Boulder is for Media

Recently Boulder based Datalogix announced that they had raised $25M to accelerate the build-out of its online ad targeting data business. The Datalogix story is one of perseverance and adaptation and it’s great to see them taking off. TechCrunch reported on the financing here. One thing caught my eye in the story and got my hackles up. In the very first paragraph about the financing Josh Constine said the following:

Since it’s based in Denver you don’t hear a lot about Datalogix, but the 250 employee startup is crucial to the future of advertising

Living in Boulder and being one of the more active adtech investors in the country (see our Adhesive investment theme) I can’t let this pass without responding. The Denver/Boulder market is actually a vibrant place for digital media companies. And you don’t have to look very hard to find them.

A few years ago Walter Knapp of Federated Media (who has a 70+ person office here after their acquisition of Lijit Networks in 2011) and I put together a conference called B.Media – a gathering of both local and national leaders working in digital media. And it was clear from that gathering that there’s no lack of energy around digital media companies here in Colorado (both on the technology side as well as the publisher side). From our early roots in ad serving with MatchLogic (acquired by Excite in ’98), and Crispin Porter + Bogusky’s 700+ person media agency headquartered here; SpotXchange which is doing pioneering work in RTB video; Yieldex (which was founded here in Boulder before moving their headquarters to New York); LinkSmart, a Foundry funded audience development network; Lijit which was mentioned above and built a very successful business here; Altitude Digital down in Denver; and Victors & Spoils which was recently bought by Havas.

I could go on, but I think you get the point. Denver/Boulder is a great place to start and build great digital media businesses.

Measuring customer satisfaction

There was a great thread this week on the Foundry CEO email list about Net Promoter Score and how companies are using it to measure the satisfaction of their customers (specifically in the case of NPS, their propensity to recommend the product or service to others). NPS can be a useful tool when used properly (which was much of the discussion on the email thread – who to measure, how often, etc.). But NPS can be cumbersome to measure, hard to understand granularly and not very helpful in letting you know what any given customer is really thinking about their interactions with your company (other than the extreme outliers).

There was a great thread this week on the Foundry CEO email list about Net Promoter Score and how companies are using it to measure the satisfaction of their customers (specifically in the case of NPS, their propensity to recommend the product or service to others). NPS can be a useful tool when used properly (which was much of the discussion on the email thread – who to measure, how often, etc.). But NPS can be cumbersome to measure, hard to understand granularly and not very helpful in letting you know what any given customer is really thinking about their interactions with your company (other than the extreme outliers).

The discussion and thinking about both the benefits and limitations of NPS got me thinking about a clever way that Trada measures customer satisfaction in their app on a customer by customer basis that I thought was worth passing along.

On most pages in the Trada app (Trada has a b-to-b focused application but this advice holds for b-to-c as well), there’s a small smiley face in the nav bar. It can exist in only one of four states – Happy, Meh…, Unhappy or Confused. It can only be set by the customer themselves (the admin login that the Trada customer service team uses doesn’t allow them to change the state) and customers are regularly prompted to update its status (which does not start “happy” so there’s no bias to just leaving it alone). It’s amazing how powerful such a simple idea has been for keeping tabs on how individual customers are feeling about their interactions with Trada and its application. It’s easy enough to use that customers engage with it. It can only exist in a limited number of states so it gets ride of the gravitation away from the edge that larger measurement scales tend to product, and is a great early sign to Trada’s customer service team that something is wrong with a client. The company uses data from this metric to reach out proactively to customers who are expressing confusion or dissatisfaction with their work on the platform. For Trada this doesn’t replace measuring NPS, which gives management a higher level view of overall customer satisfaction) but has been an extremely effective tool to help them deliver a fantastic customer experience.

Sometimes simple solutions can be very effective.

#3010: The Video

I blogged last year about the amazing 40th birthday trip my wife Greeley sent me and 9 friends on – cycling through Slovenia and Italy (original blog post along with a bunch of pictures here). We had a video put together of the whole experience that I thought I’d share.

Thanks to Mike Shum for the video production!

