Saying "no" can be hard to do

At the risk of opening myself up to a landslide of snide comments expressing sympathy for the "difficult" job a VC has saying no to so many potential investments, but in the interest of being open about the experience of venture capital from the inside I offer up the following thoughts:

Sometimes it’s very easy to decide to decline a company’s request for financing (and we see literally thousands of plans a year, so we’re pretty well practiced at it). Many times the company simply isn’t a fit for our investment focus (we get a few "invest in our [pick one] manufacturing/car wash/custom painting/etc business" requests ever year). Or the business plan is clearly off base (my personal favorite from this genre was the company that planned to colonize the moon for the purpose of reducing the cost of launching satellites – which they were going to build from materials they were to mine from the moon). Lots of others are potentially interesting but for one reason or another just don’t make the cut. The ones that pique our interest we start a dialogue with, which typically involves several meetings, background due diligence, etc. Some of these businesses we will relatively quickly decide are not a good fit and they fall off the list. Then there are the ones that we really dig into. While we pride ourselves on moving quickly through our investment process, being quick doesn’t mean not being thorough – we do a lot of work looking into investment opportunities before we make our final decision to invest.

As we’re moving through this process there continue to be a meaningful percentage of companies that we ultimately decide not to pursue an investment in. I like to think our process is a pretty open one (specifically that we’re very clear with the entrepreneurs that we’re working with what our outstanding questions/areas of concern are). But even when it’s clear that we’re just not "there" on a deal it can be difficult to turn down an investment late in the game. I’m not talking about reaching the decision to say no – we have a well exercised process and a very open patter of communication at Foundry that I think allows us to make very good decisions throughout our deal process. I’m talking about actually making the phone call to someone you’ve been working with for months, who has been answering your questions, putting up with your requests for more data and with whom you’ve likely been engaged in pretty detailed business planning.

I had a particularly challenging example of this about a month ago when I turned down an investment in a company that I was really close to saying yes to. In this case I particularly liked the founder (we had both a great personal and professional connection) and the business was in an area that I know extremely well. I did a ton of work on the opportunity and as a partnership we had many conversations about the business (while I had been leading the work all of my partners had spent real time looking into the business and had met the founder several times). Ultimately I couldn’t get over a handful of concerns about where the market (and in this case specifically competition) was moving and as a result turned down the chance to invest. Probably the hardest "no" that I’ve ever had to give . . . .

Note: the company in question had another source of funds and is off and running on executing against their plan.

Trump’s Legacy of Racism

As I listened to Kamala Harris and Joe Biden give their speeches from Wilmington on Saturday, I was struck by the contrast they offered to the rhetoric we’ve heard coming out of the White House for the past 4 years. Perhaps I had forgotten what ‘normal’ actually was. Both Biden and Harris spoke to the entirety of America – those that voted for them and those that didn’t. They spoke of character, honesty, science, and a belief that our strength comes from collective action, not from divisiveness. I woke up Sunday morning, as I imagine many of you did, with the feeling that a weight had been lifted from my shoulders. That, while America remains surprisingly divided, we’re back on the right track. I was struck by the outpouring of pure emotion we saw, not just from around America but from around the world. It will clearly take us years to heal from the divisiveness, hatred, and animosity that our soon-to-be former president stoked and thrived on. And without question, there are voices around the country who feel marginalized and that they have been left out. We need to acknowledge that and understand why 70 million people believed that the right conduit for their voice was a racist, bigoted, selfish, lying autocrat.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the legacy Trump leaves behind – especially his legacy of racism and hatred – and wanted to share a story to put some of that thinking into context.

Trump took bigotry and hatred, that had clearly been simmering just below the surface in this country for centuries, and brought to a boil. He made it acceptable and seemingly righteous to be racist, sexist, homophobic, and generally intolerant (if not malicious) towards anyone that is somehow “different.” And while I think it’s a mistake to paint all Trump voters with a broad brush, certainly a vote for Trump was at least a statement that these things weren’t a deal-breaker. It’s ok to vote for a racist, as long as you get X (whatever that thing is that you think is more important than character and integrity).

Last week, our family dealt with a situation that was a reminder just how harmful this embracing of racism and intolerance has been to our society.

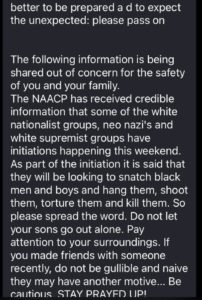

Late Thursday night, around 11 pm, we received a call from our daughter. She had been alerted by a well-intentioned friend that the NAACP was circulating a warning that white supremacist groups were plotting to kidnap black men and boys with the intent to torture and kill them. She was worried about her brother, who is black, as well as her friends at school who are black and brown. I can’t tell you how upsetting it is as a parent to know your child is up late at night worried about themselves and their family because they are targets simply because of the color of their skin.

Late Thursday night, around 11 pm, we received a call from our daughter. She had been alerted by a well-intentioned friend that the NAACP was circulating a warning that white supremacist groups were plotting to kidnap black men and boys with the intent to torture and kill them. She was worried about her brother, who is black, as well as her friends at school who are black and brown. I can’t tell you how upsetting it is as a parent to know your child is up late at night worried about themselves and their family because they are targets simply because of the color of their skin.

