An Update on The Colorado Talent Network

Social Distancing or Social Distrust

I was at the grocery store the other day and thankfully most people were wearing masks (a big change from a few months ago when I was literally laughed at when I wore a mask to that same story, early on in the crisis). However, walking around, people’s body language really struck me. In our efforts to socially distance, we are going out of our way to stay away from each other. That’s exactly what we should be doing, but I felt like there was almost a veneer of distrust and mistrust between people. What people are thinking is made harder to understand because everyone’s facial expressions are hidden behind their masks. Is that person smiling at me or growling as I gave them space coming off the end of an isle? Did they hear my muffled voice say something kind as we passed or did I come off as mad?

I was at the grocery store the other day and thankfully most people were wearing masks (a big change from a few months ago when I was literally laughed at when I wore a mask to that same story, early on in the crisis). However, walking around, people’s body language really struck me. In our efforts to socially distance, we are going out of our way to stay away from each other. That’s exactly what we should be doing, but I felt like there was almost a veneer of distrust and mistrust between people. What people are thinking is made harder to understand because everyone’s facial expressions are hidden behind their masks. Is that person smiling at me or growling as I gave them space coming off the end of an isle? Did they hear my muffled voice say something kind as we passed or did I come off as mad?

It’s a good idea to consider that as we’re distancing from everyone in our lives except for members of our own household, it’s important to maintain the social ties and graces that keep us bonded together as a society. I’m not talking about zoom happy hours with your friends. I’m talking about how we treat strangers when we do find ourselves out and about.

The other day, my wife was at a different grocery store, talking to someone in the long line to check out (long in part because people were appropriately distancing). She described people eyeing her suspiciously, just for talking – as if we’re not supposed to be interacting in any way.

Let’s not lose our humanity in this. There are so many examples of people being generous with their time, energy, or money during this time of crisis, which is fantastic. But it’s also important in our day to day interactions that we do not lose a sense of our communities and connectedness to each other, even if we cannot be in close physical proximity.

Circular Advice from the SBA

Quick preface to this note. I’m not your lawyer and I’m not giving legal advice.

Quick preface to this note. I’m not your lawyer and I’m not giving legal advice.

As I wrote about at the beginning of the week, the SBA has made a mess of the Payroll Protection Program. Yes, there are some challenges to parts of the structure of the program, but I was referring in that post to the SBAs implementation of the program and the varied guidance they’ve given since the program’s launch. They have been inconsistent, unclear and sometimes contradictory to statements made by Treasury and administration officials. It’s led to confusion on the part of companies who applied (or were thinking of applying) and ultimately to greater loss of jobs as companies struggled to understand whether they qualified or not. I can tell you from the board rooms that I’ve been in (virtually, of course) that people are genuinely trying to understand the intent and do the right thing, even if turning down the money meant that they needed to lay off or furlough some workers to keep costs in check.

Last week the SBA said it would offer further guidance before May 14th and many companies postponed or agreed to revisit decisions about the loan program once that guidance came out. The assumption had been that the SBA would offer further clarification about the “economic necessity” threshold that was prescribed in the original program language as well as a further update to its FAQ question #31, which stated that companies needed to consider “their ability to access other sources of liquidity sufficient to support their ongoing operations in a manner that is not significantly detrimental to the business.” (I wrote about this at length in my post on the PPP’s challenges earlier this week).

Yesterday – May 13th, one day before the SBA’s “safe harbor” deadline (the date that they had previously said that companies needed to return the money if they felt subsequent guidance disqualified them and be essentially absolved of any wrongdoing) – the SBA released their new “guidance” and updated their FAQs related to the program (the SBA maintains a single document for this – when they update it, they simply tack on the new guidance to the end).

The wait was not worth it.

I assumed that the SBA would offer thoughts on “economic necessity” such as how many months of runway a company might have, above which they would generally be deemed not to have necessity. Or perhaps would suggest a threshold for how much revenue, bookings or other key metrics of a business might need to be down in order to qualify. Or even just a general view about how companies should consider the overall future economic impact of Covid (can we even look to the future in making our determination of need, for example). Certainly they would address the question about “other sources of liquidity”.

But they did not. They waited until the day before their deadline and ultimately added little in the way of guidance. In fact they appear mostly to have repeated what had already been said and on a few key points backtracked completely. The key FAQ related to the economic necessity question read as follows. I added the emphasis.

46. Question: How will SBA review borrowers’ required good-faith certification concerning the necessity of their loan request?

Answer: When submitting a PPP application, all borrowers must certify in good faith that “[c]urrent economic uncertainty makes this loan request necessary to support the ongoing operations of the Applicant.” SBA, in consultation with the Department of the Treasury, has determined that the following safe harbor will apply to SBA’s review of PPP loans with respect to this issue: Any borrower that, together with its affiliates, received PPP loans with an original principal amount of less than $2 million will be deemed to have made the required certification concerning the necessity of the loan request in good faith.

SBA has determined that this safe harbor is appropriate because borrowers with loans below this threshold are generally less likely to have had access to adequate sources of liquidity in the current economic environment than borrowers that obtained larger loans. This safe harbor will also promote economic certainty as PPP borrowers with more limited resources endeavor to retain and rehire employees. In addition, given the large volume of PPP loans, this approach will enable SBA to conserve its finite audit resources and focus its reviews on larger loans, where the compliance effort may yield higher returns.

Importantly, borrowers with loans greater than $2 million that do not satisfy this safe harbor may still have an adequate basis for making the required good-faith certification, based on their individual circumstances in light of the language of the certification and SBA guidance. SBA has previously stated that all PPP loans in excess of $2 million, and other PPP loans as appropriate, will be subject to review by SBA for compliance with program requirements set forth in the PPP Interim Final Rules and in the Borrower Application Form. If SBA determines in the course of its review that a borrower lacked an adequate basis for the required certification concerning the necessity of the loan request, SBA will seek repayment of the outstanding PPP loan balance and will inform the lender that the borrower is not eligible for loan forgiveness. If the borrower repays the loan after receiving notification from SBA, SBA will not pursue administrative enforcement or referrals to other agencies based on its determination with respect to the certification concerning necessity of the loan request. SBA’s determination concerning the certification regarding the necessity of the loan request will not affect SBA’s loan guarantee.

