Venture Capital Deal Algebra

I’m intending this blog to be a mixture of my personal thoughts on being a venture capitalist (and my travels through the maze of the VC world); thoughts on life more generally; and what I’ll call VC 101 tips and pointers. One of the things I’ve noticed (and this is something that I’m happy to say the TypePad statistics really do a nice job of, my rant about them last week aside . . .) is that my VC 101 posts get a lot of traffic (and cross-posting/track-backs that drive this traffic). The impetus for my starting this blog was to capture my personal thoughts on being a VC, however I want to be sure I mix up my content to attract a broader array of readers. So, I’m going to keep up with the VC 101 posts, since it seems like there’s a segment of people who read my blog that sincerely appreciate an insiders view on the mechanics of venture capital. Today’s post is on deal algebra. Basically it’s a run-down of deal valuation terms. When you live in the VC world and use these concepts regularly, you sometimes forget that they are not necessarily obvious in their meaning (which can lead to confusion down the road; not good when you are embarking on a new venture with an entrepreneur). We noticed this a few years back, and as part of a larger effort to gather information that would be helpful to our portfolio companies Dave Jilk created this summary of key VC deal terminology that we sent around to a bunch of our CEOs and other people we work with (note: I’ve made some edits to Dave’s original work mostly for length). VC Deal Terms: In a venture capital investment, the terminology and mathematics can seem confusing at first, particularly given that investors are able to calculate the relevant numbers in their heads. The concepts are actually not complicated, and with a few simple algebraic tips you will be able to do the math in your head as well. The essence of a venture capital transaction is that the investor puts cash in a company in return for newly-issued shares in the company. The state of affairs immediately prior to theinvestment is referred to as “pre-money,” and immediately after the transaction “post-money.” The value of the whole company before the transaction, called the “pre-money valuation” (and is similar to a market capitalization). This is just the share price times the number of shares outstanding before the transaction: Pre-money Valuation = Share Price * Pre-money Shares The total amount invested is just the share price times the number of shares purchased: Investment = Share Price * Shares Issued Unlike when you buy publicly traded shares, however, the shares purchased in a venture capital investment are new shares, leading to a change in the number of shares outstanding: Post-money Shares = Pre-money Shares + Shares Issued And because the only immediate effect of the transaction on the value of the company is to increase the amount of cash it has, the valuation after the transaction is just increased by the amount of that cash: Post-money Valuation = Pre-money Valuation + Investment The portion of the company owned by the investors after the deal will just be the number of shares they purchased divided by the total shares outstanding: Fraction Owned = Shares Issued /Post-money Shares Using some simple algebra (substitute from the earlier equations), we find out that there is another way to view this:Fraction Owned = Investment / Post-money Valuation= Investment / (Pre-money Valuation + Investment) So when an investor proposes an investment of $2 million at $3 million “pre” (short for pre-money valuation), this means that the investors will own 40% of the company after the transaction:

$2m / ($3m + $2m) = 2/5 = 40%

And if you have 1.5 million shares outstanding prior to the investment, you can calculate the price per share: Share Price = Pre-money Valuation / Pre-money Shares = $3m / 1.5m = $2.00 As well as the number of shares issued: Shares Issued = Investment /Share Price = $2m / $2.00 = 1m calculate with post-money numbers; you switch back and forth by adding orThe key trick to remember is that share price is easier to calculate with pre-money numbers, and fraction of ownership is easier to subtracting the amount of the investment. It is also important to note that the share price is the same before and after the deal, which can also be shown with some simple algebraic manipulations.

A few other points to note:

- Investors will almost always require that the company set aside additional shares for a stock option plan for employees. Investors will assume and require that these shares are set aside prior to the investment.

- If there are multiple investors, they must be treated as one in the calculations above. To determine an individual ownership fraction, divide the individual investment by the post-money valuation for the entire deal. For a subsequent financing, to keep the share price flat the pre-money valuation of the new investment must be the same as the post-money valuation of the prior investment.

