and 2) that when this changed it was going to change quickly (and in a separate post said: “when the growth imperative shifts to a profit focus, companies with high burn and weak operating metrics can get stuck in the lurch.”). It always amazes me how quickly the markets can shift and how rapidly investors change their mind set. But they do, and they are right now. We’re seeing lots of market data points that suggest that the private markets have shifted dramatically to a Profit Imperative, overnight eschewing high growth/high burn with no line of site to profitability and favoring companies that are growing more slowly but doing so profitability or with a clear path to profitability. There’s an increased focus on key metrics – especially those core metrics that drive the spend/growth curve such as LTV/CAC and months to pay back CAC.

Valuations are Down. As the public markets have fallen, so have the private markets. No surprise here, but the drop has been rapid and it’s been dramatic. In the public markets public SaaS valuations (EV/Revenue) are down 33% since January and 66% since their high in January 2014. This is true across other markets and has quickly worked its way down into the private markets (btw, the current EV/Rev multiple for public SaaS is 3.2x). Different sectors of the market have seen varying levels of decline, but overall the private markets are off similarly to the public markets. I’d point out that this is especially true for companies in the Series B stage.

Flight to Quality. Just as we’ve seen this in the public markets (with Google, Facebook and a few other giants suffering stock losses much less than their smaller peers), the private markets are quickly differentiating true market leaders from the rest of the pack. And while there are plenty of markets that aren’t necessarily winner take all, investors aren’t buying the story for why a 2nd or 3rd player can break out.

Product vs. Company. There seems to be a growing realization – especially in the B2B SaaS market, but also across others – that many of the companies that have been funded and have seen reasonable growth are really products, not companies. And that at some point their growth will flatten out as their product saturates the market. I think this is coming through in subtle ways as investors evaluate companies (I’m not hearing people talk about it explicitly) but behind some of the comments is clearly this question and all companies that are in the market to raise capital should recognize this bias.

There’s no silver lining with which to end this post (other than that I personally think the markets – public and private – are overreacting; but that doesn’t mean they’ll necessarily correct back any time soon). Hopefully you took the opportunity in the past few quarters to shore up your balance sheet. If you didn’t it’s time to be careful. Plenty of companies will continue to get funding, but beware of the market dynamics that I describe above.

Introducing Foundry Group Next

This was also posted on Brad Feld’s blog and a similar announcement is up on foundrygroup.com as well.

Over the years at Foundry Group we’ve built an extensive network of companies. While we’ve invested in some of these directly, this actually represents the smallest set of companies that we are involved with. We have also invested indirectly in many others through our investment in Techstars. Yet another, and much larger set of companies, come from our investments in other venture funds.

In 2013, we started thinking hard about the future of Foundry Group. When we started Foundry in 2006 we were very clear that we were not going to build a legacy firm. There would be no generational planning, no transitions to younger partners, and no senior partner hold-outs who would hang onto economics well after they had stopped working. Simply put, when we are done investing, we will drop the mic and shut off the lights.

During these discussions, we reflected on the incredible collection of early stage VC firms we’ve invested in personally over the years. We’ve been investing as individuals in venture firms going back almost 20 years. The four of us have served as mentors, and in a number of cases, formal advisors to funds around the world. In 2010 we started making the majority of our fund investments together through a common entity. While we never thought hard about this activity, over the years we’ve amassed a very strong track record through these fund investments. It’s also been fun – a great way to get close to new managers, build lasting personal relationships, and see deal flow for our Foundry Group investing activity.

In late 2014 the four of us got together to talk formally about the future of Foundry Group. We had each taken a month off in 2014 – well needed breaks after what had been a seven year sprint since starting Foundry Group. We were clear at that point that we wanted to continue to make early stage investments through a new Foundry Group fund, which we subsequently raised in the middle of 2015 and started investing at the end of the year.

At the same time we discussed our later stage investment strategy. In 2013 we raised a fund called Foundry Group Select. The strategy behind Select is to make late stage investments into successful companies where our early-stage funds had previously invested. The strategy has been a good one and with two early exits (Gnip and Fitbit) we’ve already returned significant capital.

As a result of our extensive networks, we constantly see other potential late stage investments. We’ve stayed away from these investments, not because they aren’t interesting, but because with the Select fund strategy we had limited ourselves to investing in existing Foundry portfolio companies. We broke this rule recently to make an investment in AvidXchange, a business run by an entrepreneur who I have known for over 20 years. The conversation around AvidXchange brought to light the magnitude of the opportunity we have to invest in interesting companies outside of our early stage portfolio.

We also had a long conversation about our GP fund investing strategy. It is clear to us that we enjoy investing in other VC funds and working to support the GPs. When we looked carefully at our track record, it became clear to us how lucrative this activity has been.

As we discussed the confluence of our fund investing strategy, our current Select strategy, and our interest in acting on our unique later stage deal flow, we realized that there was an opportunity to wrap these three ideas together into a single entity that would encompass not just what we had previously called our Select strategy but would also institutionalize our fund investment strategy as well as leverage those and other relationships to invest in other later stage opportunities in our broader network.