This is a lot of words to basically about-face on much of the bluster coming from Treasury while offering no real guidance on the key questions I described above. Basically the SBA is saying that loans of less than $2M will be deemed to be requested in good faith and won’t be reviewed. Except in the 3rd paragraph they say that some smaller loans will actually be reviewed (“other loans as appropriate”). Although the document is inconsistent, it does seem appropriate to at least hold out the threat that some smaller loans will be reviewed (certainly some will have not been made in good faith or even been fraudulent; in fact likely at a higher rate than larger loans).

The real action is in the last paragraph. Here the SBA surprised pretty much everyone by basically saying “we’ll review your loan and if we think you didn’t qualify the penalty will be making you pay it back.” This essentially extends the safe-harbor they already offered (which required companies to pay back a loan in order to qualify). There’s some grey area there, because in theory some other agency could take up enforcement action against a company that didn’t return the money prior to May 14th, but this seems like an unlikely scenario. To be clear, companies that take the money and they are required later to pay it back (but who in the meantime kept people employed and spent the money in ways they wouldn’t have if they had never taken it in the first place) are on the hook for the cash, so there are real consequences to getting it wrong. But for many companies on the bubble the consensus seems to be that they should take the money, apply for forgiveness (which will trigger a review of the loan, per the new guidance) and let the SBA decide if they qualified or not. It’s hard to argue with that logic given this new guidance. Especially because it appears the money in the program is not going to run out quickly (and therefore the argument that one company is effectively taking money from another company that didn’t get their loan application in as quickly is gone).

Personally, I was hoping for more. We’ve tried to be thoughtful in our approach to the PPP program and the SBA’s guidance. But with this latest round of advice, it’s hard to argue that companies on the margin shouldn’t lean on the SBA to arbitrate whether they qualified or not and stop their board level arguing. I know of a number of companies that had decided to return the loan but reversed course because of this new guidance, or who were on the fence waiting for the new guidance and have now agreed to keep the money and let the SBA weigh in directly.

Perhaps this is exactly what the SBA wanted, but at least for me it was far less in terms of “guidance” than I was hoping for.

The SBA Needs To Get It’s Act Together On The PPP

The SBA’s implementation of the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) has been a mess. The intention was to provide needed relief to businesses that were impacted economically by the COVID-19 crisis. But, while very well-intentioned, it’s implementation has been flawed. In particular, the SBA has given inconsistent guidance that continues to change and evolve, leaving companies left to wonder if they qualify or not. The result has been not just confusion but also job losses that were likely not what Congress intended the program to result in.

The SBA’s implementation of the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) has been a mess. The intention was to provide needed relief to businesses that were impacted economically by the COVID-19 crisis. But, while very well-intentioned, it’s implementation has been flawed. In particular, the SBA has given inconsistent guidance that continues to change and evolve, leaving companies left to wonder if they qualify or not. The result has been not just confusion but also job losses that were likely not what Congress intended the program to result in.

The Paycheck Protection Program was established by the CARES Act to help small businesses keep paying their workers. The program allows businesses with fewer than 500 employees to apply for low-interest loans to pay for their payroll, rent, and utilities. The program’s original $349 billion was allocated between April 3 and April 16. The second allotment of $320 billion was signed into law on April 23 and the SBA began accepting applications on April 27.

The program sparked confusion from the start. After its enactment but before it was implemented, there were questions about the SBA’s “affiliation rules” which can disqualify companies if the aggregated number of employees at affiliate companies is greater than 500. That rule was designed to prevent companies under common ownership from accessing SBA funds, but as it applied to PPP, it potentially excluded any venture-backed companies where venture firms owned greater than 20% equity (and where the companies were not affiliated, they just shared a common investor). Those rules seem to have been ironed out and there was initially a rush of venture-backed companies wanting to avail themselves of help under the PPP.

Many VCs urged caution (see my post describing Foundry’s view that companies should carefully consider if they met the program criteria for example, and a New York Times article on the subject, as just two examples), wanting to make sure that any company applying truly qualified for the money. It was always our belief that some venture-backed companies could and should apply (venture-backed companies employ about 2.7M people in the US) but it was unclear from the start which companies were (or should be) eligible. This confusion was compounded by several problems with the way the program was set up. The funds allocated by congress were limited and everyone expected the program to be oversubscribed. Secondly, the funds were to be given out on a first-come, first-served basis. This exacerbated the first issue and meant that anyone considering a loan needed to rush to apply and many companies did so without the space and time to think through whether it made sense for them. Additionally, the funds were distributed through the existing banking system – the only practical way to get that much money into the hands of companies that quickly for sure, but also leading banks to prioritize their own customers over others (see below for ways this created challenges to the fair disbursement of funds) and to their prioritizing larger loans over smaller ones.

The language of the act requires companies to certify that the uncertainty of current economic conditions makes it necessary to apply for the PPP loan to support its ongoing processes but it was not clear what “necessary” actually meant. Subsequent to this, the SBA released a series of FAQs in an attempt to clarify which companies qualified but this only served to further confuse things. In particular is the question of what “economic necessity” means for a business, which was the standard set in the original act by Congress. Particularly confusing to many companies was the statement that companies needed to consider whether they had alternative financing options. This concept was first brought up in the infamous question # 31 on one of the SBA’s FAQs that was released about a week ago. In that FAQ the SBA stated (emphasis added):

[B]efore submitting a PPP application, all borrowers should review carefully the required certification that “[c]urrent economic uncertainty makes this loan request necessary to support the ongoing operations of the Applicant.” Borrowers must make this certification in good faith, taking into account their current business activity and their ability to access other sources of liquidity sufficient to support their ongoing operations in a manner that is not significantly detrimental to the business.