You Need More Nietzsche in Your Life

Nietzsche has so many famous quotes it’s sometimes hard to choose just one (most have heard that which doesn’t kill you makes you stronger although I suppose few realize that it was the German philosopher who first penned it). My favorite, perhaps, is: there are no beautiful surfaces without a terrible depth. I like it in particular because in many ways it describes Nietzsche himself. His writing is often beautiful, but with a depth that sometimes takes time to fully recognize.

In their new book, The Entrepreneur’s Weekly Nietzsche: A Book for Disruptors, Brad Feld and David Jilk pick out some of their favorite Nietzsche quotes and form chapters around business lessons from them. It’s a brilliant construction and one that adds context and meaning to Nietzsche and his writing. You’ll recognize many of the contributors to the book – Reid Hoffman wrote the introduction (I didn’t realize that Reid studied philosophy before turning to technology as a career), and many entrepreneurs contributed chapters (I wrote one as well, in fact).

There are many lessons to be learned from the last year – of the importance of connections to those around us; of how fragile our economy is – especially in certain sectors; about what’s really important. One of the most important to me was the power of slowing down. I’ve always known this – and strove to create space in my life to do it (often failing). But Covid forced it in ways that were unexpected. Especially from this perspective, the timing of The Entrepreneur’s Weekly Nietzsche is perfect. I’ve had a pre-release copy for a few weeks now and it’s how I start my day: quietly contemplating a Nietzsche quote and considering its meaning for my personal and work life. Thank you to Brad and David for this gift.

I hope you’ll consider buying the book and trying a similar routine. Nietzsche isn’t a philosopher to be devoured. Rather, his writing is meant to be contemplated and considered. The Entrepreneur’s Weekly Nietzsche is a wonderful, guided way to do just that.

You can purchase the book on Amazon and other sites. The book’s website with more information can be found here.

Apply early, apply often

TechStars applications for this summer are officially open and I’d encourage any budding entrepreneur with a half-baked (or quarter baked – or fully baked) idea they are passionate about to apply.

For those of you who are not familiar with TechStars, it’s a program started by successful Boulder entrepreneur David Cohen that brings about a dozen promising start-up teams to Boulder for an intensive summer of work on their start-up business idea. You can read more about what the teams last year worked on (and some of the machinations they went through to get there) on both David’s blog and the TechStars web site.

I was a huge fan of TechStars last year and worked closely with a handful of the teams (most notably Filtrbox, for whom I was the "lead mentor"). For entrepreneurs looking to get their feet off the ground, there’s no better experience and no better way to quickly get access to everything the Boulder entrepreneurial ecosystem has to offer. For a more detailed perspective from one of last year’s participants, check out what Tom Chikoree has to say about the experience in his blog on the topic.

If you’re interested there’s more information about the program specifics and detail on how to apply on the TechStars web site (details and application info).

Without question TechStars is a huge commitment, but one that brings its participants a lasting experience that they will continue to benefit from for many years. Apply!

Check the job boards

Finding information out about your competitors is something that all companies do on a regular basis. Trolling web sites, reading blogs, setting up news alerts for articles, talking to customers and prospects, trolling trade show booths and listening in on webinars are all pretty common occurrences in the business of knowing what you don’t know about your competitors.

One great way to get a pulse on what’s going on down the street is to keep your eye on your competitors job board. The pace of hiring and the positions with open recs all give incredible (and generally overlooked) insight into the state of their business.

Board Observer vs. Board Member

Venture capitalists generally participate in boards in one of two fashions – either as actual board members or as board observers (see Brad and Jason’s post on Term Sheets – Board of Directors — for more information on how we take positions on boards). As an associate at Mobius I was not able to take actual board seats, so I took the board observer position in the companies I worked with (note that generally this isn’t an official designation – although I have seen board agreements that require the venture firms to specifically designate the board observer; more commonly its just a seat at the board table reserved for someone from the venture firm other than the board member). As an observer I am an active participant in board meetings, but I don’t vote on any board matters and in some cases need to step out of meetings (typically to protect attorney/client privilege, which covers board members but not board observers). The boards I am involved with have all welcomed me into all of the regular and executive sessions of their meetings. Different firms treat the distinction between board observers and board members differently. At Mobius I am encouraged to be an active participant in the businesses I work with and I have never been shy about voicing my opinions at meetings. Other firms have a similar philosophy, but some feel that observers are just that – people who can attend meetings but should not participate. I’m planning a series of posts with some of the CEOs that I work with, so you can get a sense of how the relationship dynamic plays out. Stay tuned for that.