As parents of two black children, we’ve learned a lot about the state of race in our country in a way that our privileged, white upbringing (even in liberal households) didn’t allow us to understand. When a family of black children refers to “the talk,” they’re not talking about the birds and the bees. They mean the talk that black families have, to tell their children to watch out. To be careful about how they interact with people in authority. To explain to them that they will likely be targeted (pulled over by police, followed, etc) because of the color of their skin, but that they need to be careful in diffusing those situations, lest they be in harm’s way (like somehow this racism is their fault). We’ve already seen our kids be followed and targeted because of the color of their skin. In our family, we had “the talk” when our son was just 8 and our daughter was 11 (tbc, the talk is an ongoing conversation, not a one-time thing; over and over we’re forced to confront a racist society and racist acts and put them in context for our family).

And I can say unequivocally that overt racism has increased since Trump was elected. He didn’t invent racism, but he made it great again (to use his marketing term). We’ve experienced it as a family. Our kids have experienced it. So many others, too. I was recently talking to a black friend, a woman who has lived in Georgia all her life. She said the same thing. In 45 years she had never been called the n-word. The week after Trump was elected she was. And then repeatedly over the course of the last 4 years. Trump awakened something that was just under the surface of our society. And it’s not going to go away just because he is no longer president.

The supposed NAACP alert that our daughter sent to us turned out to be a hoax. It felt off when we saw it due to the language used, and when we looked online it turned out to be false. The idea that this warning was valid was completely plausible, given the social climate we’ve been living in and the hype we saw in the media over the past several weeks about potential election-related violence. And no doubt there were people out looking to do harm to those that they felt had caused their guy to lose the White House. While many people reading this are likely a few steps removed from the realities of what this really means to many people in our society, I wanted to share this story to provide a bit of direct and real world context. We were up that night thinking about whether our kids are safe, only because of the color of their skin, and sad and disheartened that they are afraid. Black parents (and other parents of black and brown children) around the country have to think about this all the time. That fact shouldn’t be news for anyone. Being white (and male), I can only scratch the surface of understanding what it really feels like to be a minority in the U.S.

How To Get a Job In Venture Capital

One of the most frequent questions I get asked is “how do I get a job in venture?” In fact, I’ve written two posts over the years on this topic – one way back in 2005 and a follow-up to that a few years later in 2008 (the 2nd of the post is the more practical advice if you’re pressed for time; or just keep reading below). A lot has changed in the past 10 years since I wrote my most recent post on this subject. And a lot hasn’t. Below is an updated overview of the venture job landscape as well as some current thoughts on how to break into the industry.

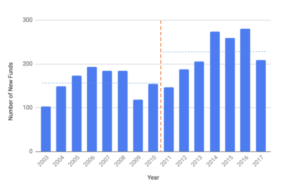

First some stats to outline the landscape. If you’re trying to break into venture the news, in general, is good (the two charts below were pulled from a great post by Eric Feng on the state of the VC market from late last year). The number of new venture firms raising their first fund has increased markedly – especially since 2011 (new funds are a good barometer of the growth of the industry, and a leading indicator of job growth in venture capital).

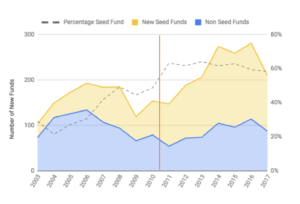

It’s interesting to note that the majority of these new funds are focused on Seed stage investing (not surprising if you follow the market, although investments at the Seed and Seed + stages have started to decline quite a bit from their peak a few years ago).

It’s interesting to note that the majority of these new funds are focused on Seed stage investing (not surprising if you follow the market, although investments at the Seed and Seed + stages have started to decline quite a bit from their peak a few years ago).

So the venture landscape has changed quite a bit since my first post on breaking into venture almost 15 years ago. So has the typical profile of a venture professional. When I first got a job in venture (now we’re going way back – that was 18 years ago) the typical venture analyst had spent 2 years in an investment banking program (maybe, but less likely, a consulting company) and spent a lot of time on the business end of spreadsheets. A venture associate had that same background, had likely worked at a venture firm as an analyst and gone back to business school. Venture principals (VPs, junior partners or other similar titles) were former venture associates who had worked their way up the chain. And partners were former junior partners who had been promoted up as well. Occasionally partners were former successful CEOs who joined the firm that backed them – at the time the most likely way to get into venture w/o having come up the ranks. In fact the hierarchy was so well entrenched, I remember at least one firm when I was applying to be an associate telling me that they’d only consider me for an analyst position because I lacked an MBA (the job I was leaving was running a $55M division of a public company with over 200 people reporting up to me; I had spent the 5 years before that managing teams of various sizes around corporate development, planning, investor relations, etc. But that experience didn’t matter at the time relative to my lack of a business degree. Needless to say, I turned down the offer to interview for that analyst position).