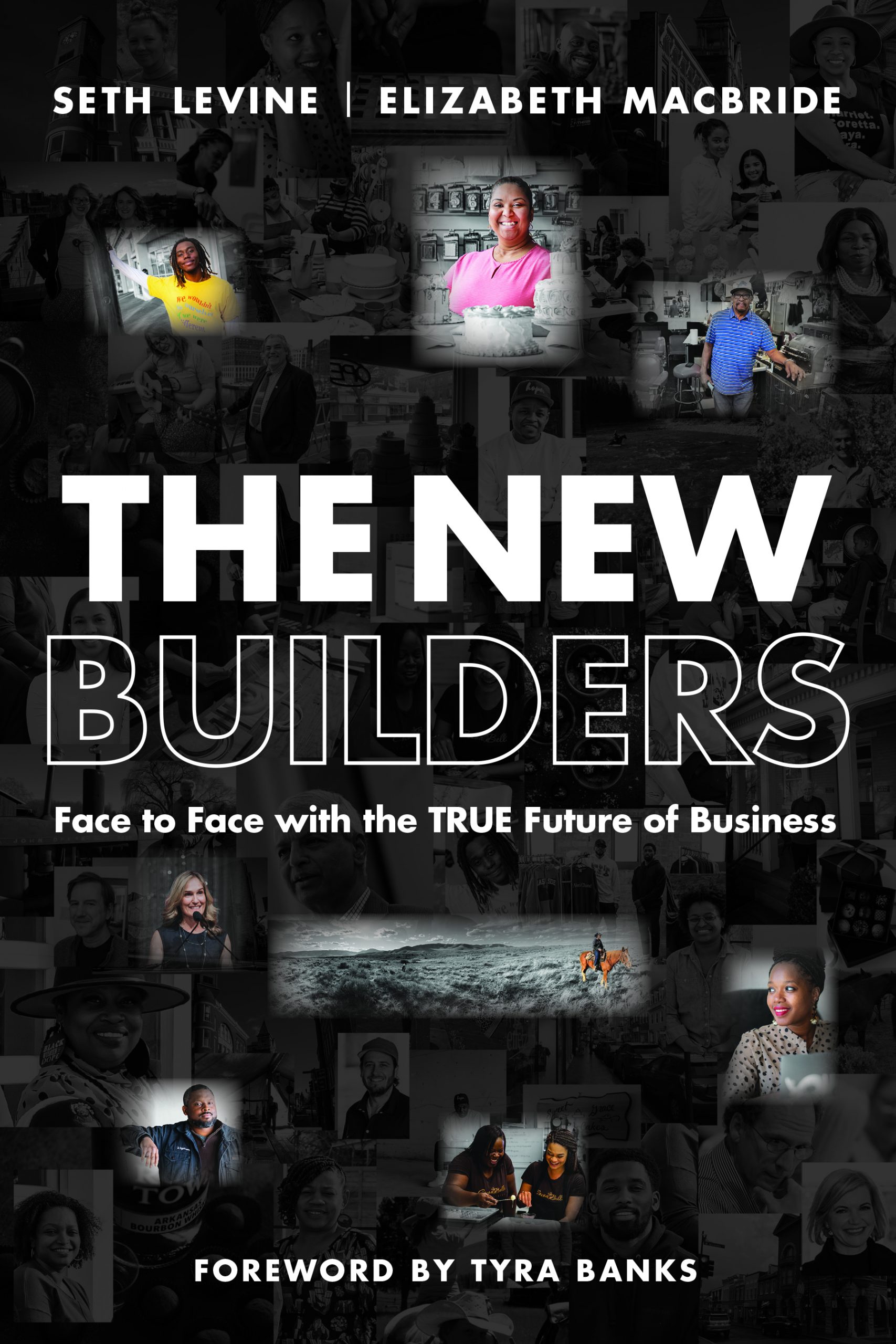

The Democratization of Entrepreneurship

One of the great trends we’ve been witnessing over the past decade, and in particular the past 5 years, has been what you might call the “democratization” of entrepreneurship”. It’s a powerful trend and one that I think will have a huge impact not just on the US economy and workforce, but perhaps even more intensely on other areas of the world – particularly developing economies.