One of the big changes from my recent promotion to principal is that I’m now able to take actual board seats. I’m going to take this leap very soon and am interested to see what the differences really are sitting on the other side of the table. I won’t attend my first meeting as a board member until February, so we’ll all have to wait until then for the answer, but I plan to write about it here as it strikes me as a very important step (and milestone) in my progress as a venture capitalist. More on the company that I’m stepping up my involvement with in a future post as well, but I wanted to clarify thedistinction in roles before I get to that.

VC’s are conspiring to take over your business

John pointed me to a Peter Ireland blog post and asks whether VCs really do co-opt businesses on a regular basis – investing with a plan to replace founders and bring in their own management. "[S]ounds kinda scary," he writes, "the thought that a ‘clever’ VC could take away one’s company just like that…"

Scary indeed. And while founding CEO’s are certainly replaced in venture backed businesses, it’s significantly overstated to say that "in about 50% of instances where an early stage company actually succeeds in raising venture capital, the founder CEO is fired within the first year".

Before I get into this, however, I feel compelled to remind you that you really should not be taking venture capital in the first place (remember?) and that investors in your business get both positive control (the ability to vote as shareholders and board members for various actions) and negative control (the long list of things that you can’t do without your investor’s approval) – see Brad and Jason’s term sheet series for more detailed information on this.

So . . . now that you’re not taking venture capital, or if you are you fully understand what control your new funding partners have over your business you can hopefully minimize the chances that your big bad VC’s term sheet is just a back-door way to gain control of your business. Most VCs are actually pretty up front about this as they are making their investments. After all, a significant part of what we’re investing in is the people who actually came up with the idea in the first place (meaning you and your co-founders). That said, recognize that differences of opinion really do happen in companies, and that you may not always see eye-to-eye with your investors (or they with your management team or co-founders for that matter) about the right path forward. Founders are sometimes asked to leave their companies or to take on a diminished role. Founders themselves sometimes have disagreements that lead to one or more co-founders leaving a company.

Here’s a couple of things I’d suggest that you think about to avoid the situation that John is asking about:

- Know your investors. All money may be green, but what comes along with that money is most certainly not created equally. Make sure you do due diligence on your investors and board members. Ask other entrepreneurs who have worked with them about their experiences. Talk to friends in the industry to get a sense for their overall reputation. Ask your prospective VCs how they imagine working with you and the company. You’re about to enter into a multi-year relationship with these people – make sure you’re comfortable.

- Understand the agreements you’re signing and have good representation. Investment documents are complicated and pretty specialized (and not something you’ve probably dealt with on a regular basis). Make sure you have a good lawyer and that they fully explain to you what you’re signing. Know what rights you have and what rights your investors have.

- Negotiate up front. Things like your vesting schedule, vesting acceleration if you are fired, voting agreements and board representation are all negotiated as part of your financing deal. While you can’t solve for every possible situation, the good lawyer you hired (see #2) should be able to help you figure out with your investors how these and other key items will work.

- Fill your board. If you have a spot designated for an independent board member, find one. If you and your co-founder each get a seat – make sure you’re active participants in the business of the board.

- Stay close to your investors and board – keep things in the open. Take responsibility for your relationship with your investors and your board. Reach out to them on a regular basis for advice and help. Make sure they are up to speed on important decisions and be open about the challenges you are having running your business and determining strategic direction.

At the end of the day, it comes down to a combination of trust and communication. The best way to avoid surprises is to know your investors and board before you formalize your relationship with them and to stay close to them once you do.

Some more data on Venture outcomes

Quick update here. The data I site below is from Foundry LP StepStone. Since my original post I’ve confirmed with them that they’re ok with my identifying them as the source of the data. And they’ve offered to help me play with the raw data of a future report – I’ll work on some interesting updates here soon!