So the venture landscape has changed quite a bit since my first post on breaking into venture almost 15 years ago. So has the typical profile of a venture professional. When I first got a job in venture (now we’re going way back – that was 18 years ago) the typical venture analyst had spent 2 years in an investment banking program (maybe, but less likely, a consulting company) and spent a lot of time on the business end of spreadsheets. A venture associate had that same background, had likely worked at a venture firm as an analyst and gone back to business school. Venture principals (VPs, junior partners or other similar titles) were former venture associates who had worked their way up the chain. And partners were former junior partners who had been promoted up as well. Occasionally partners were former successful CEOs who joined the firm that backed them – at the time the most likely way to get into venture w/o having come up the ranks. In fact the hierarchy was so well entrenched, I remember at least one firm when I was applying to be an associate telling me that they’d only consider me for an analyst position because I lacked an MBA (the job I was leaving was running a $55M division of a public company with over 200 people reporting up to me; I had spent the 5 years before that managing teams of various sizes around corporate development, planning, investor relations, etc. But that experience didn’t matter at the time relative to my lack of a business degree. Needless to say, I turned down the offer to interview for that analyst position).

Today the market is quite different and people from a much wider variety of backgrounds are finding their way into venture. And with more, smaller, seed focused funds, VC firms can be scrappier and more thoughtful about who they want to hire and how and where they find them.

So with that good news, here are a few current thoughts on how to break into venture:

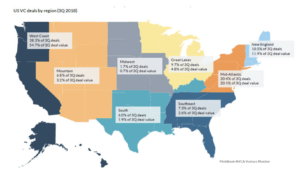

Take the long view. Despite the relative increase in number of venture firms, there still aren’t all that many jobs in venture. And they continue to be concentrated on the coasts to a large extent (see the chart that shows the data from Q3 2018 – generally representative of where the market is at the moment). Embrace that it’s a long shot and enjoy the journey. Which is to say that the things that will prepare you for, and expose you to, a job in venture are things that are generally helpful to you in any career that is focused on entrepreneurship and startups. Not getting a job in venture may be the best thing that happens to your career.

Get involved in your community. Venture and entrepreneurship aren’t spectator sports and are best experienced from within. Most cities now have various local tech meetups, pitch competitions, angel groups, etc. Get out there and participate. If you can, help organize and become a leader in your community (great entrepreneurial ecosystems are inclusive and have many leaders). If you’re interested in startups this should be both fun and easy. Make your presence known and appreciated. Find a gap in your market or someone or something that needs help and get after it. You’ll not only be helping your community, you’ll be making a name for yourself.

Get involved in your community. Venture and entrepreneurship aren’t spectator sports and are best experienced from within. Most cities now have various local tech meetups, pitch competitions, angel groups, etc. Get out there and participate. If you can, help organize and become a leader in your community (great entrepreneurial ecosystems are inclusive and have many leaders). If you’re interested in startups this should be both fun and easy. Make your presence known and appreciated. Find a gap in your market or someone or something that needs help and get after it. You’ll not only be helping your community, you’ll be making a name for yourself.

Get involved in companies. There are lots of great ways to help out companies directly. Hopefully through your work above you’ll be meeting lots of interesting people and companies. Do your best to help them out. Depending on your skill set and level of experience you may be able to offer your services directly to companies (we have plenty of people do this through Techstars for example). Figure out a way to connect interesting people together. Work your network.

Network. Most people are terrible networkers. They treat networking transactionally and they are always looking to take from their networks vs. give to them (good networkers adhere to the #givefirst mentality). Become a better networker and actively work to build out your network – of course including your local venture community as much as you can. This will pay dividends no matter where your career ends up taking you. If you do it well you’ll learn to love it (at least I hope you will). Here are two posts with some basic networking ideas to get you going (here and here).

Engage. Lots of venture capitalists put out a lot of content and it’s never been easier to engage with the venture community. Comment on blog and Medium posts, follow VCs that you respect on Medium and Twitter, send them ideas and thoughts on what they’re writing about and investing in. Stay active and top of mind. There are virtual communities in the comments sections of some venture partner and venture firms blogs. Participate. Personally I have long standing relationships with people who regularly email me with thoughts and ideas that are relevant to Foundry and our investment focus. Like most VCs I’ll take the time to engage and respond to people who are genuine in their outreach and especially those that are trying to be proactive and helpful. My favorite response to people who ask me “what can I do to help you” is to ask them to send me anything they find that’s interesting and piqued their interest (not necessarily venture or startup related). My Pocket reader is full of articles and stories that are sent to me this way. I know many other VCs do the same. It’s a genuine way to start to build relationships.

Look for any way in. Your first job in venture is typically the hardest to get. As more firms are expanding the roles they play with their portfolio, look for different ways in. Many firms now have operational groups that provide services to their portfolio companies. There are a growing number of firms that have someone running “platform” or “engagement” to better connect their portfolio CEOs. More broadly, there are plenty of non-traditional firms out there (not captured in the data above) that are investing either private, foundation or corporate money. In some cities there are organized angel groups that make use of part-time help to make investment decisions. Any job that gets you exposure to making investment decisions or helping those that do will be a good first step into venture.

Work for a startup or start one of your own. This was true 10 years ago and it remains true today. A great path into venture can be to start your own business or work for a startup. It’s a great skill-set to have and will likely put you in contact with the venture world.