There are several underlying factors that I think underpin this sift that are worth noting:

– The breaking down of geographic boundaries that confined entrepreneurial communities. Fundamentally entrepreneurial communities are networks (not hierarchies). And as such they thrive best in open environments that lack artificial restrictions. They also thrive best when information sharing is free and when entrepreneurs have access to other entrepreneurs (in this way entrepreneurial communities follow Metcalfe’s law of networks which states that the power of a network increases exponentially with the number of nodes on that network; entrepreneurial communities are exponentially stronger as they add more entrepreneurs to their “network”). The globalization of economies combined with the free flow of information fostered by the internet and other media has enabled entrepreneurs to establish connections that extend beyond traditional geographic boundaries and create virtual communities of peers where they once couldn’t exist.

– Entrepreneurship is becoming more highly valued. While many societies have thought of themselves as “entrepreneurial” it’s really only been in the past 10 years or so that entrepreneurs, as members of the creative class, have been truly celebrated. Where once striking out on one’s own was considered overly risky and either big companies (or in some countries state enterprise) was the path to job security and economic independence, now in many parts of the world entrepreneurship is embraced (think of the emphasis both candidates in the recent US election put on entrepreneurs as the growth engine of the US economy, for example). This acceptance (even celebration) of entrepreneurship is opening doors for many people around the world that were until recently closed due to cultural and economic pressures.

– Entrepreneurs don’t care about pedigree. I referenced above a belief that entrepreneurial communities are networks, not hierarchies. Openness, the free flow of information, the lack of community gatekeepers and entrepreneurs as leaders are hallmarks of these networks (vs. hierarchies which are closed, tend to have a small number of people who control access to the system and where information flow is controlled and limited). As a result the fundamental tenants that underpin these networks there is a decreased emphasis on pedigree, background and connections. While this hasn’t completely taken hold in all countries, in many places entrepreneurs are rightly judged by the strength of their ideas, the value they bring to the community and the success of their past efforts and not on their family name or where they attended school. This has opened the door for many entrepreneurs who 10 or 20 years ago would have found themselves cut off from the opportunities they have today.

– A focus on mentorship and giving first. One of the most powerful trends in support of the democratization of entrepreneurship has been the establishment of broad mentor networks that support entrepreneurial communities. These networks are aided by the trends noted above and stem from the fundamental belief that a larger and larger number of experienced entrepreneurs are embracing of giving first, getting later. Ultimately the best mentor relationships become two way but the going in expectation of the mentor needs to be that they’re participating first to give with no expectation of anything they’ll personally take away other than the satisfaction of helping out. The development of these mentor ecosystems – bolstered by the rise around the world of accelerator programs (the Unreasonable Institute being a great example) – has allowed entrepreneurs greater access to advice and counsel and I think helps create better entrepreneurs and more vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Fundamentally the world benefits from the democratization of entrepreneurship as more people look to themselves as the engine to grow beyond their circumstances. And importantly this phrase works in reverse as well – entrepreneurship promotes democratization. Entrepreneurs value the stable systems that democracy tends to bring, they see themselves and not government as the answer to their societies challenges, they provide jobs and economic stability that promote stable society and they work in networks that by their nature are fundamentally more democratic than hierarchical regimes. I don’t have a crystal ball and I don’t know exactly what the next 20 or 50 years will bring. But I do believe that the global trend towards entrepreneurship will continue and that the world will be much better for it.

Marc Barros on the shift from Product to Marketing/Sales

Marc Barros, the founder of Contour cameras wrote a great follow-up to my post on your company’s shift from a product focus to building out a sales and marketing organization that’s definitely worth reading. A few excerpts here:

1. Make A Clear Definition of Success

Early on, often before you raise venture capital, you want to create a clear picture of what the future looks like. That picture can include a range of things such as how you define your culture, values, employee morale, size, revenue growth, market domination, etc. Equally how you define success could range from world domination (e.g., Square) to building a small company focused on great products (e.g., 37 Signals).

Whatever the definition for success is, the best companies know this early on. They are already thinking about how they transition from their initial customers to growing the business. So when they do raise venture money they are clear about what the money is for and how they are going to use it to complete their ultimate vision.