The critical ingredient for bringing this all together was finding the person to help us execute our GP fund strategy. Fortunately we knew exactly who we wanted to work on this project.

For the past 13 years, Lindel Eakman has been the head of UTIMCO’s private equity group. He’s created an incredible portfolio of investments in venture capital funds, including Union Square Ventures, Spark Capital, True Ventures, IA Ventures, Techstars Ventures, and Foundry Group. In April 2007, Lindel committed to be our largest investor in our first fund in 2007, taking 20% of the fund. This was a bold move, as we only had one commitment at the time.

Lindel – through UTIMCO – has continued to be our largest investor. He has been on our advisory board and for the past eight years has been a key advisor to us. Over the years he also has become a close friend.

We’ve been discussing this strategy with Lindel for most of the last year and have started calling the initiative “Foundry Group Next”. The Next strategy will not only allow us to continue making direct investments in high-potential startups, but will also scale-up our ability to support venture firms and funds whose vision and values align with ours. Through this activity, we hope to spread the Foundry Group values and DNA further into the overall venture and startup ecosystem.

We are pleased to welcome Lindel to Foundry Group Next and are excited to start this new chapter with him. And to make the the lawyers in our lives happy, we need to say that in no way is this blog post an offer to sell securities or an advertisement of us raising a new fund. We have yet to announce anything regarding any new funds that we may raise in the future.

Boulder needs to VOTE NO on 300 and 301

Below is from a post we just put up on the Foundry blog. It’s critical in this election that the business community in Boulder takes a stand for progress and against closing the doors to the city. The two issues below are of great importance to the city of Boulder. So is electing a strong and reasoned City Council. I’m supportive of OpenBoulder’s approach to that and they have great information on the candidates they’re backing. In particular I’ve been helping my friend Bill Rigler with his campaign and would encourage you to be sure to include him as you vote. He’s a thoughtful, progressive leader who will bring great energy and mindfulness to our city.

This year’s local election in Boulder is a critical one. The city that we love risks shutting its doors. While the business community in Boulder has contributed immeasurably to the vibrancy, charitable contribution base, economic development, and success of our community, there is a faction in Boulder that feels that our city should stop moving forward and instead should live in the past. This faction believes in a less inclusive Boulder and aims to achieve this goal by literally shutting the doors to our city.

This is what is behind propositions 300 and 301 which are proposed amendments to the city’s charter.

This faction is well organized and well funded and the slogans make it sound reasonable. But make no mistake: the goal is to immediately freeze all development of all types around the city by enveloping the city a bundle of political red tape.

In the coming days, Boulder residents will be asked to vote on the following:

#300 – Neighborhood Right to Vote on Land Use Regulation

#301 – New Development Shall Pay Its Own Way

These initiatives must be voted down.

While innocuous sounding, the names of these initiatives completely misrepresent their intent and the dire consequences that would result if they are enacted. The truth is that neighborhoods already do have a say in projects that affect them, and developers already do pay some of the highest fees and taxes in the country.

Effectively, these proposals will create 60+ neighborhoods in Boulder. Can you imagine what would happen if we had that many homeowner associations that had the power to hold special elections and veto land use changes approved by city council? The smallest of those neighborhoods would be comprised of just 19 houses. That’s not “local control” (which already exists), that’s a deliberate attempt to create gridlock.

These initiatives will immediately freeze important infill development, including affordable housing, transit-oriented development, neighborhood serving retail, social service centers, and day care centers. The city manager has stated that the city will stop issuing permits of any kind for at least six months while they figure out what these initiatives mean and how to implement them. Once they do start reissuing permits, these initiatives will force the city to levy such high taxes and fees that development will effectively stop in Boulder. This will stop our city in its tracks and greatly exacerbate an already expensive housing market.

These measures are opposed by six former mayors, all nine City Council members, numerous former city council members, Boulder Housing Partners, The Daily Camera, and numerous civic groups like Open Boulder, the Boulder Chamber, Better Boulder, and others. Open Boulder executive director Andy Schultheiss has called them “among the worst pieces of public policy I’ve seen in almost 25 years of observing and participating in local policy-making.”

It’s critically important that we defeat these measures. To do that we need to get the word out to those in our community who want Boulder to continue to be a vibrant city. The sad irony is that those promoting these measures have the time and organization to put towards pressing their backward and closed agenda while many who oppose it are busy helping keep Boulder prosperous by creating jobs and economic growth.

This is a battle we can’t afford to lose. Please take a minute to help us get the word out. Send it to your friends via email and social media. Urge your neighbors to vote and make sure you vote yourself. With ballots mailed out this week many in our community will be voting in the next seven days (over 50% of ballots are returned within a week of their being sent out).