Invest if you can. With investment becoming slightly less regulated there are opportunities to put even modest amounts of money to work through platforms like AngelList and others. If you have the ability, it’s not a bad way to show an interest in investing and give you something to talk about in your networking. Obviously this requires at least some amount of capital and I’m not suggesting that it’s a prerequisite to get a job in venture. But if you can do it, it’s a great way to build a mini-portfolio and may lead in unexpected directions.

Persevere. Getting a job in venture is hard and can take a while. Likely it won’t happen. Keep the long game in mind, have fun while you’re going through the process and keep at it. And maybe along the way you’ll end up finding something even more exciting to pursue and forget you ever wanted a job in VC in the first place…

Am I just a greedy VC?

My partner Jason has an impassioned post up about the carried interest debate currently taking place in Congress. No matter how you feel about Congress’ efforts to change the tax classification of VC profits from capital gains to ordinary income it’s worth a read (and keeping an open mind).

Obviously this issue is important to me and to all VCs. And while I know there are differences of opinions on the subject (clearly given the intense debate going on right now) I think Jason does a nice job of talking through the personal (this feels overstepping), professional (there are other markets where innovation is taking place where investor are actually being completely exempt from taxes that will draw talent away from the US) and legal (how do you differentiate between a VCs partnership interest from other partnership interests not subject to the proposed tax change?) arguments against the tripling of tax on the long term profits of investors.

While I wouldn’t say that I’m a “fan” of government, I’ve always been of the mind that some level of government safety-net is appropriate. I’m even, generally speaking, ok with a progressive income tax and as a relatively high wage earner understand that I have a certain burden living in our society to pay a much greater share of the overall tax burden. I point this out not to get into a political debate about the benefits of taxes, the proper level of tax or even the correct taxing system but to be clear that my views on carried interest are not part of some larger agenda around reforming the tax system or eliminating it all together.

I have many of the same concerns that Jason outlines in his blog post about the move to change the tax treatment on carried interest. I’ve even considered whether the change will either shorten or radically change my own career path.

But as a capitalist and a realist I’d simply point out that taxes shape behavior. Our tax code has examples of this everywhere. Want people to buy houses? Allow them to write off their home mortgage (but don’t let them write off credit card debt – we don’t want consumers to have too much of that…). Want people to give to charity? All them to write that off too. Want to encourage longer-term investing? Tax that at a lower rate than short term investing. Need to encourage people to save for retirement? That’s a good one for tax exemption. Invest in education? Check on that one two.

My point is that tax code changes have real world economic and behavioral consequences. And the consequence of tripling the tax on the carried interest of investors will be decreased investment, less innovation and fewer jobs (and I would guess an overall reduction in tax receipts given the 2nd and 3rd order effects of the measure – which completely defeats the purpose of the proposal which is 100% to raise revenue and “fund” the extension of other tax initiatives).

The US currently leads the world in the innovation economy. From our universities, to our entrepreneurial ecosystem, from the belief that it’s ok to step out and try, even if you fail, to our system for nurturing and funding companies, we have a huge global competitive advantage in innovation that has lead to some of the greatest advances in modern society coming from within the US. Venture Capitalists have been an important part of this trend (companies that are or were once VC backed account for 11% of the US workforce and over 20 of US GDP).

The sky is not falling and the day after the tax code is changed (if we’re not successful in convincing lawmakers what a bad idea this is), little will be different in my job or in the jobs of most investors (although no doubt the lawyers will be hard at work figuring out new investment structures). But there is no doubt in my mind that this massive alteration in how we tax the work of a group of people who nurture and fund innovation in the US will radically change the long term trajectory of the our country’s innovation economy. With the focus on job growth and job creation and with countries like China and India knocking at our door trying to be the growth engines for the next millennium’s global economy, is now the time to put shackles around the building blocks of what’s allowed the US to lead the world in technological innovation? I, for one, surely don’t think so.

I’m getting sick of the bullshit

I love the start-up world. I love working with founders and young companies. I love the excitement of working on business ideas that are new and different. I love seeing the success that often comes from this hard work. I’ve never before in my professional life seen a time of such innovation and creativity. At Foundry we see more business plans now than we ever have. And what’s more, more of those business plans are really interesting (and fundable).

It goes without saying that I love the business of venture capital. I love helping entrepreneurs work on their ideas. And I love helping companies figure out how to become as successful as possible. I love the challenge of trying to figure out the next great investment and the energy that comes from working with amazing and creative people.

But I’m worried and I wanted to get it out there.

I’m worried that in all the hype, in all the “we launched our company” events, and “we changed our name again” parties, and “we redid our website – come celebrate!” shindigs, and the SXSW parties, and the hoodies, and everyone who is “killing it!”, that we’re losing sight a bit of the really hard work that is creating and building a business.

I’m worried that in offering term sheets after a single 60 minute meeting, and in pricing early stage deals like they were already late stage successes and most egregiously by constantly running around self promoting and self aggrandizing, VCs are falling prey to a cult of personality about themselves and forgetting that their jobs are to help companies be successful. And as far as I can tell, very few seem to believe what I hold as a fundamental tenet of the venture industry, which is that entrepreneurs come first, not VCs.