At Contour we weren’t clear early on about what we wanted to be. At the core we were always focused on building great product, but along the way we didn’t shift our priorities from the best products to reaching more customers. We weren’t sure if we wanted to lead the market, follow the market, just make the best products, be a niche brand, etc. Instead we invested a little bit everywhere, never recognizing when we should shift from satisfying our early customers to a focus on how to reach a lot more of them.

2. Every Company is Building a Brand

Just because you are a product-focused or technology-focused company doesn’t mean that you aren’t building a brand. You are.

No different than Apple, your brand matters. The name, what it stands for, what it feels like, even what it smells like. Some of the best technology companies have built the stickiest brands. Look no further than Google, who through Marissa, was obsessed with its brand. I’m sure there was a lot of tension within Google about what was considered on brand, regardless she was consistent in protecting its image. Another great example is Intel. Technology at its core, they spend serious dollars to brand “powered by Intel” at a consumer level to make no doubt consumers wanted their technology.

If you recognize early on you are building a brand, it helps to lift your head up above the product/technology and begin thinking about how you are going to scale your platform.

3. Don’t Divide Your Organization

A traditional way to see the world is to divide the company between the functions: sales, marketing, product, finance, operations, etc. This is consistent with how we are taught to run a company and with how people view their roles within the organization. This is even consistent with how Seth phrased it, shifting from product to sales/marketing. I have come to believe it’s the wrong way to lead a company, especially early on.

It’s true your company will have specialists that can handle customer relationships, design things, write code, etc. But it doesn’t mean all of these people have to be working on different objectives.

If we remove the functional titles for a minute and talk about what the company is trying to accomplish it becomes much clearer. Early on you are finding your customer and building a product to satisfy them. As Seth says you are constantly cycling between customer feedback, improving the product, and getting more feedback. This process can sometimes take years until you have built a great product that your customer can’t stop using with a business model you think is sustainable. To do this well you often hire designers, engineers, and product managers. Before you know it your team is great at understanding the customer need and building a product.

Skipping forward you decide you want to really “grow” the business. If we forget the traditional functions of “sales/marketing,” and rephrase the objective, we’d say the goal is to get more customers. The more customers, the more revenue, and hopefully the greater the profits. There are a variety of ways you can grow your customer base. Getting new customers could be through adding new features (product), hiring people, traditional marketing efforts (social, advertising, SEM, etc), or even traditional sales efforts (sales teams, distributors, affiliates, new channels, etc). The important shift here isn’t the shift in hiring more sales people or more marketing people, it’s the shift to recognizing the most important thing is to get more customers. If the whole organization is thinking about this, including engineers, I bet you would come up with a variety of ideas and priorities to meet this. And instead of just the sales guys thinking about sales, you involve the whole team.

I believe the best companies focus the whole organization on a few priorities and therefore get the mind share of every employee towards the same goal.

Lastly, don’t rule out the need to shift the mix of your team mix, especially if your business isn’t generating enough cash flow to support the people you hired and your new growth objectives. At least by making these changes it would be clear to the whole organization that you are focused on growing your customer base.

The #hash economy

Back in the late 90’s I started noticing URLs at the end of many TV advertisements. They started as general company URLs (and were relatively infrequent) and eventually because almost ubiquitous leading not just to company home pages but eventually to product pages or other ares of a company’s site were one could get more information about whatever was being hocked on TV (or in a magazine, etc.). Fast forward a few years and we saw the same phenomenon with brands and their Facebook pages. And then Twitter. These were/are great ways for brands to get more information to people interested in their products. And to some extent through Twitter and Facebook “engage” with people so inclined to interact in that way with the producers of products they like and use.

Back in the late 90’s I started noticing URLs at the end of many TV advertisements. They started as general company URLs (and were relatively infrequent) and eventually because almost ubiquitous leading not just to company home pages but eventually to product pages or other ares of a company’s site were one could get more information about whatever was being hocked on TV (or in a magazine, etc.). Fast forward a few years and we saw the same phenomenon with brands and their Facebook pages. And then Twitter. These were/are great ways for brands to get more information to people interested in their products. And to some extent through Twitter and Facebook “engage” with people so inclined to interact in that way with the producers of products they like and use.