The original FAQ related to public companies but was quickly extended to include private ones. Exactly what this means isn’t clear. It doesn’t appear to mean that a company needs to have a financing offer, just that they could likely raise money elsewhere; and while the PPP isn’t a “cap table protection program”, as venture attorney Ed Zimmerman has pointed out, it’s not at all clear where the bar is on alternative financings and how a company should evaluate the likelihood of its obtaining money elsewhere. Nor is it clear what that last statement means, “not significantly detrimental to the business.”

This new guidance came on the backs of some companies clearly abusing the intent of the program, if not at the time the exact language of the Act. For example, AutoNation car dealerships ($77M), Ruth’s Chris Steak House ($20M), and the Los Angeles Lakers ($4.6M). It’s understandable that public option, as well as the SBA itself, felt that the program should be clarified such that companies like these were not eligible (each of the companies above have said they will return the money).

At the same time, as I’ve written about a few times, PPP money is not getting to many of the kinds of businesses that Congress clearly intended to be helped. This is particularly true for women and minority owned businesses but also true for a wide swath of Main Street businesses that either lacked the banking relationships to access funds (which were distributed through a subset of banks in the US that were qualified under a specific SBA program) or for whom the loan program or its forgiveness element wasn’t practical. For instance, the measurement of payroll for forgiveness – a central element of the program – is 8 weeks after funds disbursement, which makes it impractical for businesses that are unable to restart their businesses in that time period (it would make much more sense to have the repayment period begin after a state’s stay at home order has been fully lifted). Additionally, the initial terms of the loan stated that the full amount of the loan needed to go to payroll, rent/mortgage, and utilities with no specific percentage of the funds going to each. Now, no more than 25% can go towards rent/mortgage and utilities.

As companies try to figure all this out, the PPP Safe Harbor has been extended to May 14 (meaning that companies can return their loans by that time and avoid any potential penalties). But we’re still waiting on final clarification on the rules, which the SBA has said is forthcoming (but have not yet been released – we’re 4 days out from the safe harbor ending). The result is confusion and quite a bit of disagreement across businesses. Many companies are trying to rely on the initial intent of the act – preserving payroll – and arguing that if they plan to reduce staff but for taking the PPP money they should qualify for the loan. That clearly isn’t the way the SBA is interpreting the Act nor how they’re guiding the business community (but it is likely closer to what Congress intended when they passed the Act). Just where the line is between need (and payroll preservation) and greed isn’t very clear. This must be clarified and done so quickly. That Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin has stated that all loans greater than $2M will be audited is adding to the pressure companies are feeling to get this right (and presumably the vast majority of those audits will have the benefit of a year or more of hindsight; it will be hard in many cases to divorce what actually happened from what a company thought was happening in real time).

The lack of clarity is causing real world challenges for businesses. In just one example, Zumasys, Inc., a California software company, has sued the SBA saying that it should not have to pay back its $750K loan since the SBA changed its rules for eligibility after their loan had been dispersed. They argue that they already spent the money for what the program was intended for and qualified based on what they understood the rules to be at the time. I’m not arguing for their case – just pointing out that 4 weeks into the program the SBAs changing guidance is causing real issues. This is a meaningful issue for companies who took money and kept people employed in good faith based on their understanding of the program at the time only now to have the rules changed on them. If a company returns the money they’re still on the hook for the payroll they incurred. Presumably (and we know this from our own direct experience) some will have to cut deeper now to compensate.

In related news, The Washington Post reported yesterday that the Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program (also administered by the SBA) has reduced their loan limit from $2 million to $150K and is only accepting applications from agricultural interests, due to its backlog.

It’s clear that the SBA is out of its depth and cannot cope with both the volume and the complexity of our country’s small business needs right now. While US entrepreneurs are the ones dealing with the clumsy handling of these loans in the short term, our overall economy will be dealing with the fallout for years.