Don’t get me wrong. I enjoy a good party (not to mention a good hoodie!). And I recognize the reasons to celebrate important company milestones and in going to industry events like CES and SXSW. And in bringing a bunch of customers, prospects and partners together at a social event. But I feel like I’m hearing less of “did you see XYX company’s great new product” and more “are you going to so and so’s party at ad:tech:”. I’m not exaggerating when I tell you that I’ve received 30 invites to SXSW parties but not a single invite to a panel session at the conference. And when someone tells me that someone is “killing it” (a phrase I think I hear 10 times a day these days), more often than not they mean “doing the job they were hired for”.

I hear more and more stories about companies making a pitch to a VC and having an offer before they walk out of the room (entrepreneurs: do you really want to work with someone who puts so little thought into their investment process that they would do this?). And the way VCs talk about the companies they work with has clearly shifted to be substantially more VC centric (lots of use of “I” and taking credit for company success as something they themselves created rather than participated in or helped with). And, of course, much has been written about rising valuations and the potential risk this poses to particularly early stage companies. Not to mention the increasing popularity of the “party round” where many VCs participate but no one actually takes ownership (also not good for entrepreneurs, in my opinion).

And it feels like a lot of this is for external show. I’m cool; I run a shit hot start-up; I saw [insert big name technorati here] at our company party last night. I’m in such and such company with [long list of other investors] and doesn’t that make me awesome. I’m awesome I’m awesome – look at me!! And not really about building great products or great businesses.

So by all means, lets keep having fun. But let’s also remember that the goal is to build great companies. And please – my fellow venture capitalists – can we take it down a few notches and remember that our role is a supporting one. If you wanted to be the star you should have become an entrepreneur.