#keepboulderopen

Seth, Jason, Brad, Ryan

_______

Below are some suggested tweets or Facebook posts should you chose to share them:

Click to Tweet: i agree with @foundrygroup. 300 and 301 will have devastating effects on boulder. VOTE NO on both! #keepboulderopen http://bit.ly/1RdPv4K

Click to Tweet: i stand for keeping the doors to boulder open. VOTE NO on 300 and 301. #keepboulderopen http://bit.ly/1RdPv4K

Click to Tweet: in boulder’s upcoming election we’ll decide if we want to live in the past or continue to thrive. #keepboulderopen http://bit.ly/1RdPv4K

This may not be the bubble you’re looking for

At great risk of wading into a debate where there’s no winning, I thought I’d present a few pieces of data that suggest that we’re not exactly in a market bubble right now. Massive caveat here: I’m not trying to predict the stock market. I’m just following my own advice. Plus I agree with my partner Brad, who said recently, “I think everyone will have an opinion and no one will have any real idea,” about what’s going to happen in the stock market (this in an article that appeared after just two days of a down market). But the data are important, so let’s at least pay attention to what’s actually going on. From there you can form your own opinion.

Thought 1: What happens in China isn’t all that important to the US stock market, according to the best investment apps UK has reports on. From some of the reporting you’d think that the US and Chinese markets are tied at the hip. They’re not. Not even close. For sure, the US is a huge importer of Chinese goods. But a weaker Yuan just increases our buying power. Yes – China is a large trading partner, but if you look at its effects on the overall US market, we’re not likely to see a large, near-term effect from a drop in either the Chinese stock market or their currency.

Thought 2: August is historically a volatile month. Maybe it’s the Hamptons air traders are breathing while on vacation in August, but for whatever reason, August tends to be volatile. And 4 of the last 5 Augusts have been down months (despite an overall strong market environment). Of course the only month historically more volatile than August is September, so the wild ride may not be over (to say nothing of the FOMC decision coming up, which will move markets no matter what they decide to do).

Thought 3: The TED spread is still reasonable. This is an interesting one to watch. The TED spread measures the difference between the 3-month LIBOR and the 3-month T-bill. It’s important because a rising TED spread has actually been a pretty good indicator of a US market that’s about to fall. The first graph below shows this – you can see big spikes in the spread leading up to the 2000 market collapse and the 2008 market collapse (the spread continues through each of those two events, but the initial rise pre-dated the markets falling; btw, this also occurred before the ’87 crash). To be sure, the markets can fall when the TED spread is inside of 50bp (considered the top end of the “safe” range). But large market disruptions are typically proceeded by a spike in the TED. It’s rising a bit (see chart 2 below which shows a close-up of more recent TED activity) but is still well within a reasonable range. I’ve also included the VIX index in the charts below to show that volatility isn’t always connected with an increasing TED spread.

So there you have it. At least three pieces of data worth considering when thinking about the current market environment. All this doesn’t mean that you should ignore the current markets. Certainly volatility can lead to uncertainty in both the public and private markets. And as I wrote about last week, when the growth imperative shifts to a profit focus, companies with high burn and weak operating metrics can get stuck in the lurch. But in my view, it’s always a good time to shore up your balance sheet and watch your key metrics. After all, that’s table stakes for running a successful business.