Now we’re seeing something pretty different and I’m interested to see where it goes (and have been thinking from an investment perspective for ways to participate in it as a growing trend). What I’m referring to (which will be obvious to anyone who read the title of this post) is the emergence of the #hashtag. You see it everywhere now. And not just on advertisements, but anywhere people are trying to drive a group conversation – at the end of magazine articles, during TV shows, sporting events, cable new channels. The #hash’s are generally topic related, not brand related (CNN isn’t pushing the #CNN hash but instead pushing #Election2012; we’ll all be tweeting about #superbowl this Sunday, etc.).

And like a lot of things in this new era of the internet the #hash economy is much more democratic. No one “owns” a #hashtag and the conversation is both easy to follow and easy to participate in (for example not limited just to one social platform). I think this kind of democratization of the internet is really interesting to follow. We’ve moved from platforms for people to broadcast out, to one where people could self organize into communities (but where these communities were still somewhat siloed) to one where we’re creating horizontal overlays to the internet that allow for much broader dissemination of information and that support more free flowing communities of interest (where both the participants in the community are free flowing but also the communities themselves).

I’m not entirely sure where this will take us, but I love the notion that barriers to participation are falling and as a result more and more people are able to interact and create content. The bar for that participation has been lowered massively and the old 80/19/1 paradigm (80% passive consumers/19% responders/ 1% creators of content) has been completely flipped on its head. I’d love your thoughts on this subject as it’s been knocking around in my head for a while but I’m not sure I’ve reached any definitive conclusions about where this is heading and what that means.

Shifting from a product company to a sales/marketing company

At the risk of overgeneralizing (although to be fair as a VC that’s pretty much my job description) and understanding that there’s plenty of grey area here, I’ve really been noticing recently just how challenging it can be for organizations to move from being product focused to sales and marketing focused. It seems worthy of a post (and hopefully getting some feedback on).

At the risk of overgeneralizing (although to be fair as a VC that’s pretty much my job description) and understanding that there’s plenty of grey area here, I’ve really been noticing recently just how challenging it can be for organizations to move from being product focused to sales and marketing focused. It seems worthy of a post (and hopefully getting some feedback on).

Early on in their lives most companies are built around a focus on product. They tend to be engineering heavy, key deliverables center around feature releases and sticking to a dev schedule and success is measured by the progress a business makes on building and releasing product vs. revenue generated from that product.

Then, at some point in an organization’s life this focus starts to shift. It generally starts slowly. Perhaps a sales person or community manager/user advocate is hired. Sales and usage related goals start to show up more prominently in weekly reports. You start thinking about marketing and outreach. Eventually you realize that you’ve fundamentally shifted the focus of the organization from one that existed to build product and get early usage to one that is focused on scaling that early usage and showing that you have a customer/user acquisition model that actually works. It’s not that product goes away or that the product is somehow “done” (all great companies are intensely focused on product in my experience) but that almost complete emphasis that you had on product from the early days is replaced by a true emphasis on customers.

This can be a challenging time for an organization. For starters many CEOs of tech companies are product people. And frankly it’s easier to map out a product roadmap of success (delivery dates, feature completion, etc.) than it is to live in the more spurious world of early customer adoption and sales. I think companies that make this transition most successfully embrace this shift completely. They acknowledge it within their organization. They set clearly defined goals and report openly whether they are meeting them or not. They develop strong feedback loops between sales and engineering to ensure that the future product roadmap reflects the reality on the ground. They measure everything they do on the sales and marketing side to learn what is working and what is not. And, of course, they treat their early sales process just like they did their early product development – getting as much feedback from the market as possible and quickly shifting course (the equivalent of reprioritizing a feature or shifting a design principal) if something’s not working.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this transition as we have a number of companies in the Foundry portfolio going through this metamorphosis right now.