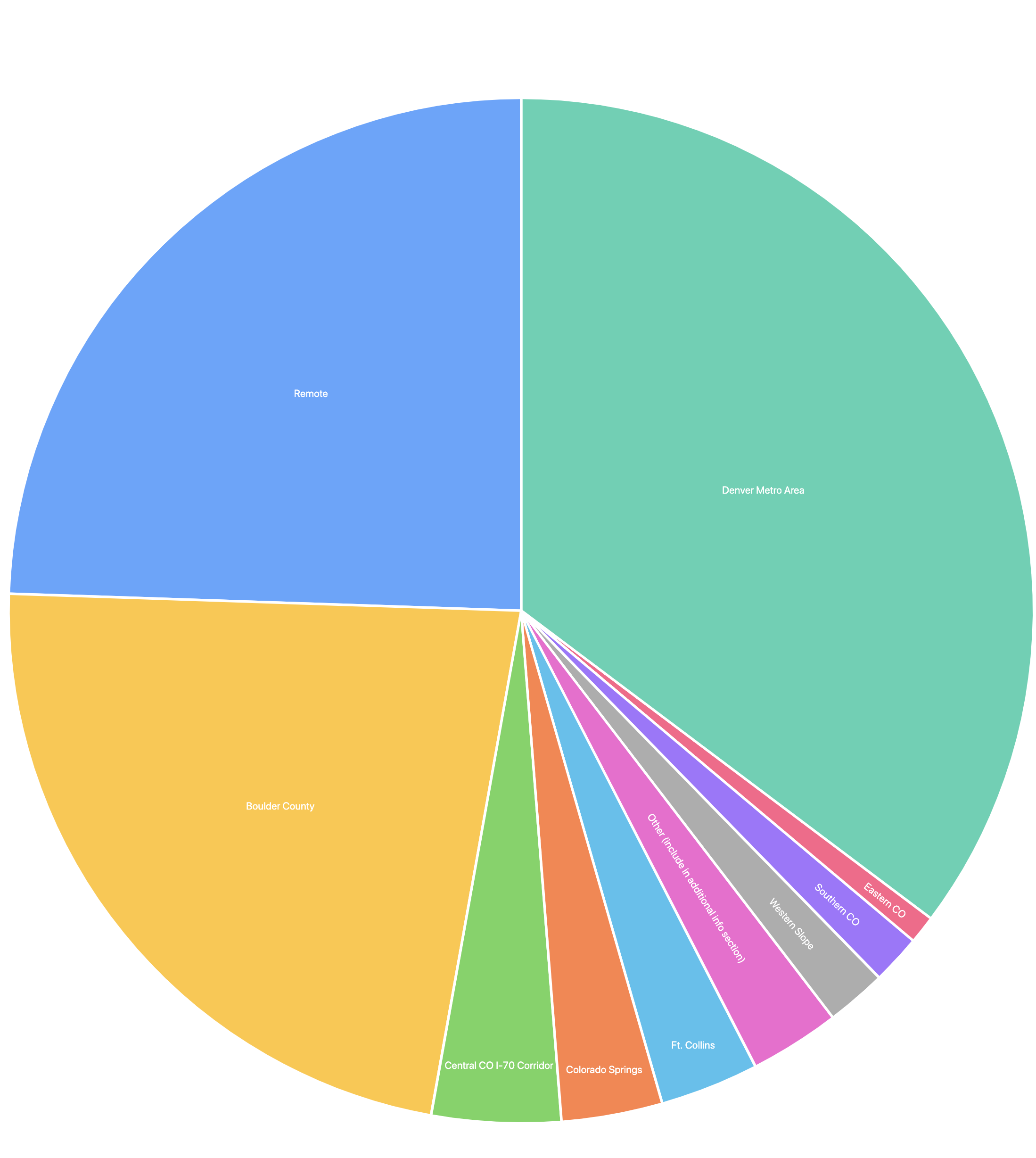

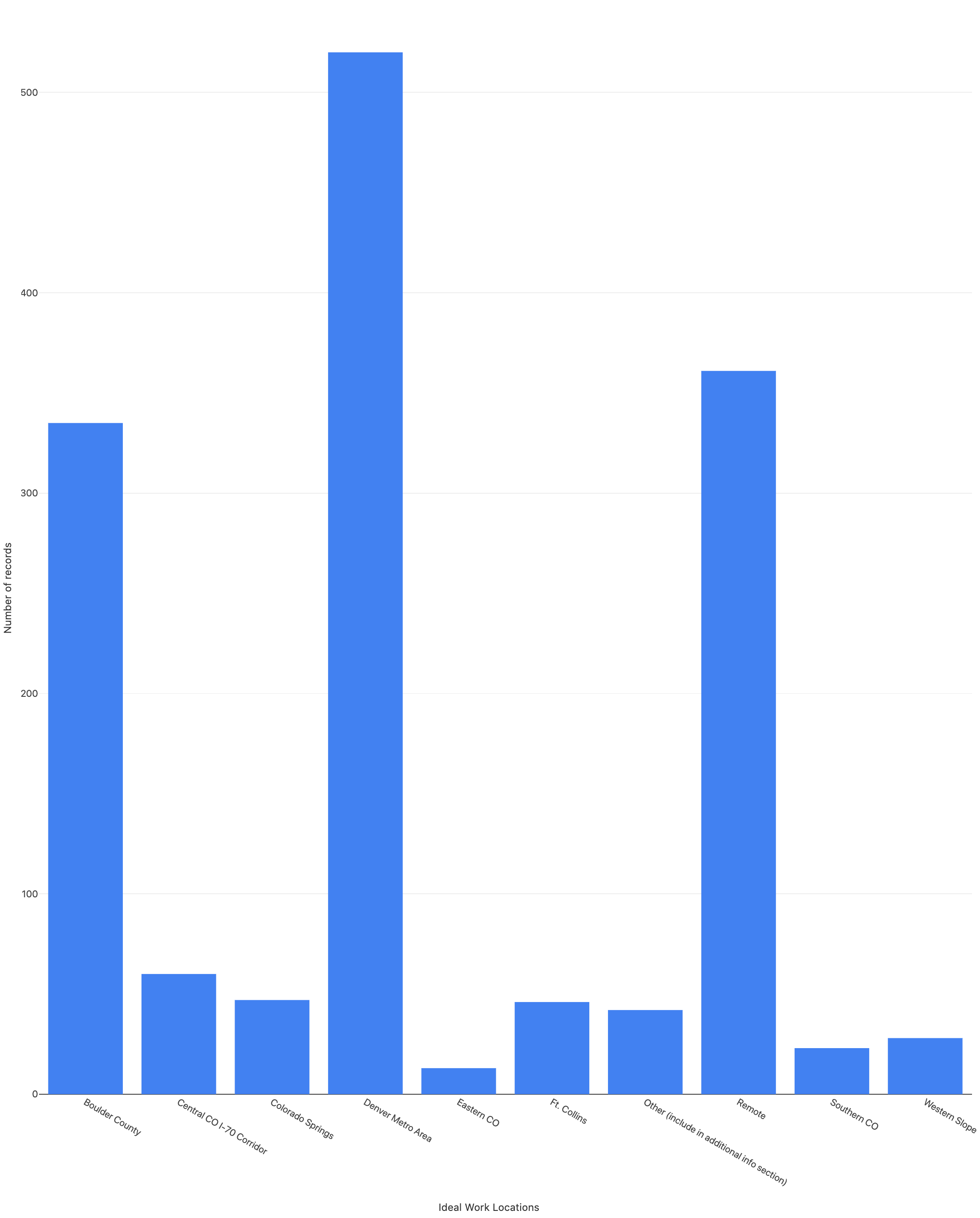

An Update on The Colorado Talent Network

Organizational Scaling

For the early part of your business you’re likely too busy to be spending a lot of time thinking about management structures, team optimization and how your business scales. You’re just getting shit done. And, even for experienced executives, making quite a few things up as you go along. The solution to many early scale challenges is to find something that works and then do more of it. That works great, right up to the point where it stops working completely. We’ve had a lot of companies go through scale challenges (I’d say typically around 100 people, but plenty of companies have muscled through that point and built 200 or even 300 person organizations without paying much attention to the scale structured needed to make that kind of organizational scale actually work. Here are a few things to think about/look out for based on our experience messing this up over and over again.

Don’t be the single point of failure. For good reason, CEOs often are the key decision maker early on in a business. You likely approve any major expenditure and certainly all new hires. As your business scales this doesn’t work. Maintaining control of expenditures in this way isn’t you being a thrifty CEO, it’s you creating a bottleneck for anything getting done and not empowering your team. Budgets and delegating and distributing authority (with clear limits and rules) is how this is better managed.