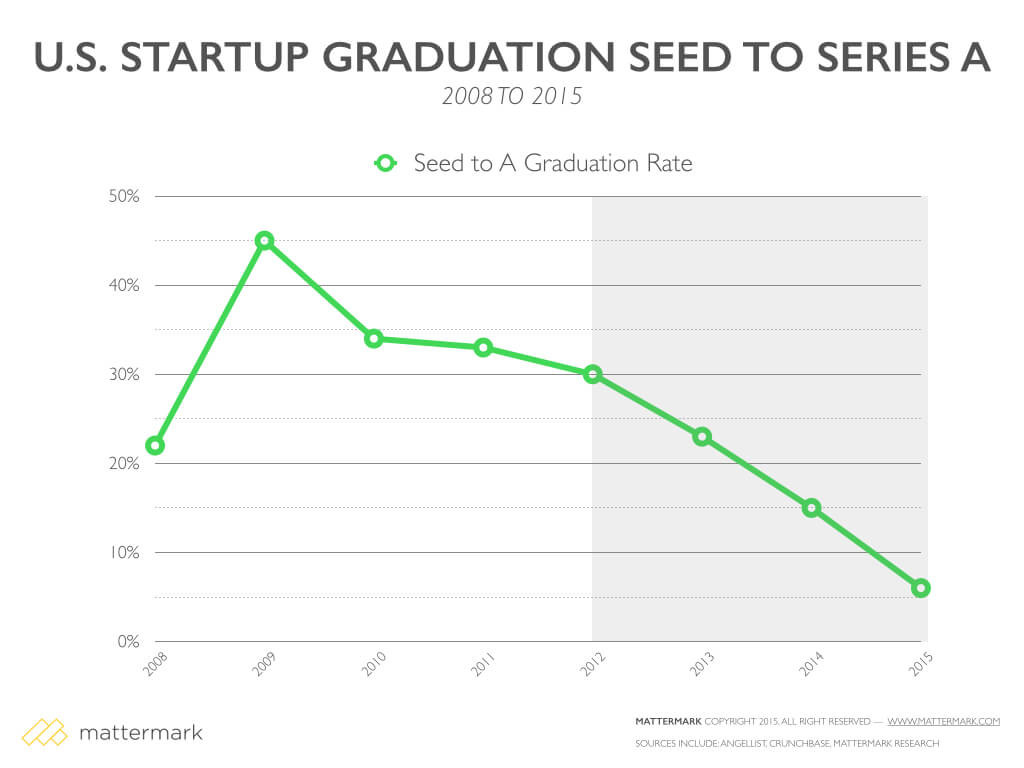

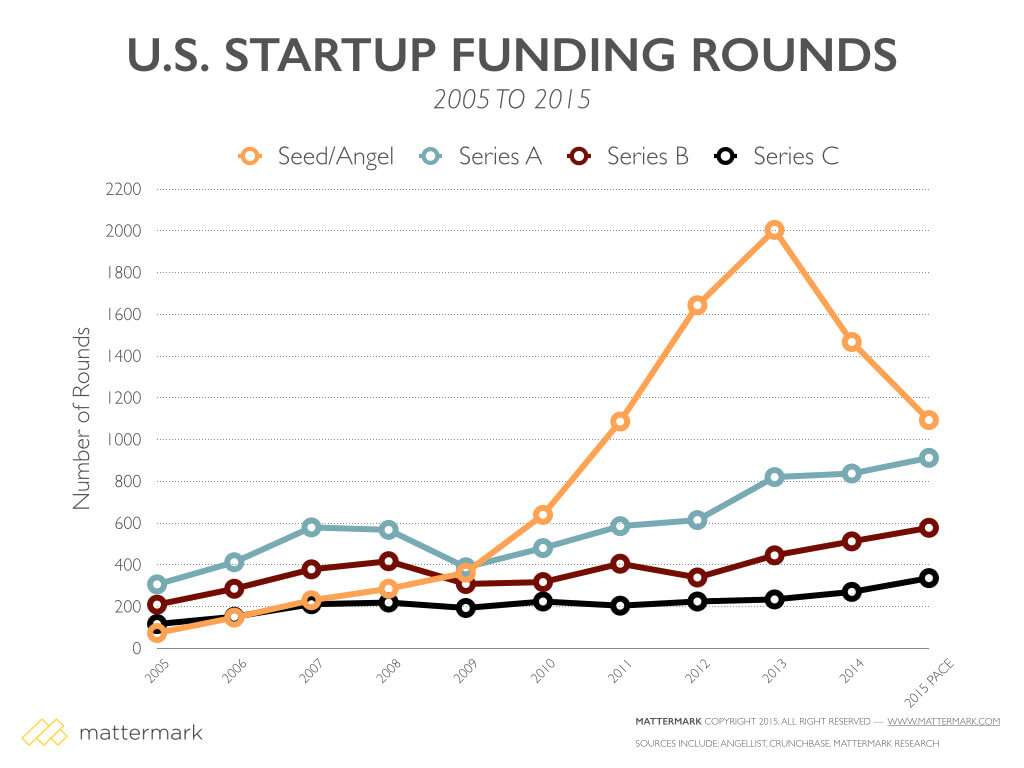

Charts of the Day – The complexity of raising Series A

The charts of the day comes from a new Mattermark report on the current pace of financing. Both relate to the pace of seed funding in the US and the challenge of raising Series A financing. The first chart shows the pace of deals (measured by number of rounds) by category:

Pretty hard to miss the huge blip in Seed/Angel deals in 2013 (but really from 2011 and continuing through 2015, with a peak at 2013). Most of you already knew this intuitively, but seeing it in black and white (at least for me) was eye opening. And while there are more Series A deals being done every year, they’re not even coming close to keeping up with the pace of Seed deals. From an ecosystem perspective this is both what you’d expect and ultimately a good thing. We’ve certainly seen markets where too many companies passed through each funding stage and ultimately that had terrible consequences for the market, for investors and for founders. The best markets are those that are acting rationally and efficiently. We may even be running a bit hot from that perspective (subject of a different, upcoming post, by the way). From the perspective of a Seed funded founder, this should be a clear warning sign that it’s not going to be easy to raise your Series A. In fact, if you look at the trend line of Seed companies “graduating” to Series A, you can see in stark relief the challenge ahead of you’re a Seed funded founder.

We’re clearly seeing this here at Foundry. Our deal flow is always pretty robust, it feels off the charts right now. The number of things that we’re turning down that are interesting, have solid traction and that will ultimately get funded (or should be funded) is unprecedented. I think that’s a direct reflection of the trend described in the charts below. Lots of companies raised Seed rounds, many performed solidly in their seed period and there are a large number of Series A opportunities in the market right now.

There’s no easy advice here if you’re a founder looking to raise your Series A. Obviously, start with building a great business and stand out because of your metrics. But that won’t be true of every business – many good ideas take time to develop market traction. So it’s important to recognize that in the current environment there’s a ton of competition and you’ll need to design your financing process with that in mind (be deliberate in who you target, make sure you’re showing exactly where you’re outpacing the rest of the market, build a larger list of prospective investors, etc.).

The growth imperative (but beware)

First off, a note of apology. It’s been months since I’ve posed here. Not for lack of desire – more about some combination of crazy busyness and lack of proper prioritization. I miss it and am going to try to step it up.