Yesterday’s post on venture outcomes – Venture Outcomes are Even More Skewed Than You Think – generated lot of traffic. Clearly, it’s interesting to put real data against a heuristic and see how reality maps to our expectations. As I pointed out in my post, the data set from Correlation Ventures I was working with had some limitations. For starters, I didn’t have the raw data to run my own cuts of the analysis. And more importantly the data were financing level, not company level. A bunch of people asked me about this and I’m working with Correlation to see if the next time they do this analysis we can get a few different views of the data.

In the meantime I went poking around for some additional information and remembered an analysis that one of our investors sent me on roughly the same subject. I thought given the interest in my last post I’d put it up for further discussion. Still not exactly how I’d parse this if I had access to the full data set, but interesting nonetheless. This analysis is on a company basis, not a financing basis (the chart is labeled “Deal” but in this case that means company, not round). I should also note that its skewed a bit towards better performing funds. This was an internal analysis by an LP so I’m not able to release the full report but the data set represented over 3,000 companies and more than $20Bn in invested capital and spanning years 1971 through 2012. The data only represent companies that have exited (and not, for the more recent fund vintages, companies current carrying value). It’s also worth noting that this data set likely shows a slight upward bias, reflecting this LPs selection over the years of better performing funds vs the VC average (from the internal report: “In our view, the data set is skewed toward higher quality funds; the average returns of these deals across vintage years outperform the VC average.”).

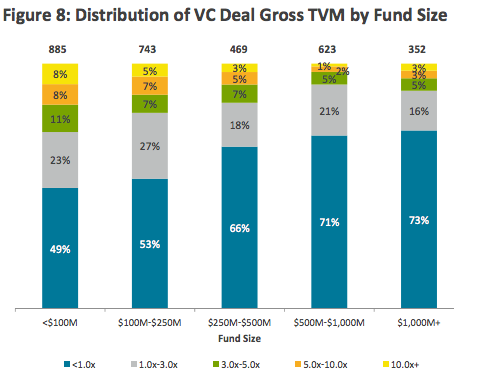

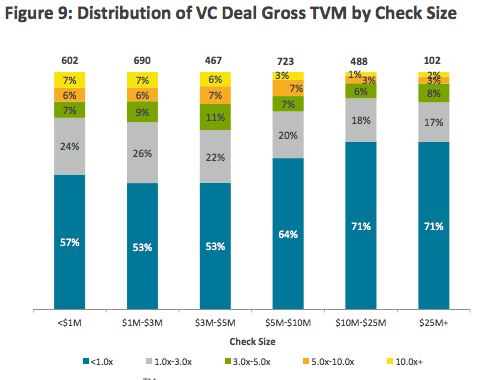

The first chart below shows the distribution of venture outcomes by fund size. Interestingly, the loss ratio of smaller funds (where outcomes are <1x) is smaller as a percentage of the portfolio than for larger funds. 49% of deals for funds smaller than $100M fail to return capital, while 73% of deals from larger funds failed to do so. The top end showed the same trend between small and large funds – smaller funds were significantly more likely to produce exits of 5x or greater vs large funds. These data largely track to investment size with larger checks producing not only fewer outsized winners (as you might expect given the nature of larger rounds) but also producing far more companies that failed to return capital (which you might not expect given the nature of the types of deals that raise larger amounts – stage, risk profile and investment structure).

One obvious conclusion from these data (and something I’ve seen supported by other data sets as well, although I haven’t written about directly before) is that smaller funds outperform larger funds. There’s more to that argument than is contained in the charts above (with well in excess of 50% of all deals failing to return capital, there’s plenty of devil in the details to make that conclusion) however the report I pulled these from – the writers of that report had the full data, of course – clearly articulated that as one of their conclusions. More on that in a separate post at some point. These numbers generally support the conclusions I drew yesterday about the challenge of finding unicorn investments. But the data also suggest that while they don’t truly follow the 1/3, 1/3, 1/3 heuristic, smaller funds come closer to that hypothetical portfolio distribution than do larger funds (at least above average funds do). In this data set, funds smaller than $250M invest in companies generating greater than 3x return 23% of the time and fail to return capital on a little over 50% of their investments. This compares to less than 10% of investments by funds greater than $500M generating a 3x return and almost 72% failing to return capital.