Matrix, don’t hub and spoke. While plenty of companies do some form of a management team/e-team meeting, many don’t in favor of 1:1 conversations with the CEO. This can sneak up on you as is often the product of an early team running around all over the place and often not in the same state or country, let alone the same room. So the CEO starts direct check-ins to make sure everyone is on the same page. Great. But that doesn’t scale and it doesn’t allow your scale VPs to work collaboratively on the business. An awesome off-site isn’t the remedy to this. Weekly meetings with everyone in the room – talking to each other, not just reporting back to you – is.

Your head of talent is a key manager and should report to the CEO. Gone are the days when HR reported to the CFO as a purely administrative function. Have a talent professional with a seat at the e-team table and have them report directly to you as CEO. That elevates the position properly in your organization, empowers them to be a driver in your business and will pay back dividends many times over in terms of reduced turn-over, greater transparency and alignment across the organization and fewer headaches for you as CEO.

Communicate. The larger you get the more more deliberate you should be about communicating across the organization. The company takes direction from you as CEO but it can’t read your mind. So communicate often and clearly with the entire team, not just your direct reports. One of my favorite examples of this is Scott Dorsey’s famous Friday Note. Scott led Exact Target from their founding to $2.5bn exit. Every Friday, no matter where he was in the world, he’d send a note to the company talking about what was going on with the business, what he was up to and sharing additional thoughts about the market or something interesting he was reading or thinking about. His employees loved it, it set the tone for the organization, and everyone know that they’d hear from the CEO directly every week. Not necessarily what you need to do, but find some way of communicating with everyone at the company on a regular basis.

Invest in systems. This one stands out – it can be hard to spend money internally when there’s so much [product/sales/marketing/etc] to do at your company. But growing past the startup stage can require an investment in some internal systems that help create alignment and facilitate the communication that I’m describing above. This comment goes beyond internal HR related systems and includes making sure that you’re not cheaping out on other systems that are critical to running your business (i.e., by limiting access to them to a small number of employees). Take a broad view of systems and make sure you’re not skimping out on the last 5% of cost that can drive outsized benefit.

Hopefully this has spurred some thinking about how to scale the management side of the business. I’d love to hear more ideas, so let me know what other things changed for you markedly when your company scaled past 100 or 150 people.

Board Diversity / Network Diversity

Fred Wilson’s recent post on diversity was thought-provoking on several levels and got me thinking not just about board composition but more broadly about the question of networks and how relying too heavily on existing networks can limit the diversity of those networks. There are many things that we (meaning the tech and venture industries, but I’m also shining this light on myself here) need to do to better promote and support equity and diversity in our work. To some extent at the core of this challenge is that many of us have limited diversity in our own personal and professional networks (see this interesting take from Rick Klau of Google on this topic). Fred’s post helped clarify one of the real challenges of limited networks because in large part the search for outside board members is an exercise about the network of one’s current board members’ networks. Companies typically look for new board directors on their own (meaning they typically don’t engage a search firm) and the result is that most new board member are either directly connected to their existing board or management team or one degree away. That’s incredibly limiting, even for a group (tech entrepreneurs and investors) that considers itself very networked.

Fred Wilson’s recent post on diversity was thought-provoking on several levels and got me thinking not just about board composition but more broadly about the question of networks and how relying too heavily on existing networks can limit the diversity of those networks. There are many things that we (meaning the tech and venture industries, but I’m also shining this light on myself here) need to do to better promote and support equity and diversity in our work. To some extent at the core of this challenge is that many of us have limited diversity in our own personal and professional networks (see this interesting take from Rick Klau of Google on this topic). Fred’s post helped clarify one of the real challenges of limited networks because in large part the search for outside board members is an exercise about the network of one’s current board members’ networks. Companies typically look for new board directors on their own (meaning they typically don’t engage a search firm) and the result is that most new board member are either directly connected to their existing board or management team or one degree away. That’s incredibly limiting, even for a group (tech entrepreneurs and investors) that considers itself very networked.

One of the things that’s really hit home with me over the past weeks as I’ve reflected on why I have done such a poor job promoting diversity across my work (and venture more broadly has) is that I/we need to do a better job of proactively building networks that include more diversity. I recognize that this is hard – it’s something that I’ve been consciously trying to do for years and I know from first hand experience that it takes both time and effort. On the board level, supporting organizations such as The Board List, himforher, and The Valiance Funding Network are good ways to jump-start the process. But conscious and deliberate effort is required to both recognize that many of us have limited networks when it comes to diversity and that we can do more to expand those networks. There’s a change in mindset that needs to accompany this and I’d encourage us to embrace it rather than ignore our network shortcomings or rationalize them away (there are tons of interesting people from all sorts of backgrounds out there – it actually doesn’t take that much work to find them and start connecting).

Fred also talks about the challenge of opening up new seats in the board room. The basic issue is absolutely correct – board rooms are too static. In economics, there’s a term known as business dynamism. Ian Hathaway and Robert E. Litan, in a report for the Brookings Institution describe business dynamism as “the process by which firms continually are born, fail, expand, and contract, as some jobs are created, others are destroyed, and others still are turned over.” Importantly they go on to note that “[r]esearch has firmly established that this dynamic process is vital to productivity and sustained economic growth.” Almost like a living organism, economies stay healthy by constantly building and changing. It’s a balancing act between growth and consolidating market power and new businesses and new ideas nipping at the heels of incumbents. The US has historically had relatively high dynamism and it is one of the factors that has been credited for America’s relative advantage in net job creation and the overall health of our economy.