This is a post about the importance of growth, about the current market environment and a note of caution if the growth imperative changes rapidly to the profitability imperative.

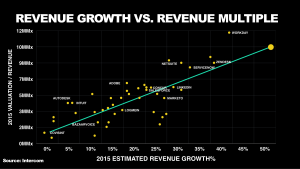

A few months ago we held a “SaaS Summit” for about 130 people from across the Foundry Group portfolio. It was a great chance to compare notes, meet far flung colleagues (“cousins” as we sometimes refer to employees at different portfolio companies) and discuss a variety of topics effecting companies selling with a recurring revenue model. As the organizer of the event I pulled together the morning briefing to kick things off – basically a bunch of data from a variety of different sources talking about the state of the SaaS markets. There was some juicy stuff in there, but one set of facts clearly stood above the rest. At the moment, growth is THE single most important factor when considering the value of a SaaS company. Let’s start with some data and then we’ll parse through what it means.

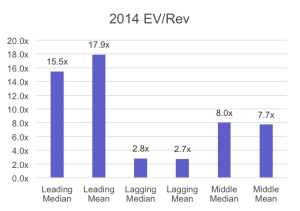

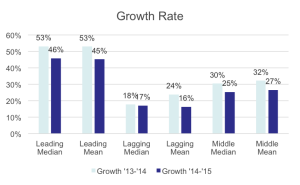

The data below are a mix of things I came up with as well as a some key data points borrowed from my friends at FirstMark, who undertook an extensive analysis of the SaaS market. The full methodology here isn’t worth stepping through in detail, but essentially what the study did was try to separate companies into “leading”, “lagging” and “middle” SaaS companies. This was a reflection of their trading behavior, not an assessment of their underlying business (i.e., we relied on the market for the determination of leading vs. lagging). It’s important to note that there weren’t material differences in revenue size, geography, target market, etc. between these companies.

First the cold hard trading facts. “Leading” companies trade at significantly higher multiples than their peers.

No huge surprise there – that’s pretty much the definition (in this study) for a “leading” company. But helpful to show the stark difference.

So what causes this massive difference? We looked at a bunch of different factors, but as I give away above, the single most important factor for valuation of a SaaS business is growth.

The “growth effect” was highly statistically significant. In fact, a 10% (meaning 30% to 40%) increase in growth rate translated into a 3x (3x!!) increase in revenue multiple. That’s highly significant. And interestingly if you look at factors such as Gross Margin and EBITDA Margin they weren’t predictive at all. Nor was recurring revenue (meaning the % of revenue that was recurring vs. services). Below is another graph looking at the core correlation between growth and multiple (simply another way of showing the results I discuss above).

If I’d been on the ball a few months ago and posted these data back then, this would have been the end of the story. Markets value growth and growth above everything else (at least at the time). But, of course, the markets have changed since then and it’s important to note a few things because of this.

I have another post I’m working on describing why I don’t think we’re in a “bubble”. But even if that’s true, it doesn’t mean that the markets won’t go down, and more importantly for many of the people reading this, that the private markets won’t start shifting their focus from growth to other factors (i.e., profitability). We’re already seeing this in some markets such as security. And we’ve certainly seen in the past that when the markets shift their focus from growth to profitability they do so pretty quickly (briefly in 2011, before that in 2008 and dramatically in 2000/2001). Unlike some, I don’t actually have a view on how drastic a correction we’re headed into (as I said at the start of this paragraph, I don’t think we’re in a bubble to begin with, but we’re clearly experiencing turbulence, nonetheless; however the sky isn’t falling and I tend to agree with what my partner Brad Feld said in the article linked at the beginning of this sentence: “I think everyone will have an opinion and no one will have any real idea,”).

Much more on this in my bubble post upcoming, but I didn’t want anyone walking away from this note saying “Seth says grow at all costs!” I’m saying the markets are valuing growth to a degree that surprised me when I looked at the numbers, BUT that one should take that with a grain of salt given the current market conditions and the tendency for markets to quickly shift their focus. Smart growth is the right strategy (I said this months ago at our Summit as well). The best businesses are sustainable and grow at a pace and in a manner that sets their burn rate at an appropriate level relative to their funding and matching things like CAC to LTV in sustainable ways.

More soon…

Why Companies Fail

I’ve touched on aspects of this topic before, but thought it was worthy of a full post. Companies in the venture business fail all the time. As I wrote last year, the majority of venture rounds fail to return capital. With all the hype one reads in the startup press these days, that fact can be easily lost.

I’ve touched on aspects of this topic before, but thought it was worthy of a full post. Companies in the venture business fail all the time. As I wrote last year, the majority of venture rounds fail to return capital. With all the hype one reads in the startup press these days, that fact can be easily lost.

So we know that startups fail all the time, but why do they fail? Here are some common pitfalls based on our experiences (and here I’m referring not just to Foundry portfolio companies, although all of these lessons apply there as well, but also our observations of the broader markets).