The Changing Nature of Entrepreneurship | EforAll

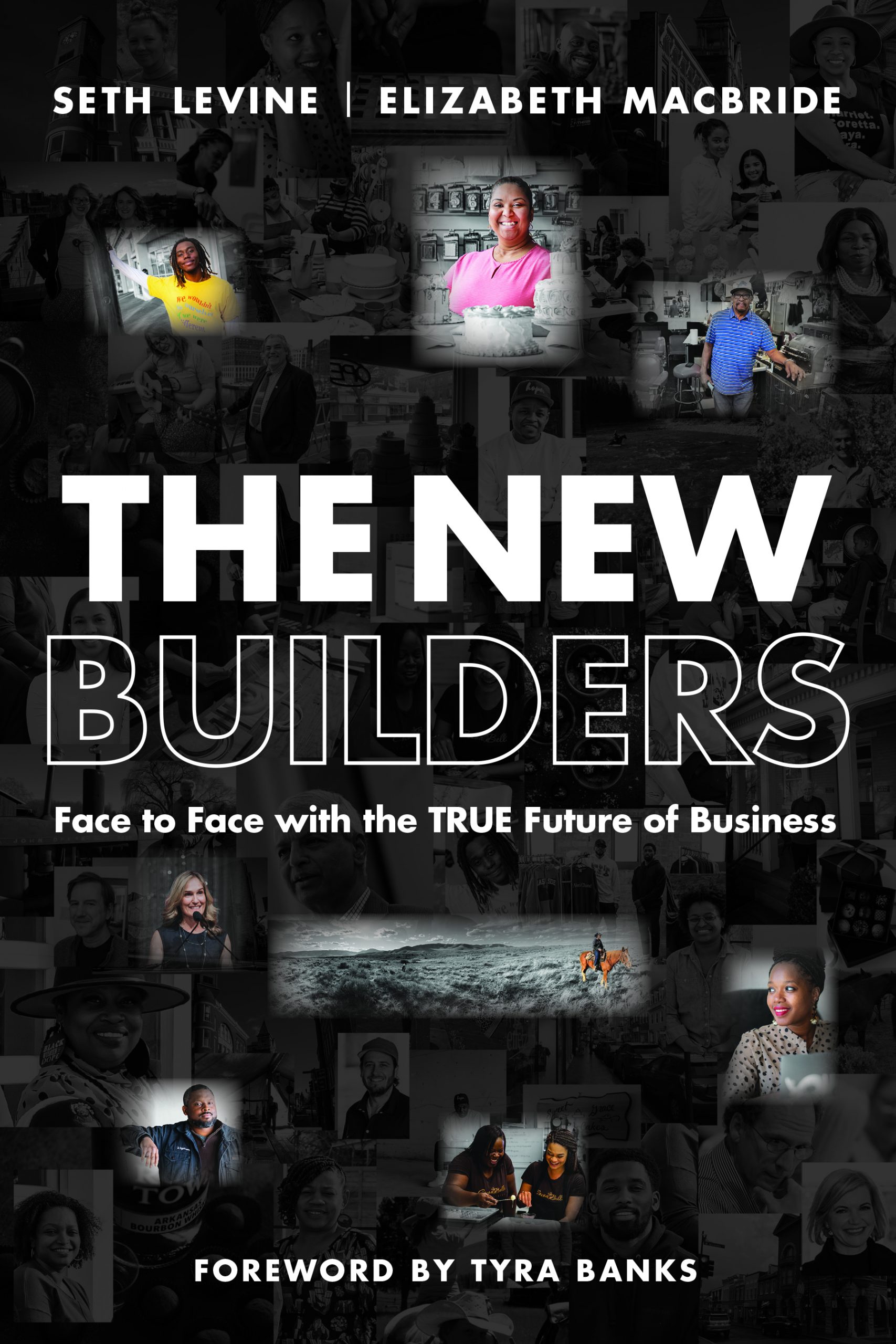

![]() Entrepreneurship in the United States is changing pretty dramatically – in ways that many of us have failed to notice or understand. Specifically today’s American entrepreneurs are more likely to be female and non-white. In fact, the number of women-owned businesses has increased 31 times between 1972 and 2018 according to the Kauffman Foundation (in 1972, women-owned businesses accounted for just 4.6% of all firms; in 2018 that figure was 40%). Meanwhile, the fastest-growing group female entrepreneurs are women of color, who are responsible for 64% of the new women-owned businesses being created. There’s a lot more to dig into here, which I’ll do in future posts. But it’s urgent that we begin to understand this because we’re failing to build systems to support these new entrepreneurs. This has become especially clear in the current economic crisis, as I pointed out in this piece I wrote with Elizabeth Macbride a few weeks ago for CNBC as well as this post from last week. Relief money authorized by congress under various programs of the CARES Act and other initiatives is failing to reach many women and minority owned businesses and is highlighting structural issues with the way we support entrepreneurs in the United States. For example, it has been widely documented that women and minority owned businesses are not accessing aid through the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) – see for example, here, here, here, here, here. This program requires businesses to have relationships with certain approved SBA lenders, which women and minority owned businesses are less likely to have. Its initial roll-out excluded certain types of financial institutions (most notably CDFIs) which disproportionately bank these businesses. It also left much of the underwriting criteria up to the banks themselves, who favored other customers. And the program itself – based on W2 payroll and primarily benefiting businesses that were in a position to open up quickly – failed to address the kinds of businesses most likely to be started by this new generation of entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneurship in the United States is changing pretty dramatically – in ways that many of us have failed to notice or understand. Specifically today’s American entrepreneurs are more likely to be female and non-white. In fact, the number of women-owned businesses has increased 31 times between 1972 and 2018 according to the Kauffman Foundation (in 1972, women-owned businesses accounted for just 4.6% of all firms; in 2018 that figure was 40%). Meanwhile, the fastest-growing group female entrepreneurs are women of color, who are responsible for 64% of the new women-owned businesses being created. There’s a lot more to dig into here, which I’ll do in future posts. But it’s urgent that we begin to understand this because we’re failing to build systems to support these new entrepreneurs. This has become especially clear in the current economic crisis, as I pointed out in this piece I wrote with Elizabeth Macbride a few weeks ago for CNBC as well as this post from last week. Relief money authorized by congress under various programs of the CARES Act and other initiatives is failing to reach many women and minority owned businesses and is highlighting structural issues with the way we support entrepreneurs in the United States. For example, it has been widely documented that women and minority owned businesses are not accessing aid through the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) – see for example, here, here, here, here, here. This program requires businesses to have relationships with certain approved SBA lenders, which women and minority owned businesses are less likely to have. Its initial roll-out excluded certain types of financial institutions (most notably CDFIs) which disproportionately bank these businesses. It also left much of the underwriting criteria up to the banks themselves, who favored other customers. And the program itself – based on W2 payroll and primarily benefiting businesses that were in a position to open up quickly – failed to address the kinds of businesses most likely to be started by this new generation of entrepreneurs.

We can and must do better.

Which is why I’d like to highlight for you a great program called EforAll. Launched in 2013 with a mission of partnering with communities to help under-represented individuals successfully start and grow their businesses, EforAll is a pretty special organization. I’ve gotten to know them well over the past two years (Brad and his wife Amy, as well as Greeley and I are financial supporters of EforAll). EforAll combines immersive business training, mentorship and an extensive support network to help support their entrepreneurs. It’s incredibly compelling and urgently needed – now more than ever. EforAll is up and running in 9 communities in Massachusetts and Colorado and, to date, they’ve supported entrepreneurs in starting almost 350 businesses, 83% of which continue to be actively pursued by their founders. About a year ago we launched in Longmont and that program just graduated their first class (I attended the virtual demo day/graduation – it was inspiring).