All of the data aside, it’s clear that venture returns are generated by a minority of funds that find themselves in the outlier deals (and that being a successful venture capitalist is quite difficult).

The power paradox

Dacher Keltner (Psychology prof at Cal) has written a fascinating article that describes some of the important attributes of leaders. He discusses these attributes in the context of obtaining and maintaining "power" – really leadership if you’re reading the article from the eyes of a VC or entrepreneur. The title of his article refers to the fact that the attributes necessary to obtain positions of power and leadership are the very attributes that tend to be eroded by those positions themselves (i.e., once people obtain power, they tend to lose it by acting in a way that is antithetical to the reason they rose to that position in the first place).

Reading the piece through the eyes of a VC, there are a couple of great lessons for those in leadership positions and Keltner really nails a few very common traps that CEOs – particularly first time CEOs – fall into as they navigate the complicated management dynamic with their management and board. As the former manager of a large organization (before becoming a VC I managed a 250 person organization) I see some of the rookie mistakes that I made as I navigated my first really meaningful management position (which is to say managing more than a dozen or so people). A couple of points stand out (but be sure to read the whole article):

[O]ne’s ability to get or maintain power, even in small group situations, depends on one’s ability to understand and advance the goals of other group members. When it comes to power, social intelligence—reconciling conflicts, negotiating, smoothing over group tensions—prevails over social Darwinism.

One of the key jobs of a CEO is to manage and guide organizational conflict and disagreement – on product direction, on time-lines, on strategic direction, etc. While a firm hand is often required – the hammer is generally not. Being a dictator – and putting your opinions and feelings above those of any and everyone else is a quick way to erode one’s standing as leader and diminish the respect for you from your management and board.

Time and time again, empirical studies find that leaders who treat their subordinates with respect, share power, and generate a sense of camaraderie and trust are considered more just and fair.

Successful leaders not only recognize their own limitations and hire people around them to fill in the gaps, they tend to be consensus builders and somewhat hands-off delegateors. They "share power" and show respect to their teams by empowering decision making and individual action, rather than micro-managing and second-guessing every decision. Thoughtful managers define general course and direction and for the most part allow their teams to run their respective areas. If you’ve hired well, this should be the natural dynamic amongst a management team (and with each other, not just with respect to their interaction with their superiors).

[P]ower is [not] acquired strategically in deceptive gamesmanship and by pitting others against one another.

This is particularly true at the board level, but also clearly relevant amongst any group of company managers. Selectively managing information flow to support a specific, pre-determined outcome; engaging in a series of one-off conversations with the intent of lobbying your position or picking off the group one at a time eventually back-fires. Acknowledging group differences, understanding the various perspectives brought to the table by your management team and making your case out in the open are much more effective ways to drive a process of decision making.

I look forward to other thoughts on the subject – please comment away!

The bird is cold

Yahoo launched a private version of what they are calling FireEagle – a service that allows you to track your location to be shared with applications that build to the FireEagle API – its basically a location “broker” (for self reported location). I’m a big fan of location based services (we’re investors of IP geo-information company Quova and geo-spatial platform company deCarta), so the idea of a common platform upon which to build location aware applications. Through Quova, we’re small investors in Navizon who has a similar dev platform to FireEagle.

So you can imagine my disappointment when I clicked over to the “application gallery” tab only to find nothing there. Nothing. Not a single “this is cool stuff, we’ve thrown a few things up to get you going” application. Where is the Facebook “I’m here; my friends are there” integration? Or better yet, the Twitter “friend location tracker”? Or even a simple widget for my blog that reports my current location Nadda. Just a note that says essentially “there’s no there there yet”. I don’t get the point of launching a service – even just to the developer community, which is clearly their intent from the email I received – without at least a few demo apps. I have to imagine that there are scores of companies out there with the time, talent and inclination to have done the work to be included with this launch. Hopefully Yahoo/FireEagle will quickly get its act together and have a full application library before they take this service much further.