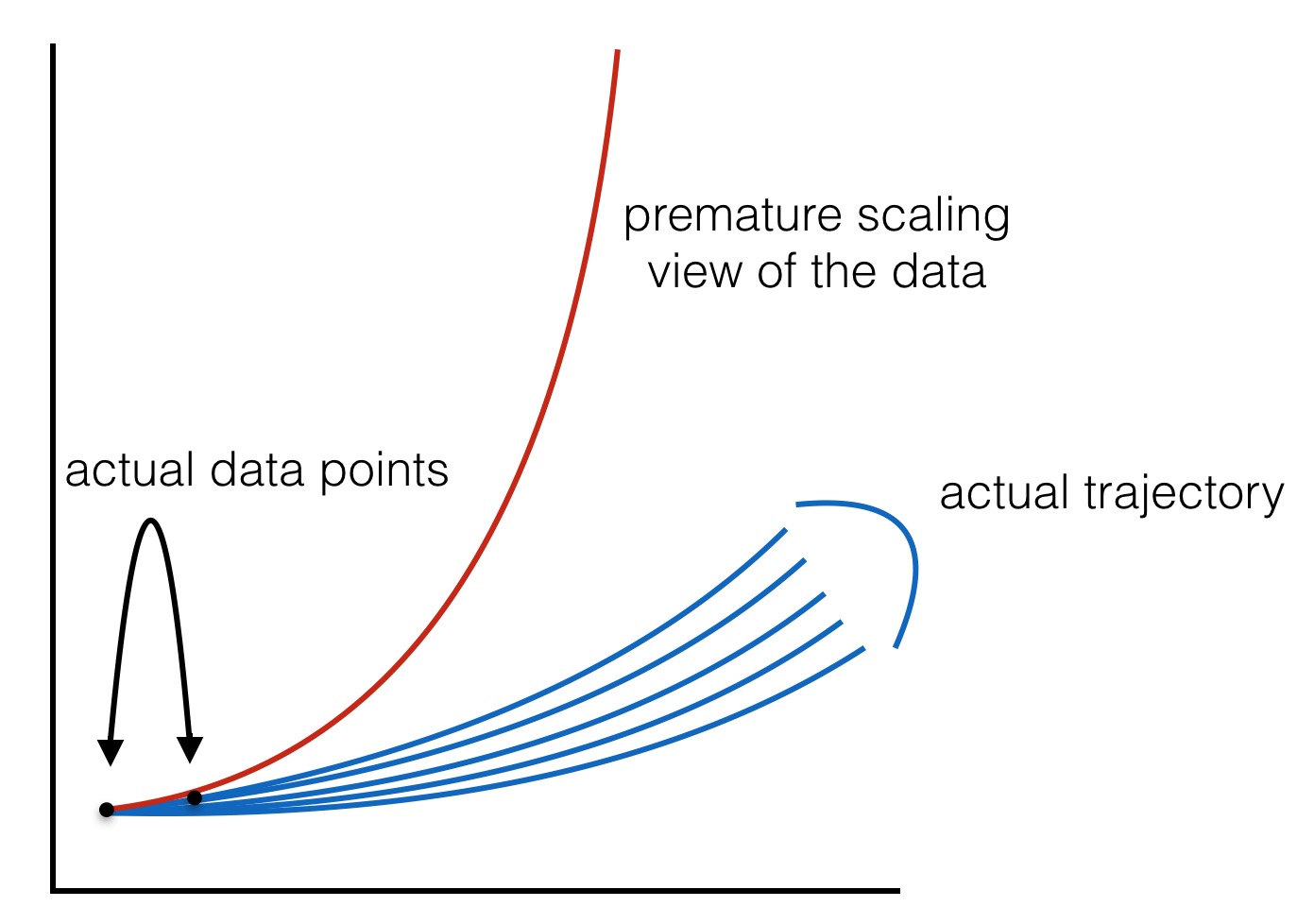

Premature scaling. The number one reason companies fail in my experience is premature scaling. Companies that fall prey to this typically 1) believe they’re in a winner take all market; 2) are impatient to get to “scale” (for all sorts of reasons); and 3) extrapolate early data incorrectly (or just ignore it). Every time this happens to me I vow it won’t again. And inevitably it does. The most dangerous pitfall above is #3 (#s 1 and 2 are exacerbating factors that multiply the effect). A company gets some early data on sales performance and either completely misinterprets it or believes that early sales scales linearly (or even worse, on a log basis). Then rather than increment up and test your sales performance hypothesis you hire like crazy (see #’s 1 and 2 again) and all of a sudden your burn rate is out of control. Reading it here in black and white this is something I’d never do. Ever. But that’s not how it works and unfortunately it happens with way too much frequency. Typically in retrospect these kinds of mistakes are obvious, but when you’re in the middle of it everything seems nice and logical. An adjunct to this is believing that whatever problem you’re having in your sales and marketing funnel will somehow be fixed by scale/time (classic example is deciding that fixing your CAC payback period is a matter of spending more on marketing, vs spending some time honing in on what specifically is failing and what is working).

Not recognizing that your sales problem is actually a product problem. This could be a blog post of its own, it’s so common and such an interesting topic. The typical response to lack of sales is to reexamine your sales and marketing organization. Perhaps you replace your VP of Sales ((hint: if you’re on your 3rd head of sales, you probably don’t have a sales problem) or perhaps you change marketing strategies over and over. Less frequently do companies look at their product and realize that their lack of sales isn’t at all related to their sales organization.