We’ll be starting up another Longmont program this summer and are looking for mentors in Boulder and the Front Range (although potentially for this one anywhere – we anticipate much of this summer’s program will end up being virtual). This is a fantastic opportunity to help female, minority, and immigrant entrepreneurs pursue their business ideas.

A few stats:

EforAll National

– Over 500 ventures graduated

– Nearly $35M in capital raised

– Over $25M in 2019 revenue

EforAll Longmont

– 9 businesses (11 entrepreneurs) went through first Longmont accelerator

– Those entrepreneurs were from the North Metro area, Boulder County, and Weld County

– Ventures in the first program ranged from gluten-free beer & pastries being made from ancient grains & traditional Peruvian recipes, to a financial literacy app for elementary school students, to a husband & wife duo manufacturing adaptive underwear for individuals with sensory disabilities

– Highlights from the first accelerator include an entrepreneur securing her first two grocery store clients for her plant-based meat product, an entrepreneur raising 40k from friends and family, and an entrepreneur launching their first online marketplace for disability-focused products

– EforAll Longmont was also mentioned in this href=”https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/07/your-money/entrepreneurship-philanthropy-gururaj-deshpande.html”>New York Times article, received support from Google, and worked with more than 50 volunteers during our first accelerator (including about 30 mentors)

EforAll Mentoring Ask – Mentoring with EforAll is a fantastic way to support small businesses and aspiring entrepreneurs in your own background. Accelerator Mentors come from a variety of backgrounds and use their business and leadership experience to guide new entrepreneurs through the process of starting or growing a business. Mentors work in teams of three and are matched with an entrepreneur based on schedule availability and desire to work together. The team meets as a group to help reaffirm topics and themes raised during classes, while also strategizing with the entrepreneur on how to reach their specific goals during the program. Mentoring with EforAll is a 90-minute per-week commitment from July-September and all meetings between entrepreneurs and mentors will take place virtually. For more information, you can click here and you can also email EforAll Colorado Executive Director, Harris Rollinger, at harris@eforall.org.

Colorado is Opening Up. Foundry is not. Here’s our Thinking.

In mid-March, I wrote a post about how Foundry Group had joined a number of other businesses in the early adoption of work from home and other practices to stem the spread of COVID-19. We recognized that this would be an essential part of helping create social distance and by doing so, flattening the curve.

In mid-March, I wrote a post about how Foundry Group had joined a number of other businesses in the early adoption of work from home and other practices to stem the spread of COVID-19. We recognized that this would be an essential part of helping create social distance and by doing so, flattening the curve.

As Colorado and many other states are moving to a more relaxed set of policies (although Denver and Boulder are waiting a few more weeks until they follow the rest of the state), we’ve decided that for Foundry we’ll continue our work from home policy until at least the end of May (Brad’s post on that here). We’re doing this because we’re in the fortunate position where we can and we’re being public about it because we’re hoping other businesses that are in a position to do so will do the same. We’re fortunate at Foundry to operate the kind of business that works well remotely and although we miss seeing each other in the office and the natural collaboration that happens when we’re all there, our business functions pretty much normally even when we’re all remote. And, like other businesses, we’ve been very deliberate about trying to replicate our in-office dynamic online (for us that includes several weekly stand-ups, extended time together on Mondays as well as ad hoc “cocktail/mocktail hours”. We also recognize that there are many businesses that need to open up sooner and we feel that they should take priority over companies like Foundry that can continue working from home without big disruptions to our operations.

If you are running a company that is similarly situated, we hope that you will follow suit and wait a bit longer to open up. We’re going to reevaluate opening up at the end of May and decide if it’s appropriate for us to re-open the office in early June or if we should extend our work from home time even further. The more effort we put into mitigating this crisis, the more flexibility we will have later in the summer to get things back to normal.

We’ve helped over 150 small businesses navigate the crisis | Here’s what we’ve learned

I wrote recently about the The Finance Assistance Network (FAN), that I helped set up (along with Lew Visscher and Phil Votteiro) three weeks ago to offer pro bono financial advice to small businesses affected by COVID-19. So far the network has helped almost 200 companies navigate questions around surviving in the post-Covid work and to access PPP and other federal assistance. Tomorrow (Friday, May 1) at 9:00MT the FAN is hosting a webinar – Extending Your Runway: Small Business Tools to Survive a Cash Flow Crisis. The webinar is hosted by Good Business Colorado and is sponsored by a number of organizations advocating for small businesses including MAPR Agency, The Bell Policy Center, Small Business Majority, and others. The webinar is free and you can register here. I’m encouraging everyone to share the information about the webinar and the FAN on their social media channels and especially with small business owners in their networks. Supporting small businesses during this crisis is crucial to the overall health of our economy so please spread the word about these free resources.

I wrote recently about the The Finance Assistance Network (FAN), that I helped set up (along with Lew Visscher and Phil Votteiro) three weeks ago to offer pro bono financial advice to small businesses affected by COVID-19. So far the network has helped almost 200 companies navigate questions around surviving in the post-Covid work and to access PPP and other federal assistance. Tomorrow (Friday, May 1) at 9:00MT the FAN is hosting a webinar – Extending Your Runway: Small Business Tools to Survive a Cash Flow Crisis. The webinar is hosted by Good Business Colorado and is sponsored by a number of organizations advocating for small businesses including MAPR Agency, The Bell Policy Center, Small Business Majority, and others. The webinar is free and you can register here. I’m encouraging everyone to share the information about the webinar and the FAN on their social media channels and especially with small business owners in their networks. Supporting small businesses during this crisis is crucial to the overall health of our economy so please spread the word about these free resources.Early Monday morning, the Small Business Administration’s application system for its second round of PPP funding crashed within an hour of coming online. The first round of $342 billion — nearly ten times what the SBA administers in a typical year — was depleted in just 13 days. And like the first round, this latest infusion of $310 billion will be delivered on a first-come, first-serve basis.