That new era of Venture Capital is here

A couple of years ago I posted about what I thought would be the “new era of Venture Capital.” Specifically I was predicting that we’d see a strong barbell effect in VC fundraising. From that post:

I believe what we’re going to see in the venture industry is a bifurcation of fundraising– basically a barbell on the graph of fund sizes. Large, well known, multi-sector and multi-stage “mega-funds” will be able to raise $750MM or greater at one end of the scale, and smaller, more focused funds will raise $250MM or less on the other end – with a relatively small number of funds in the middle. [note: not sure what the problem is with the graphic from the original post, but I do know that it’s not rendering correctly)

Today the NVCA and Thomson Reuters released the Q4 and Year End 2012 fundraising statistics and they show this barbell in full effect. Mark Heesen of the NVCA put up a post on the NVCA blog that describes this:

Venture capital fundraising activity is being driven at two ends of the spectrum: Large funds – over $700 million – are being raised and deployed by well established firms who are stage agnostic (seed to growth equity), nationally and internationally driven, and have the exit track record to attract limited partners. … At the other end of the spectrum are the smaller industry or geographically focused funds that are largely looking at seed and early stage investments.

Overall we’ve seen somewhat of a rightsizing of the venture industry with a smaller number of firms raising money and fewer firms actively investing – a trend that has been long anticipated but that we’ve only really been seeing in earnest in the last few years. Of course with a large number of small, seed focused funds out there, the chances of getting “stuck” at Series A or B without a good funding option goes up (this is the so-called Series A crunch that we’ve been hearing about of late). That said, I’m a capitalist at heart (and by title) and believe that ultimately the market sorts these sorts of things out (coming your way in 2014: the Series A roll-up fund!).

Welcome Costanoa

While the world may not need more venture capitalists, it definitely needs more good ones. Enter Costanoa Venture Capital – launched today by long time investor and entrepreneur (and friend) Greg Sands.

As an entrepreneur, Greg is probably most famous for having named Netscape – literally, he was the guy who came up with that name. And of course, working there for quite a while in the seminal days of the internet. As a VC, Greg has been a long time partner at Sutter Hill Ventures.

I’ve had the pleasure of working with Greg on a number of investments over the years, including both LinkSmart and isocket in the current Foundry Group portfolio (these are both Costanoa investments). He’s a thoughtful and extremely helpful co-investor and board member. I love working with him.

And so it’s very exciting to see that he’s hung up a shingle and started his own firm. Because the world does need more good investors.

As a side note, and in the interest of full disclosure, my wife and I are investors in Costanoa. That’s a pretty good endorsement!

Some thoughts on your ABBA round

I’ve noticed an ongoing trend over the past year or so that’s worth highlighting and commenting on. As valuations have risen (become “frothy” in VC speak, which is our nice way of saying “too high”) companies have started raising much larger Series A rounds. This is anecdotal – I’ll try to validate it when the numbers are released – but where companies used to raise $3-$5M for their Series A, one response to higher valuations has been a much larger number of companies raising larger and larger Series A rounds (say $6M-$10M). I think this is driven both by entrepreneurs who want to take risk out of their business with more cash on the balance sheet, as well as by investors who, despite higher frothy valuations, are looking to hit certain ownership thresholds. The obvious result of this is much higher post money valuations of Series A companies which puts more pressure on the exit dynamic (ownership thresholds may still be achieved, but the threshold for the proverbial 10x has gone way up).

But that’s not what I want to talk about. I want to talk about your cash burn.

You already know that I believe that you’re burning too much money. This is an especially slippery slope when you have $7M or $10M on your balance sheet. Traditionally companies raised enough money in their Series A to last 12-18 months. And there’s a temptation with that much cash on your balance sheet to up your cash spend. Maybe significantly. But I think think this is a mistake. The right cash burn for your business is dependent on your stage, the opportunity in front of you and your ability to manage scale, more than it is a function of the cash on your balance sheet (obviously cash can’t be ignored, but having more cash in the bank doesn’t equate to a license to spend money more rapidly). Think of your larger Series A as really an A/B round together (or at least A and part of B). And spend accordingly. I counsel entrepreneurs who have raised a larger A round to act like they still raised the typical $3-$5m. Set burn appropriately and look for specific product and market milestones to increase cash burn, just as they would if they had raised less cash. Ultimately this takes advantage of the larger raise. Because in my experience, in the early stage of a business, spending more money generally doesn’t equate with a higher degree of likelihood of success (nor often true speed to market).