Not taking money when it’s available. Perhaps with the markets changing more entrepreneurs will learn that raising capital is actually hard, but in the last cycle we commonly saw companies over optimize for founder dilution and under fund their businesses – presumably with the assumption that more cash would be easy to raise if needed. Sometimes that worked. But often it didn’t (because often the circumstances that make you need more cash are the same ones that make raising that cash difficult). Countless times I’ve watched companies make the mistake of trading a small amount of dilution today for the hope of more money tomorrow. The risk of taking a bit more capital now is a little less ownership. The risk of running out of capital is your company shutting down. You do the math.

Lack of conviction. This is a dangerous one and often sneaks up on you – akin to watching a car crash in slow motion. As Gretzky once famously said, he skates to where the puck will be, not where it is now. To do that you have to have some idea of where the puck is headed. Some entrepreneurs get paralyzed by a fear of getting the market wrong that they sit back and wait for a sign of where they should go. This kind of passivity rarely works. I often tell CEOs that I’d rather us be wrong with convocation. Startups have limited resources and while getting feedback on what customers want or where a market is headed makes sense, at some point as a company you need to make a decision about where you’re headed and run hard there.

Time doesn’t heal everything. This is related to lack of conviction, but occasionally I see companies who feel that their job is to maximize the runway they have left. And while making sure you have time to execute against a vision is important, doing so by treading water never works. This is most prevalent in companies that are shifting their focus or vision from an initial idea to something new. As part of that process they cut burn and somehow get attached to the 34 months of cash runway they have left at their low point, struggling to hire back up for fear of seeing that number jump down. But no company succeeds by treading water and ultimately these companies die a slow, but predictable, death.

Careful introspection is important here. Typically it’s hard to admit when you’re in the thick of things that somehow you’re not a special case where the rules don’t apply (or put another way, it’s easy to squint at the data and suggest that you’re situation is different; it likely isn’t). And, of course, many times companies fail because they were just wrong about the market and the product they were trying to build. But understanding where companies typically fall short is a great way for you to lower your chances of falling prey to these common mistakes, and increase your chances of succeeding, even if your initial idea takes some iteration.

My final thought is an obvious one, but companies fail because they run out of cash and aren’t able to raise more (or sell the business). Many of the ideas above relate to spending cash either too quickly or on the wrong things (or not raising enough capital when you can). There’s a saying in the advertising business that 50% of ad spend is wasted, you just don’t know which 50%. The same can often be said of startups. In every startup that I’ve been involved in that’s failed, I can look back and see dozens of places where we wasted money (always thinking to myself: “if I could only have that money back to spend knowing what I know now.”). Ultimately your job as a CEO (and my job as an investor and board member) is to help you make smart investment decisions so that you waste as little money as possible on your way to building a successful business.

Once bitten but nothing learned …. betting on the Superbowl again

Apparently I didn’t learn from my experience last year. As you may recall, I bet Dan Levitan from Maveron $5,000 that the Broncos would beat the Seahawks in last year’s Superbowl (one of several ultimately losing bets). They failed to do so. In spectacular fashion. (truthfully I didn’t watch past the first play of the 2nd half) And that was just the most public bet I lost (that money went to Seattle Children’s Hospital, so at least I was supporting a good cause). There were others – less expensive but more humiliating. </sigh>

Fast forward a year and we’re doing it again. Dan gets to bet on his beloved Seahawks. And while the Broncos didn’t make it back for a rematch (and let’s be honest with ourselves – they weren’t going to beat the Seahawks even with their somewhat revamped defense this year), the Patriots did. Turns out I’m from Boston and that makes me a big Pats fan.

So…when the Pats win, Dan is going to donate $5,000 to Boston Children’s Hospital. On the off chance that I lose, Seattle Children’s gets another $5,000 from me. Like last year, I’d encourage some side bets – we actually raised several thousand more for Seattle Children’s by people taking on a similar challenge.

Go Pats!

Introducing Pledge 1% – Let’s make a difference together

There’s a great scene in Office Space where the movie’s heroes check their ATM balance after one of them has written a program to scrape tenths of pennies off of Paymetech (the movie’s fictional company) transactions. The guys figure this action will both go unnoticed and also generate a relatively modest sum for them. Instead when they check their balance it turns out that the sum of their tiny rounding transactions actually equated to over $400k to them over a weekend!

There’s a great scene in Office Space where the movie’s heroes check their ATM balance after one of them has written a program to scrape tenths of pennies off of Paymetech (the movie’s fictional company) transactions. The guys figure this action will both go unnoticed and also generate a relatively modest sum for them. Instead when they check their balance it turns out that the sum of their tiny rounding transactions actually equated to over $400k to them over a weekend!

It’s a funny scene (and a funny movie) but the moral here is actually important: The sum of a large number of small actions can be huge.