Getting money into the hands of small businesses is a good idea, and we applaud the government’s quick actions. However, in the haste to create and pass these two rounds of emergency financial support, there are some gaping holes that must be addressed quickly so companies can make the most of these lifelines and extend their financial runways.

According to data released by the SBA, the average PPP amount was just over $200,000. That equates to a nearly $100,000 monthly payroll — hardly “main street” businesses. For companies reliant on PPP funding as a lifeline for operational survival, the stakes for accessing and using this funding wisely could not be more high.

How high? A just-released survey from Goldman Sachs finds that nearly 70% of small businesses will likely change their business models for good as a result of COVID. In other words, if companies are relying on the same strategies that they had in place in January to keep their doors open, the ability to adapt and update practices now has an even greater urgency. Even in good times, most small businesses carried between one to three months of cash reserves. More than ever, understanding and then extending financial runways for small businesses is a critical component to helping businesses survive.

A little less than three weeks ago, we helped create the Finance Assistance Network, a pro bono alliance of senior financial professionals, supported by legal, HR and other resources that are available for free to any small business or nonprofit organization impacted by COVID, regardless of size or location. The network connects business owners with a small army of CFOs, controllers and senior financial professionals willing to help with business and cash flow planning, applying for PPP and EIDL money and urgently needed support.

Since launching earlier this month, the network has helped more than 150 companies, giving us unique insights into the special challenges and limitations of the CARES Act. For example, the companies we’ve helped appear to be especially impacted by the eligibility criteria for PPP funding because the programs exclude many small businesses that can benefit the most from this support.

Many small businesses rely on consultants and part-time 1099 workers who do not appear on payroll calculations (they can apply as individuals to the program, although anecdotal evidence is that few are), which can hurt their chances for larger loans. Likewise, businesses owned by women and people of color are at special risk of being excluded from PPP funding because they are more likely to make use of contractors and less likely to have established relationships with SBA approved banks.

The feedback that we hear most frequently is that the calculations of payroll are far too small to provide the stabilization needed for ongoing survival and continued operations. Many small businesses have expenses, such as rent and utilities, that are significant relative to their payroll costs. By stipulating that funds need to be spent on payroll to qualify for forgiveness and by covering only an 8-week period, the current program effectively acts as federal unemployment insurance, rather than a business stabilization program.

Our biggest takeaway is that companies need more flexibility in how they spend aid dollars to balance what’s in the best long-term interest of their business and in the best interests of their employees. Many employees will likely be out of work well past the 8-week period anticipated by Congress, and some are better off individually taking enhanced unemployment benefits.

This Friday, we are partnering with Good Business Colorado to put on a free webinar, open to all, to share how companies of all sizes should be thinking about approaching business planning through the crisis. We’ll also discuss how they can access the pro bono resources provided by the Finance Assistance Network, apply for PPP and other loans and get expert guidance on using these funds to help your company extend your financial runway. Please join us by registering at https://bit.ly/3bM3OPg.

Seth Levine is a partner at the Foundry Group. Lew Visscher is the founder of Lew’s List. Phil Vottiero is a partner at High Plains Advisors. Together, they are the founders of the Finance Assistance Network, a pro bono network of more than 100 senior finance professionals who have come together to help businesses navigate and survive the COVID-19 crisis.

The Week 6 Slump

I wrote a couple of weeks ago about settling in and some of the challenges of accepting what is now our new normal. Covid-19 has completely upended everyone’s life and created a massive amount of uncertainty. But, at the time, I wrote that it felt like things were starting to settle in – that many were getting used to their new routines and accepting, if not embracing, the lack of clarity around the future. Rolling forward to this week and it feels like this has changed a bit – at least temporarily. During a number of conversations this week, I’ve noticed a difference in how people are feeling, and to the acceptance that I think most of us had internalized up until now.

I wrote a couple of weeks ago about settling in and some of the challenges of accepting what is now our new normal. Covid-19 has completely upended everyone’s life and created a massive amount of uncertainty. But, at the time, I wrote that it felt like things were starting to settle in – that many were getting used to their new routines and accepting, if not embracing, the lack of clarity around the future. Rolling forward to this week and it feels like this has changed a bit – at least temporarily. During a number of conversations this week, I’ve noticed a difference in how people are feeling, and to the acceptance that I think most of us had internalized up until now.

People have started hitting a wall.

Frustrations are coming from different places: There is uncertainty about when we might be able to start moving around more freely. There is conflicting advice about when and how things will open up (in Colorado for example, the state has one set of guidance, my county has another set; other states are already open while California has said they’ll be closed through at least June 1st; and to add to that confusion there is zero guidance and leadership coming from our national government). Parents, many of whom have been trying to balance work, parenting and being school teachers, are getting frustrated and worn down; on top of that, they don’t know what’s coming this summer and if their kids will be able to go to camp. Everyone has a certain sense of being tired of the same scenery every day as well as a continued overarching concern about others in our community and about our economy more generally (today’s GDP news was just a harbinger of what will be unprecedented contraction when the Q2 numbers come out). Many of us now know people who have not only gotten sick from COVID-19 but know someone who lost a family member or close friend. And on top of all of that is the lack of clarity about when things will really begin to change (my partner Brad wrote an excellent post on the disorientation this is causing a few days ago).

I think it’s important to acknowledge that this monotony and constant worry is hard. Given how frequently I’ve heard people talk about this this week, I’ve started calling it the “Week 6 Slump”. I don’t know what the magic is about week six but if you’re feeling this way, you’re not alone. And while I know we still have weeks – perhaps months – of this left, I do know we’ll get through it. Hang in there.