Contrast this with the behavior of corporate boards which tend to be extremely and stubbornly static. They start with the founder and initial investors and typically when new investors come in, more investors are added to the board (rarely replacing an existing investor, more typically just adding to the number of people around the board table – for whatever reason, people are loathe to get off of boards once they’re on). We know from research that having more than three venture investors on your board is correlated with lower outcomes. Fred’s point in his post about creating board turnover is both helpful in terms of thinking about opening up spots for other diverse candidates but also in terms of enhancing the overall health of an organization by bringing in new ideas and new thinking. Bringing dynamism to the board level would be beneficial on both counts.

I took a look at this across my own boards (I’m on 14 company boards at the moment – subject for a different post about the optimal number of board seats…). My average tenure is over 5 years. I have several boards where I’ve been on the board for more than 10 years. Most of the board’s I’m on change their composition rarely outside of adding a new investor (I wasn’t able to quantify exactly but board’s I’m on add or remove a board member on average about every 4 years). It’s clearly a problem and one with both an easy solution (introduce more prescribed board turn-over) that’s at the same time very hard (a CEO I work with suggested this idea and when I volunteered to be the first person off the board was told that no, that wasn’t what they were thinking).

Still, I’d push us as an industry to think about how these two dynamics intersect. We know from studies that diversity at the management and board levels leads to better business outcomes. We know in other contexts, dynamism is helpful to systems. Perhaps we can and should bring those two ideas together.

Resume Coaching Resource

If you’re not familiar with Energize Colorado, I’d encourage you to check them out. Energize CO is a volunteer organization working to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 in Colorado. As part of this they just launched a pilot Resume Coaching program geared toward people whose jobs have been affected by COVID-19. This is a free resource utilizing volunteer recruiters from some of Colorado’s best companies and staffing agencies. If you’re interested in learning more, sign up here to schedule a resume coaching session. Energize Colorado is also offering help with business guidance, mental health, procuring PPE, and other resources to help Coloradans navigate the personal and professional hurdles of the pandemic (all listed on their website – check it out).

As a reminder, Foundry Group helped set up the Colorado #Covid-19 Talent Network for those looking for employment in the tech sector. If you’re a recruiter and looking to hire, please check out all of the great talent available on our portal. If you’ve lost your job or it’s been scaled back due to COVID-19, add yourself to the talent list. Job seekers can also view a list of Colorado companies who are currently hiring on this site.

Lastly, don’t forget that the COVID-19 Finance Assistant Network (FAN), a volunteer group of CFOs and other finance professionals that I helped set up, is available to small business owners who need help applying for government assistance, preserving cash, modeling and understanding the new realities of their business, and any number of other fiscal challenges due to the pandemic. The FAN is open to any small business owner in any geographic location (i.e., not just in Colorado).

This is a challenging time for so many of us but all of these resources are free so please make use of them if you need (and please let others know about what’s available). I love seeing Colorado coming together to support businesses and people that need help through this time.

Why I don’t sign NDAs

An entrepreneur started a meeting with me a few days ago by asking me to sign a non-disclosure agreement. I politely declined and thought I’d back that up with a post on the subject (I recall reading a few other VC blogger’s views on NDAs in past years – there’s certainly no lack of thought on the subject, although it does seem to consistently come up every year).

VC’s, as a general rule, won’t sign NDAs. No – we’re not trying to steal ideas from entrepreneurs or pass confidential information along. We’re just not in a position to review, negotiate and keep track of literally thousands of NDAs that would result if we started signing them on a regular basis. Here are a few specifics from my point of view:

VC’s have little but their reputation. I can think of few industries where individual reputation plays such a large and transparent role as it does in venture capital. As a VC, I have little more to trade on than the reputation I’ve built up with entrepreneurs, my investors, other VC’s, etc. Destroying this by sharing confidential information would just be plain stupid.

I can’t manage that many NDAs. It’s hard to imagine the challenge of managing a few thousand or a few tens of thousand of NDAs if we started signing them for every company meeting or business plan that we received. Even if I put them all on my own form (so that they were in theory all uniform in their requirements) it would be impossible to keep track of what information was presented and for what purpose.

I meet with competing companies. In the course of a year I see hundreds of business plans and take meetings with maybe 100 companies. In some cases these companies have similar ideas for products, are in similar markets or occasionally are direct competitors with one another. While I don’t trade information across companies, it could appear that way if I’ve met with two competitors or if one of the companies I’ve met with changes direction and starts to look like another company I met with at. I’d hate to get caught in the middle of a legal mess, exacerbated because I had NDAs in place with both companies.

I don’t know who my partners are meeting with. At Foundry, we tend to take a team approach to looking at deals and we have pretty advanced systems for tracking what deals we’re looking closely at. That said, I don’t know every company that my partners have reviewed a business plan for or have taken a meeting with. Not only can I not manage that many NDA’s from bullet 2, but as a firm, we can’t manage the added complexity of who has seen what from what company in what context.