Today we’re announcing the launch of Pledge 1%. A joint effort between The Entrepreneurs Foundation of Colorado, The Salesforce Foundation and The Atlassian Foundation, Pledge 1% encourages entrepreneurs and companies to give back to their local communities through a gift of equity, profits and/or product. With Pledge 1% we’re aiming to aggregate a large number of smaller transactions to create meaningful impact.

For years we’ve seen the benefit of companies giving back to their communities through the Entrepreneurs’ Foundation network. Since it’s founding 7 years ago, EF Colorado alone has generated over $3M in direct philanthropy back to local non-profits. And we’ve seen participating companies benefit from the incorporation of clear values from their very founding.

But we can and should do so much more.

Pledge 1% aims to encourage all companies to incorporate a small pledge of philanthropy into their corporate culture through the pledge or gift to a non-profit of their choosing. This gift can be in the form of stock from the company, a pledge of stock from founders or other employees, gifts of time, gifts of profit or gifts of product. We’re encouraging the entrepreneurial community to put a stake in the ground around the importance of giving back. Pledge 1% acts as a clearing house for these gifts and pledges with simple tools to encourage and facilitate giving. In addition to myself, the Pledge 1% founders include Mark Benioff of Salesforce, Ryan Maretns of Rally, Scott Farquhar of Atlassian, Jeremy Stoppleman of Yelp and Dan Siroker of Optimizely.

Check out what we’re doing at www.pledge1percent.org. And join me in making the pledge.

IPO or M&A? Here’s exactly how large companies exit

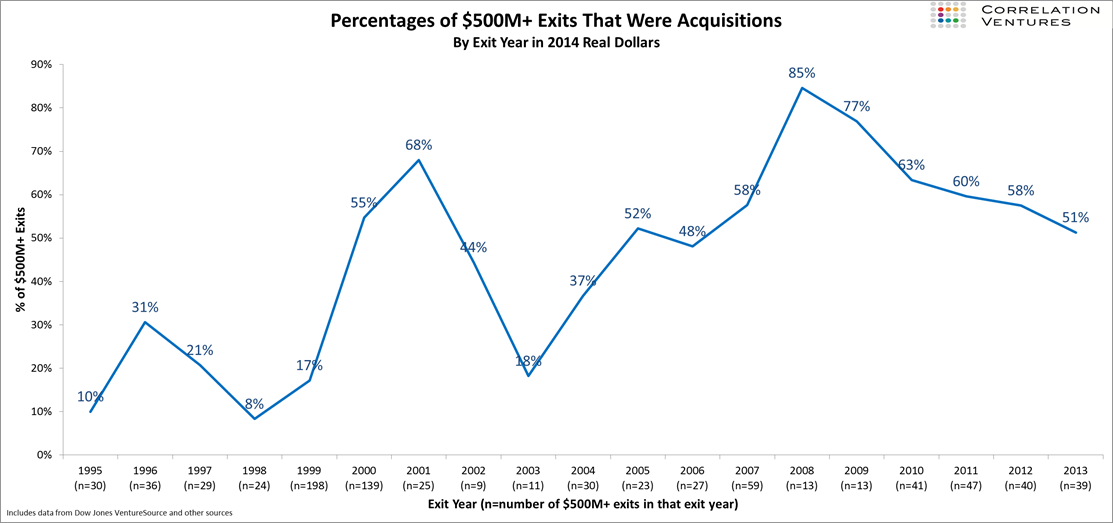

I wrote a post a few months ago based on some data from Correlation Ventures about the distribution of returns on venture deals (which revealed that outsized winners are, in fact, much more rare than most people think).

Today I’m focusing on companies in those top return categories with some new data from Correlation that show the percentage of large exits (>$500M) that are generated through M&A vs. IPO (quick side note: I seriously love how much information Correlation collects and how free they are in letting me post about it – as a reminder, Correlation is a firm that co-invests based on an algorithm that predicts the success of the a company; we’re in a few deals together and I can tell you the process is quick and painless; end of advertisement, but seriously – these data are from their work and the fact that they’re so interesting shows why the model works for them).

The graph below shows the trend of exits – IPO vs. M&A over the past handful of years (side note here that Foundry, like many firms, considers an IPO a financing event, not an exit in and of itself; although obviously it can be a path to an exit shortly thereafter).

A few key take-aways here:

– Acquisitions represent about half of all large exits in recent years, showing that both are – at the moment – reasonable paths to exit.

– There’s quite a bit of variability year to year (and cyclicality – not surprisingly), but the overall trend has been to more larger acquisitions (at least relative to IPOs). This reached it peak in 2008, although that may in large part be due to the lack of a public market option at that time.

– Generally speaking this trend holds true regardless of the absolute number of large exits in a given year (this is from the underlying data – not the graph, obviously).

I find data like these fascinating. Humans are horrible at proper attribution (a subject for another post) and I think this is particularly true in a hype driven industry such as venture/entrepreneurship. We all latch on to the big stories and the outlier returns – likely why so many people wrote me after my post on the distribution of venture exits and why there was so much interest on Twitter about it – the data didn’t match the heuristic people had in their heads. For me at least the same is true here – I would have expected the percentage of large exits from M&A to be significantly higher than exits through IPOs.

And that, of course, is why it’s important to actually look at the numbers rather than guess.