PPP and Women and Minority-Owned Businesses – We Need To Do More

I’ve published a number of posts over the past few weeks about some of the challenges of the existing PPP loans and in particular, about my concerns that the loans aren’t getting to as many of the smaller businesses that need them. In this CNBC op-ed article, Elizabeth McBride and I pointed out how the face of entrepreneurship in the United States is changing. Specifically, the number of women-owned businesses has increased 31 times between 1972 and 2018 (in 1972, women-owned businesses accounted for just 4.6% of all firms; in 2018 that figure was 40%), according to the Kauffman Foundation. But the aid programs are largely failing to address the needs of these key entrepreneurial communities and the PPP loans are not getting broadly distributed across these demographics. The pressure on Main Street entrepreneurs is being compounded by the current economic crisis in ways that we haven’t even begun to wrap our heads around. Businesses started by women and minorities are more likely to have been impacted by the crisis and we fear will be the last to recover from it. According to the Center for Responsible Lending, a large majority of Black, Latino and other minority-owned businesses stand close to no chance of receiving a PPP loan through an SBA-approved bank or credit union. With loan sizes pegged to payroll, women and minority-owned businesses – which on average employ fewer people and as a result have smaller payrolls – are being de-prioritized by the banks that are the gatekeepers of the program. Compounding this problem, women and minority-owned businesses are also more likely to use contract or 1099 labor, which the PPP loan calculations exclude for purposes of calculating eligible loan size. And more fundamentally, these entrepreneurs are less likely to bank with an SBA approved lender. Even when they do bank with an SBA lender, there is evidence that these lenders are favoring their larger “small business” clients (for example, the average loan size in the initial PPP program was over $200k, representing businesses with payroll of around $1M / year).

I’ve published a number of posts over the past few weeks about some of the challenges of the existing PPP loans and in particular, about my concerns that the loans aren’t getting to as many of the smaller businesses that need them. In this CNBC op-ed article, Elizabeth McBride and I pointed out how the face of entrepreneurship in the United States is changing. Specifically, the number of women-owned businesses has increased 31 times between 1972 and 2018 (in 1972, women-owned businesses accounted for just 4.6% of all firms; in 2018 that figure was 40%), according to the Kauffman Foundation. But the aid programs are largely failing to address the needs of these key entrepreneurial communities and the PPP loans are not getting broadly distributed across these demographics. The pressure on Main Street entrepreneurs is being compounded by the current economic crisis in ways that we haven’t even begun to wrap our heads around. Businesses started by women and minorities are more likely to have been impacted by the crisis and we fear will be the last to recover from it. According to the Center for Responsible Lending, a large majority of Black, Latino and other minority-owned businesses stand close to no chance of receiving a PPP loan through an SBA-approved bank or credit union. With loan sizes pegged to payroll, women and minority-owned businesses – which on average employ fewer people and as a result have smaller payrolls – are being de-prioritized by the banks that are the gatekeepers of the program. Compounding this problem, women and minority-owned businesses are also more likely to use contract or 1099 labor, which the PPP loan calculations exclude for purposes of calculating eligible loan size. And more fundamentally, these entrepreneurs are less likely to bank with an SBA approved lender. Even when they do bank with an SBA lender, there is evidence that these lenders are favoring their larger “small business” clients (for example, the average loan size in the initial PPP program was over $200k, representing businesses with payroll of around $1M / year).

I recently published some recommendations that I sent to several members of congress to consider (some of these made it into the Federal Stimulus Package passed this last week). Included in it were some ideas that were specific to this point including the potential for a specific rural allocation of funds as well as including CDFIs in the program. I was happy to see that Congress specified $60 billion targeted at smaller banks (with the idea that these banks serve more small businesses). I was also happy to see CDFIs explicitly included in this 2nd traunch of the PPP program (these institutions are key avenues to funding these lesser served businesses). However, none of this is really enough, given the importance and relative size of women and minority-owned businesses in our entrepreneurial ecosystem. I plan to continue to work on this but I wanted to flag it to readers as an area of federal support that is significantly lagging. Unfortunately what hasn’t been addressed is the expansion of the program beyond “paycheck” and beyond the initial 8 week period of coverage that has initially been addressed. In the case of most main street and small businesses, calculations of payroll are far too small to provide the stabilization that these businesses need (many small businesses have expenses such as rent and utilities that are significant relative to their payroll costs). Further, by stipulating that funds need to be spend on payroll to qualify for forgiveness and by covering only an 8-week period, the current program effectively acts as a Federal unemployment insurance, rather than a business stabilization program. Companies need more flexibility in how they spend aid dollars to balance what’s in the best long term interest of their business (i.e., survival) and the best interests of their employees (many of whom will be out of work well past the 8 week period anticipated by Congress and some of whom are better off individually taking enhanced unemployment benefits).

Related to all of this, we’re putting on another webinar through the Financial Assistance Network (see the Network announcement here). We’re partnering with Good Business Colorado, The Bell Policy Center, Best for Colorado, as well as a number of other organizations and are especially targeting women and minority-owned businesses. You can register for the webinar here. I’d appreciate you sharing this with your networks to get the word out. The FAN network has already helped over 150 businesses but we have plenty more capacity and I’d like to see this number grow significantly, especially in light of the data that’s coming out showing just how many businesses haven’t been able to unlock federal aid and the number of companies struggling with key decisions that may literally effect their survival. Let’s give these businesses and the entrepreneurs behind them as much support as we can.