I have a few more invite codes if you’re looking to check it out. Send me a note directly and if they are not all taken, I’ll hook you up.

I’m excited about what Yahoo is doing – just want to see more meat on the bones of the bird. . .

Update: My invite codes have all been given out.

A day in the life of a VC

One of the most common questions I get asked from people outside the VC industry is “what’s a typical day like?” It’s a good question, but a hard one to answer – my days are extremely varied (this is one of the things I really like about my job, in fact). The type of work I do on any given day is very dependant on what’s going on with the companies that I work with (financing, m&a, planning, putting in place a bank line, rolling out new products, etc.), and every day (or hour) seems to bring something different. I’ve tried a few approaches to answering this question – typically some variant of “on average I spend x% of my time on sourcing new deals; y% on financings; z% working with portfolio companies on operations; etc.). The problem with this is that, while it may provide some insight into how I spend my time in a typical month (or quarter), it doesn’t really answer the question, nor give much of a real flavor of what Ido day to day. Since one of my goals with this blog is to write about the experience of being a VC I thought I’d try to do a better job of answering this question by writing about a couple of different days that I think typify the VC experience. The idea here is not to generalize, but rather to report on a couple of days that feel are ‘typical’. I had one recently (that inspired me to try to tackle this question) – it went something like this: Early Morning: Spent the morning working up a term sheet for an investment that had recently been approved by the firm. It actually wasn’t my deal, but the principal who had sponsored it was on a business trip and I was helping out by pulling the term sheet together. To do this I had to work up a version of the company’s cap table that I could play around with (I had one from the company, but the structure of it didn’t allow me to manipulate it in the way that I wanted to). I also spent quite a bit of time with the financing docs from their last round – Series A term sheets are much easier to write than term sheets for follow-on financings where I need to account for the existing cap structure as well as understand what terms I want to keep the same vs. change from previous rounds. The whole process took several hours, after which I sent it off to the partner involved in the deal and our general counsel to take a quick look before sending it to the company.

Late Morning: We were closing on an investment today as well. I had already reviewed the deal docs, but took a last look through the schedules this morning and double checked the numbers again. After a couple of points of clarification with the lawyers, all looked good, so we sent a note to our operations group to initiate the wire transfers.

I also spent about 45 minutes on the phone with the VP of BD of a public technology business that is in a space in which we’ve made several investments. I was interested in his impressions of trends in the industry and specifically his company’s key initiatives for 2005. The company is also a potential partner/acquirer of a few of our investments and I wanted to be sure he was aware of some of the companies in the portfolio.

Lunch: I had lunch with two entrepreneurs who were the founders of a business we invested in several years ago. Their company was sold relatively quickly and all involved (investors and founders) were pretty pleased with the outcome. After working for the acquirer for a while they were ready to get back to something more entrepreneurial and had been floating around some ideas together. They’d settled on something they wanted to pursue and wanted to bring me up to speed on their thoughts/get some feedback. We’re supporting them in their early efforts both by being a sounding board for ideas as well as by giving them some space in our office to use while they get started.

Afternoon: My afternoon was pretty open of meetings, so I returned a couple of phone calls (the most interesting of which was talking to one of the CEO’s I work with about his funding strategy – we’re looking to put a debt line in place at his business and needed to pull together some information before deciding exactly how much we wanted and how we were going to approach lenders). I also talked with an old friend of mine who works for a VC in Boston. We catch up periodically to get a pulse on what each of us is looking at, as well as to keep up personally (he and I worked together at Morgan Stanley back in the mid-90’s). I also had some time to sort through the day’s e-mail – something I hadn’t been able to do in the morning (I get about 200 e-mails a day, so keeping on top of incoming messages is important for staying current).

So there you have it. Not particularly glamorous, but pretty typical of what I spend my time doing. Term sheets, cap tables, financing docs, lots of time on the phone – all in all a relatively usual work day.

For another perspective on a typical VC day, see David Hornik’s post on the subject here. His extremely funny follow up post to that is here (a copy of parody of VC life that became very well traveled in the VC and legal circles).