Extending and Expanding Aid – Some Policy Ideas

I was recently asked to put together some ideas for consideration for the next economic package that congress is currently working through and which I hope will both extend existing programs put in place to dampen the blow of the economic crisis brought on by Covid-19 but also extend that aid to critical areas of the economy that aren’t yet being supported by current programs. I touched on some of the issues in two OpEd pieces I co-authored with Elizabeth Macbride in the last two weeks (here and here in case you missed them). There wasn’t space in those to really flesh out a number of ideas that I think are worth thinking about, and I was only in the process at that point of putting this together. I leaned on a number of people for their advice to come up with what I describe in more detail below. Specifically I’d like to thank Doug Rand, Delaney Keating and Dan Caruso for their input. I’ve had some discussions about this with members of congress and am hopeful that at least some of these ideas will be considered in the upcoming 4th aid package. I’d love your feedback (as well as other ideas). I have an ongoing line of communication in congress about these and other ideas. Overall, despite the size and scale of the existing aid packages, I think more needs to be done to help prop up the economy and especially to target some of the businesses that need and deserve help but are being left behind by the current programs.

I was recently asked to put together some ideas for consideration for the next economic package that congress is currently working through and which I hope will both extend existing programs put in place to dampen the blow of the economic crisis brought on by Covid-19 but also extend that aid to critical areas of the economy that aren’t yet being supported by current programs. I touched on some of the issues in two OpEd pieces I co-authored with Elizabeth Macbride in the last two weeks (here and here in case you missed them). There wasn’t space in those to really flesh out a number of ideas that I think are worth thinking about, and I was only in the process at that point of putting this together. I leaned on a number of people for their advice to come up with what I describe in more detail below. Specifically I’d like to thank Doug Rand, Delaney Keating and Dan Caruso for their input. I’ve had some discussions about this with members of congress and am hopeful that at least some of these ideas will be considered in the upcoming 4th aid package. I’d love your feedback (as well as other ideas). I have an ongoing line of communication in congress about these and other ideas. Overall, despite the size and scale of the existing aid packages, I think more needs to be done to help prop up the economy and especially to target some of the businesses that need and deserve help but are being left behind by the current programs.

PPP Program– Expand the program beyond the current $349Bn, of course. There is talk of another $250Bn. That won’t be enough.– We need a version of the program that isn’t payroll based and where the forgiveness isn’t based on future payroll (for example, restaurants won’t qualify for loan forgiveness if they can’t open up by June).– Consider a separate loan program for very small businesses (fewer than 10 or 20 employees) that’s based on a revenue formula and so long as they use the funds for current expenses (i.e., paying rent, utilities, employees – including 1099 employees; but excluding things like inventory or capital expenditures) they’d qualify for loan forgiveness– We need distribution mechanisms beyond the SBA (which is overwhelmed). Consider for the smallest businesses using PayPal, Square or others for the distribution of funds (some of this started happening last week, which is good).– We should also fund the CDFIs to participate in community lending programs (could be structured as grants with specific parameters/limits). I don’t really understand why CDFIs were left out of the original program to begin with (presumably because they’re considered “Democratic” institutions?).CDFI Expanded Role (in addition to what I describe above re: PPP)– The CDFI infrastructure already exists and is relatively efficient at distributing funds to underserved communities – per the last bullet point above this program could easily be expanded (and was left out entirely of prior aid packages).– Create a Public Health Financing Program to ensure that underserved communities are prepared to respond to COVID-19 and other emerging health threats. CDFIs should be given a resources to promote the establishment and growth of local public health providers, including walk-in clinics, pharmacies, and nursing services. This would both create economic development in communities where it is much needed but would also help shore up against the likely expansion of Covid-19 into rural communities that have, to date, been relatively spared from the virus (but we know it’s coming).– This could be primarily accomplished by steering New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) incentives toward investment in public health facilities in underserved areas. The Treasury Department’s Community Development Financial Institutions Fund is responsible for the NMTC, as well as financial and technical assistance for designated institutions.– New resources could also be mobilized through the USDA’s various rural development programs and the Community Economic Development (CED) program within HHS.– A comparable approach was taken in 2010, when Treasury, USDA, and HHS jointly launched the Healthy Food Financing Initiative to address food deserts in underserved communities. This initiative was later written into Congressional appropriations.Expand the Existing SBIR Programs– Rapidly execute new SBIR awards.– Congress could provide a supplemental appropriation, allocated proportionally among agencies that already participate in the SBIR program.Expand the SBA Microloan Program– The SBA Microloan program works through nonprofit intermediaries to provide technical assistance and loans of up to $50,000 to small businesses and nonprofit child care centers. The program targets women, low-income, veteran, and minority entrepreneurs. In FY2019, SBA made 53 loans to intermediaries, which in turn provided over 5,500 microloans totaling $81.5 million. The average microloan was $14,735 with a 7.5% interest rate. Unlike the 7(a) program, which supports larger firms acquiring hard assets, by far the most common use of microloans was working capital (73%).– Most entrepreneurs are not eligible for standard SBA loans because they lack business or personal assets—especially minority-owned entrepreneurs. The successful Microloan program should be expanded significantly, so that it becomes a core tool in addressing this inequitable capital gap. This would require expanding eligibility for intermediary lenders and raising the aggregate loan limit from $6 million to at least $50 million for top performers as well as expand program eligibility (see next point)– Congress should also open up the Microloan program to for-profit and nonprofit small entities alike, rather than restricting nonprofit participation only to child care centers. This would empower social entrepreneurs to solve local problems, including public health challenges that are particularly acute during an epidemic.– Consider a rural allocation for this Microloan expansion (and consider distributing rural funds through local, community banks).– Another consideration is to push funding to communities who establish “community loan funds” to cycle those investments long term from within and encourage the further development of such funds. Perhaps offer tax incentives or other incentives for communities and investors to put these funds together.Other Ideas– This has a longer lead time but we should use this time as a chance to invest much more heavily in rural broadband infrastructure. Will be a nice job creator for the infrastructure providers but more importantly will blunt the impacts of the next virus outbreak as people will be more able to work remotely.– On a related note, expand the E-Rate program which brings fiber to schools to include hospitals and other medical infrastructure. Clearly tele-medicine is going to be important in any future viral outbreak but this also feels like an area of the economy that can and should change coming out of this current crisis.